The World of Caffeine (33 page)

Read The World of Caffeine Online

Authors: Bonnie K. Bealer Bennett Alan Weinberg

As the saga of caffeine in England continues today, coffee remains popular, and soft drinks have become an important part of the new mix, but tea continues to be England’s most important source of the drug. Consider that in America, the country of coffee bibbers, about half of all caffeine comes from coffee; in England, more than three-quarters of the caffeine consumed comes from tea. England and her cousins, Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand, constitute four of the twelve top tea-consuming

countries in the world per capita, and they are the only Western nations to make the list.

75

England makes, sells, serves, and consumes, imports, and exports tremendous quantities every year.

Like the queen and Buckingham Palace, the afternoon tea, although it has declined in importance among the natives since World War II, has become a major tourist profit center. Establishments such as the Ritz hotel and Fortnum and Masons department store serve afternoon tea in a sometimes hectic environment that would have seemed like a nightmare to its originators. Nevertheless, the aristocratic patina of the afternoon tea, an inheritance from generations of English ladies, from Queen Catherine, through Anne of Bedford, and one reminiscent of the upper-class connections of the Urasenke tea masters, remains to this day. An attempt to capture and trade off this patina is evident in four-star hotels throughout the world that serve afternoon tea daily in a quiet, decorous setting, presented by a discreet serving staff and accompanied by the finest tea service that the establishment can afford. There, twentieth-century ladies and sometimes gentlemen meet to inhale a breath of the atmosphere of elegance and tranquillity that have been associated with tea over the centuries.

the endless simmes

America and the Twentieth Century Do Caffeine

ZING! What a feeling

—Line from Coca-Cola jingle, 1960s

Captain John Smith, who founded the colony of Virginia at Jamestown in 1607, brought the earliest firsthand knowledge of coffee to North America and is sometimes credited with having been the first to bring the beans as well. Smith was familiar with coffee from having traveled through Turkey. Neither the passengers of the Mayflower in 1620 nor the first Dutch settlers of Manhattan in 1624 are recorded to have included any tea or coffee in their cargo. It is impossible to be sure if the Dutch introduced either into their colony of New Amsterdam or whether that distinction belongs to the British, who succeeded them in 1664 and renamed the settlement “New York.” In any case, by the time of the earliest printed reference to coffee drinking in America, which occurs in New York in 1668, the drink, brewed from roasted beans, sweetened with sugar, and spiced with cinnamon, was already in common use. Around this time coffee seems to have displaced beer as the favorite breakfast beverage, and chocolate is recorded to have arrived in small private shipments, primarily as a pharmaceutical. In 1683 William Penn, who probably introduced both coffee and tea into Philadelphia, recorded in his

Accounts

that he purchased coffee in New York for his year-old Pennsylvania settlement and complained of the price per pound of eighteen shillings nine pence. At this price, the beans required to make a cup of coffee would have cost more than a dinner at an “ordinary,” or informal eatery, of the time. In light of this expense, it is not surprising that, during these first days in the colonies, beer and ale remained the usual drinks at meals other than breakfast, and both tea and coffee were pricey luxuries, with tea the more common of the two, especially in domestic use.

Boston has an early and distinguished place in the American annals of caffeine. Even before any American coffeehouse had opened its doors, Dorothy Jones was granted the first known license to sell coffee in America, in Boston in 1670, though no one knows if she was a purveyor of “coffee powder,” the name for the ground roasted beans, or of the drink itself. It was also in Boston that the London Coffee House, the first coffeehouse in America, opened for business. It constitutes the earliest example in America of the now popular bookshop café, for it is reliably reported that “Benj. Harris sold books there in 1689,” the first year of its operation. Of course, the tradition of selling books in coffeehouses dates back to at least 1657 in London, and after their invention in the eighteenth century, newspapers were printed and sold from the coffeehouses in both England and the New World.

In 1696 the King’s Arms, the first coffeehouse in New York, was opened near Trinity Church by John Hutchins. Its yellow brick and wood structure, with rooftop seating and a splendid view of the city and bay, is supposed to have been standing in Holland when it was purchased, dismantled, and its parts transported to America, where it was reassembled.

The first coffeehouse in Philadelphia was opened by Samuel Carpenter around 1700 on the east side of Front Street, above Walnut Street. Because it remained the only such establishment in the city for some years, it was referred to in the old days simply as “Ye Coffee House.” The Coffee House was apparently used as a post office, to judge from this 1734 excerpt from Benjamin Franklin’s

Pennsylvania Gazette:

All persons who are indebted to Henry Flower, late postmaster of Pennsylvania, for Postage of Letters or otherwise, are desir’d to pay the same to him at the old Coffee House in Philadelphia.

1

Benjamin Franklin (1706–90), always alert to new business opportunities, sold coffee, running an advertisement claiming, “Very good coffee sold by the Printer.” Around 1750 William Bradford, another Philadelphia printer, opened his own London Coffee House, at the southwest corner of Second and Market Streets. It became a thriving center for merchants, mariners, and travelers, and was used as a market for horses, food, and slaves, the last of which were displayed on a platform in the street in front of the coffeehouse.

American coffeehouses, which continued the British coffeehouse traditions as “penny universities” and enhanced their feared and celebrated status as “seminaries of sedition,” soon opened in every colony. At first they were simply taverns serving ale, port, and Jamaican rum, as well as coffee. But soon these coffeehouses featured in American official civic life in ways that had been unknown even in England: Their “assembly rooms” became the sites of court trials and council meetings. The Green Dragon, a coffeehouse tavern and inn, established in 1697, which Daniel Webster called the “headquarters of the Revolution,” was frequented in the next century by Paul Revere, John Adams, James Otis, and other illustrious rebels, and remained open in Boston’s business center for 135 years. Throughout this time, the Green Dragon remained a center of activity, hosting from the first, “Red-coated British soldiers, colonial governors, bewigged crown officers, earls and dukes, citizens of high estate, plotting revolutionists of lesser degree, conspirators in the Boston Tea Party, patriots and generals of the Revolution.”

2

The Grand Lodge of Masons, under the leadership of the first grand master of Boston’s first Masonic group, convened there as well.

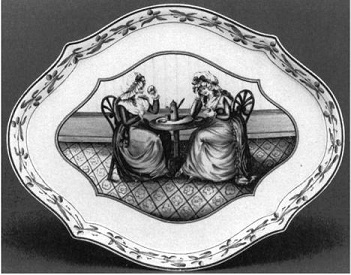

Colonial American tea tray with cartouch of ladies reading coffee grounds, illustrating the common practice of using grounds for divination, one similar to the practice of reading tea leaves that is more familiar today. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

It was in the Green Dragon that Revere and his co-conspirators are supposed to have met to plan the Boston Tea Party. The story of the Stamp Act of 1765, a British tea tax that turned Americans into some of the world’s most avid coffee drinkers, is well known. Tariffs and taxes frequently determined which of the caffeinated beverages, if any, were within reach of the average person, and had often been designed to do so. The opposition to the British tax prompted the Boston Tea Party of 1773, in which the British East India Company’s cargoes of tea were jettisoned into the harbor. From this moment in history, coffee became the favored caffeinated drink of Americans, indispensable at the breakfast table and the workplace ever after. The Bunch of Grapes, another of the earliest Boston coffeehouses, was the site of the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence.

New York’s Merchants Coffee House, at the intersection of Wall and Water streets, hosted the Sons of Liberty on April 18, 1774, who, following the example of their Boston compatriots, met there to plan their own blockage of British tea imports. The next month, leaders of the revolution gathered there to draft their call for the First Continental Congress. Neither was this coffeehouse forgotten in the aftermath of war and victory. For in 1789, New York City’s mayor and the state’s governor threw a lavish party there in honor of the election of George Washington.

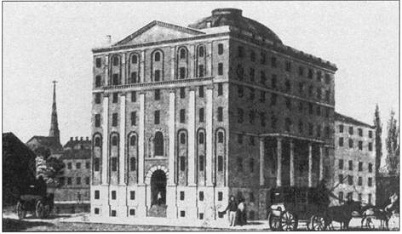

With the opening of the Exchange coffeehouse on Exchange Street in Boston in 1808, the institution reached a kind of acme. The Exchange was modeled after Lloyd’s of London and, like Lloyd’s, served as a center for ship brokers and mariners. Designed by Charles Bulfinch, the most celebrated American architect of the day, it stood seven stories high and was constructed of stone, marble, and brick, at a cost of half a million dollars. In 1817 the Exchange hosted a banquet for James Monroe, attended by John Adams and many other dignitaries. Probably the largest and most expensive coffee-house ever seen in the world, before or since, the Exchange burned down in 1818.

The Exchange Coffee House, Boston. This was the largest and most costly coffeehouse ever built. Erected in 1808, of stone, marble, and brick, it stood seven stories and cost $500,000. It was modeled after Lloyd’s of London, and was, like Lloyd’s, a center for patrons from the shipping business. (W.H.Ukers,

All about Coffee)

The early days of American coffeehouses were times of heavy alcohol drinking both in England and the colonies. The English “gin epidemic,” against which the College of Physicians had warned in 1726, asserting that it was a “growing evil which was, too often, a cause of weak, feeble, and distempered children,” continued unabated on both sides of the Atlantic. The revolution and the decades after marked a high level of alcohol use that exceeded any achieved in the twentieth century. In 1785, this widespread drunkenness prompted Benjamin Rush (1735–1814), a famous physician and reformer, to found an anti-alcohol movement, that, like many other such movements since, began by advocating temperance and later advocated abstinence. Rush was as fervent an advocate of the temperance beverages as he was an opponent of the alcoholic ones. His followers, who purchased tens of thousands of copies of his temperance booklets, helped to advance the cause of coffee, tea, and chocolate drinking in the new nation. Yet despite his efforts, around 1800 Americans still annually consumed about three times as much alcohol per person as they were to consume in the 1990s.

By the second half of the nineteenth century, America was consuming more coffee than any country in the world, and the drink had, in the minds of many of its inhabitants, come to be more identified with their pioneering, robust, democratic country than the stuffy, effete, class-stratified society of Europe. Coffee’s status in America is attested by Mark Twain (1835– 1910) in his travelogue

A Tramp Abroad,

in which he celebrates coffee, which he has obviously come to regard as quintessentially American, and recounts experiences with it abroad that many American travelers may find familiar today:

In Europe, coffee is an unknown beverage. You can get what the European hotel keeper thinks is coffee, but it resembles the real thing as hypocrisy resembles holiness. It is a feeble, characterless, uninspiring sort of stuff, and almost as undrinkable as if it had been made in an American hotel…. After a few months’ acquaintance with European “coffee,” one’s mind weakens, and his faith with it, and he begins to wonder if the rich beverage of home, with its clotted layer of yellow cream on top of it, is not a mere dream after all, and a thing which never existed.

In an 1892 entry in his

Autobiography,

Twain presents a somewhat more attractive picture of Italian tea drinking, which he observed while passing through Florence on the way to Germany:

Late in the afternoon friends come out from the city and drink tea in the open air, and tell what is happening in the world; and when the great sun sinks down upon Florence and the daily miracle begins, they hold their breaths and look. It is not a time for talk.

3

As the emergent capital of industry and the marketplace and the symbol of revolution and the mixing of peoples, America was the country best fitted to assume leadership in the twentieth-century saga of caffeine. However, if you ask a European visitor what, in his opinion, is the most noteworthy feature of American cafés, he is most likely, instead of mentioning complex ideological or social factors or the characteristic taste complexity of the American roast, to say, “They refill your cup without charge, even without asking!” American readers may wonder why this ordinary courtesy should be regarded as so important. But if you consider that many European coffee lovers and coffeehouse habitués spend hours nursing small cups that cost them twice as much as Americans pay, and that if they want another they must pay the full price again, you can see how, in the course of a life of café hopping, these refills could add up to a small fortune.

Perhaps the endless refill is symbolic of America’s special affection for coffee and of its general culture of largesse and informality as well. Coffee certainly plays the dominant part in the story of caffeine in the United States. Ever since their defiance of British tea taxes inspired the colonials to exchange the leaf for the bean as a patriotic duty, Americans cultivated a taste for coffee to the extent that they became by far the largest single national coffee importers on earth, and today they account for more than half of world coffee imports. Coffee is overwhelmingly the source of most of the caffeine consumed here.