The Word Snoop (2 page)

Authors: Ursula Dubosarsky

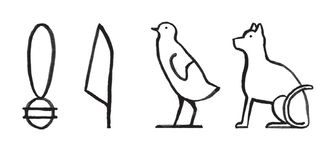

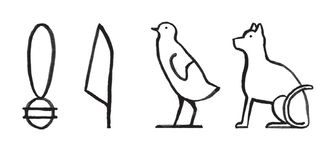

In ancient Egypt they did something a bit different. They carved or drew little pictures to show sounds or ideas. This kind of writing is called hieroglyphs, which means “holy writing” because it was mostly used by priests. Here’s an example of a hieroglyph:

Can you guess what the word means? (I’ll give you a hint—look at the very last picture. Meow!)

But neither cuneiform nor hieroglyphs were really alphabets. In an alphabet like ours, the signs or letters are supposed to stand only for sounds. To write the word

cat,

we use three letters to show those three sounds:

c a t

. But in writing systems like cuneiform and hieroglyphs, only some of the signs stood for sounds, while others stood for ideas or whole words, and sometimes these were combined (like the word for cat above—the first three pictures stand for sounds, while the last picture sums up the whole word). That sort of writing is a lot more complicated to write and to remember than an alphabet—in cuneiform alone there were about 1,500 different combinations!

cat,

we use three letters to show those three sounds:

c a t

. But in writing systems like cuneiform and hieroglyphs, only some of the signs stood for sounds, while others stood for ideas or whole words, and sometimes these were combined (like the word for cat above—the first three pictures stand for sounds, while the last picture sums up the whole word). That sort of writing is a lot more complicated to write and to remember than an alphabet—in cuneiform alone there were about 1,500 different combinations!

The Phoenicians, who lived north of Egypt as far up as modern-day Lebanon and Syria, are said to be the first people who used an actual alphabet. It looked like this:

The first two letters of the Phoenician alphabet were called “aleph” and “beth.” (Get it? Aleph-beth—Alphabet!) There were 22 letters, all consonants. Ys, thts rght, jst cnsnnts . . . The first letter, aleph, was not actually an A as we know it, but a funny sort of glugging sound in the throat. (Okay, you can stop glugging now.)

Anyway, because it made life simpler and writing quicker and easier, the Phoenician alphabet started to catch on, glug and all. The ancient Hebrew alphabet that most of the Bible was first written in is based on the Phoenician alphabet. The ancient Greeks adopted it too, adding extra letters for the vowels in around 1000 BC. (Phw! Tht ws lcky!) This is what the Greek alphabet looked like:

This alphabet eventually turned into the alphabet for Russian, Bulgarian, and other languages in that part of the world. In Italy, though, the Greek alphabet was adapted by the Etruscans, an amazing ancient people who lived in Italy before even the Romans did. This is how the Etruscans wrote their letters. (Are some of these starting to look familiar?)

The Romans got hold of the Etruscan alphabet, changed it a bit, and used it to write their language, Latin. It’s more or less this Roman alphabet that we use to write English today—and French and Spanish and Italian and lots and lots of other languages as well. In fact, the Roman alphabet is now the most widely used alphabet in the world. Have you ever looked at the names of the fonts on your computer? One of the most popular fonts is called Roman—and now you know why!

So you thought kindergarten was hard . . .

It probably took you a while to learn the 26 letters of the alphabet back when you started school. But actually, you should count yourself lucky. Some languages use alphabets with many more letters than that. Russian, for example, has 33 letters, and the Khmer language of Cambodia has over 70. And in China and Japan, where they write with signs called characters, there are hundreds, even thousands of different shapes to remember. Japanese primary school children are expected to learn about a thousand characters before they can go on to high school!

Okay. But why do we use a Roman alphabet for writing in English? Why don’t we have an English alphabet? Well, that’s exactly what the Word Snoop wondered too, so I waited until it was dark, and then I crept down a few hallways to do some snooping . . .

The English AlphabetO

ne of the first things I discovered is that English, as far as languages go, is not actually very old. It only began about 1,500 years ago (just a baby!). English began in a country called—you guessed it—England.

ne of the first things I discovered is that English, as far as languages go, is not actually very old. It only began about 1,500 years ago (just a baby!). English began in a country called—you guessed it—England.

England is part of the islands known as Britain, which are just northwest of Europe. In the beginning, before English was even thought of, the local people in England and the surrounding countries of Scotland, Wales, and Ireland mostly spoke Celtic languages, which are completely different from English. But then, in about the fifth century AD, some noisy tribes from Germany paid England a visit. Quite a long visit, actually, and they brought their own language with them. (At least they remembered to bring something!)

Some of these Germans were called Saxons, some were called Jutes and others Angles, which is where the word

English

eventually came from (think “angle-ish”). The German language they brought along is known as “Anglo-Saxon” or “Old English.” But not only did they bring their own language, they remembered to pack their own alphabet as well. (Who would travel without one?) This alphabet was called runes and is what early Old English is written in. Have a look and see what you think:

English

eventually came from (think “angle-ish”). The German language they brought along is known as “Anglo-Saxon” or “Old English.” But not only did they bring their own language, they remembered to pack their own alphabet as well. (Who would travel without one?) This alphabet was called runes and is what early Old English is written in. Have a look and see what you think:

So why don’t we use runes to write English? Well, the Germans weren’t the only ones to come and live in England. A whole lot of Christian monks from Europe and Ireland also turned up. They mainly spoke and wrote in Latin, using the Roman alphabet. After a while, naturally enough, they began to speak Anglo-Saxon/Old English too, but they wrote it in the Roman alphabet because it was easier for them than remembering all those runes. They did keep a few of the runic letters for a while, though, with lovely names like Eth, Thorn, Yogh, and Wynn. (Hmm, they sound a bit like some of the Word Snoop’s relatives . . .)

So for a while Old English was written in a mixed-up Roman-and-runic sort of alphabet. When the Vikings turned up in the ninth and tenth centuries, the Old Norse they spoke used runes as well. But the monks, who did most of the writing, preferred to use the Roman alphabet to write Old English. Finally, William the Conqueror came across the sea from France in 1066 and conquered everyone. He and his fellow conquerors spoke and wrote in French, which also used the Roman alphabet. Those runes didn’t stand a chance!

By the sixteenth century the English alphabet had more or less become the one we use today, with a few extra letters thrown in that the Romans didn’t have, like J, V, and W. Admittedly Thorn (remember him?) was still hanging around, although by this time it looked like the letter Y. That’s why if you ever get to see a book printed around that time, the word

the

is often written “ye.” (Thorn stood for the sound

th.

) But as time passed, even Thorn finally withered away and we were left with the alphabet we use in English now.

the

is often written “ye.” (Thorn stood for the sound

th.

) But as time passed, even Thorn finally withered away and we were left with the alphabet we use in English now.

Phew! That was a lot of snooping! I’m worn out, aren’t you? Although I suppose it did take thousands of years to make our alphabet, so it was bound to be a long story. And probably it will go on changing as even more thousands of years pass. Just imagine what it might look like in the year AD 4000 . . .

Let’s Change the AlphabetIt’s a sad thing, but not everybody who writes in English loves the Roman alphabet. (Sob!)

The main complaint is that the Roman alphabet was really meant to write the sounds of Latin words, not English ones. In English, there are at least 40 different sounds, and yet the Roman alphabet (even with the extras thrown in, like J, V, and W) has only 26 letters. It’s not surprising that all sorts of funny mixtures of letters have been used to create the sounds. But this has meant we’ve ended up with some pretty strange spelling rules (as I’m sure you would have noticed!).

Most of us think,

Oh well, that’s the way it goes, better learn my spelling list (sigh) and be done with it . . .

But the Word Snoop has discovered that some people have more adventurous minds. The famous American thinker Benjamin Franklin, for one. He had ideas about all sorts of things, including the English language. Way back in 1779, he said we should change the alphabet to make spelling more sensible. He suggested kicking out C, J, Q, W, X, and Y, and replacing them with six new letters, including a special one for the sound

ng

.

Oh well, that’s the way it goes, better learn my spelling list (sigh) and be done with it . . .

But the Word Snoop has discovered that some people have more adventurous minds. The famous American thinker Benjamin Franklin, for one. He had ideas about all sorts of things, including the English language. Way back in 1779, he said we should change the alphabet to make spelling more sensible. He suggested kicking out C, J, Q, W, X, and Y, and replacing them with six new letters, including a special one for the sound

ng

.

Ten years later in 1789, another American, the dictionary maker Noah Webster, had a different idea. He thought we should put little lines or dots above the letters, like they have in French and German, to show the different sounds. Then in the nineteenth century yet another American, the Mormon leader Brigham Young, suggested a whole new alphabet called Deseret that would make reading easier. Fifty years after that, the novelist Mark Twain, who wrote

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,

added his complaints about our alphabet. He said, “It doesn’t know how to spell, and can’t be taught.” (Tsk tsk,

bad

alphabet!)

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,

added his complaints about our alphabet. He said, “It doesn’t know how to spell, and can’t be taught.” (Tsk tsk,

bad

alphabet!)

Other books

Will You Remember Me? by Amanda Prowse

DarkWalker by John Urbancik

BirthControl by Sydney Addae

Codebreakers Victory by Hervie Haufler

Hunt Me by Shiloh Walker

Man Overboard by Monica Dickens

Eternal Flame by Cynthia Eden

The Law of Desire by Gwyneth Bolton

Silence Of The Hams by Jill Churchill

If I Could Tell You by Lee-Jing Jing