The Worst Hard Time (20 page)

Read The Worst Hard Time Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

Most scientists did not take Bennett seriously. Some called him a crank. They blamed the withering of the Great Plains on weather, not on farming methods. Basic soil science was one thing but talking about the fragile web of life and slapping the face of natureâthis kind of early ecology had yet to find a wide audience. Sure, Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir had made conservation an American value at the dawn of the new century, but it was usually applied to brawny, scenic wonders: mountains, rivers, megaflora. And in 1933, a game biologist in Wisconsin, Aldo Leopold, had published an essay that said man was part of the big organic whole and should treat his place with special care. But that essay, "The Conservation Ethic," had yet to influence public policy. Raging dirt on a flat, ugly surface was not the focus of a poet's praise or a politician's call for restoration.

But one of the first things Franklin Roosevelt did was summon Bennett to the White House. Bennett said Americans in the nation's midsection had farmed too much, too fast. The land could not take that kind of assault. The greatest grassland in the world had been hammered and left without cover. The dusters that were just starting to make national news were not a work of God. And they would get worse. Well then, the president asked: was it possible to undo what man had done?

Bennett made no promises. He was forceful, he had charisma that Roosevelt liked, and he took to the taskâas director of a new agency within the Interior Department set up to stabilize the soilâwith relish. He had little money or staff. But Big Hugh was a showman and a scientist who knew his subject. If Roosevelt believed, as he said in his forgotten man speech, that the core problem of the Depression was that farmers and the small towns dependent on them had fallen completely out of the economy, Bennett was his intellectual soul mate as he looked at what caused the Great Plains to break down. He knew in his heart that something profound had occurred, that man had changed nature. The balance would have to be restored from the ground up. Bennett must get people to see the crisis in a different way, to accept some of the blame. It called for a period of shock therapy. By some estimates, more than eighty million acres in the southern plains were stripped of topsoil. A rich cover that had taken several thousand years to develop was disappearing day by day.

Big Hugh was only a few weeks into the job when he started with speeches that attributed the failed farm system to "a pattern of land use that was basically unsound." Millions of years of runoff from the Rocky Mountains had deposited a rich loam over the plains, held in place by grass. For that land to be restored, Bennett suggested, people should look back to the days before the plow broke the prairie. The answer was there in the land, in what had been obvious to XIT cowhands and Comanche Indians all along: it was the best place in the world for grass and for animals that ate grass. But could the native sod ever be put back in place, the balance restored? Or had they killed it forever?

The drought did not take a holiday. Weather forecasts took on a dreary similarity: dry, with dusters. The wind rumbled through and tore off great sheets of prairie soil. As storms darkened the skies, people started to believe they were being punished for something awful. When Roosevelt took a trip to the plains, a farmer in North Dakota held up a hand-painted sign: "

YOU GAVE US BEER. NOW GIVE US RAIN.

"

The president was not optimistic. "Beer was the easy part," he said.

T

HE LAND WOULD NOT DIE

an easy death. Fields were bare, scraped to hardpan in places, heaving in others. The skies carried soil from state to state. With no appreciable rain for two years, even deep wells were gasping to draw from the natural underground reservoir. One late winter day in 1933, a battalion of heavy clouds massed over No Man's Land. At midday, the sun disappeared. Lights were turned on in town in order to see. The clouds dumped layers of dust, one wave after the other, an aerial assault that covered streets in Boise City, buried brown pockets of grass, and rolled over big Will Crawford's dugout and the patch of ground where Sadie had tried to establish her garden with a tin-can irrigation system. They had to shovel furiously to avoid being swallowed by the enraged prairie.

Hazel Lucas Shaw watched the dust seep through the thinnest cracks in the walls of their rental house, spread over the china, into the bedroom, onto the sheets. When she woke in the morning, the only clean part of her pillow was the outline of her head. She taped all the windows and around the outer edge of doors, but the dust always found a way in. She learned never to set a dinner plate out until ready to eat, to cook with the pots covered, to leave no standing water out for long or it would turn to mud. She had decided to give up the teaching job that paid worthless scrip and to try and start a family. Her husband, Charles, had at last opened his business, a funeral home in the rental house. Town was supposed to be an easier place to

live than a dead homestead to the south. But Boise City faced the same tormenterâthe skies that brought no rain, only dirt. Some days Hazel put on her white gloves and sat at the tableâa small act of defiance that seemed both silly and brave.

The temperature fell more than seventy degrees in less than twenty-four hours one February day in 1933. It reached fourteen below zero in Boise City and still the dust blew in with the arctic chill. Hazel tried everything to stay warm and keep the house clean. Dust dominated life. Driving from Boise City to Dalhart, a journey ofbarely fifty miles, was like a trip out on the open seas in a small boat. The road was fine in parts, rutted and hard, but a few miles later it disappeared under waves of drifting dust. Unable to see more than a car length ahead, the Shaws followed telephone poles to get from one town to the next.

At the Panhandle A&M weather station, they recorded seventy days of severe dust storms in 1933. Weather forecasting was still a rough skill in that year, a hit and miss game. The basic instruments for measuring air movement, temperature, and all that fell from the sky were little changed over the previous 350 years. The government predicted the weather by rounding up readings from more than two hundred reporting stations across the country and from air balloons, planes, and kite stations. The information was sent by Teletype to Washington twice a day. There, a map was drawn up and a forecast went out from the weather bureau for different regions of the nation. It was based on the movement and struggle between high and low barometric pressureâan ancient way of predicting weather. The forecast always originated in the capital, which is one reason why older, more skeptical nesters still referred to weather prediction by its nineteenth-century termâthe "probability." A hardy homily such as "Clear moon, frost soon" or "Red sky at night, sheep herder's delight, red sky in the morning, sheep herder take warning" was more trusted, and not just by those who worked the land. During his days as an airmail carrier, Charles Lindbergh said he ignored the official weather bureau forecast; it was useless. Throughout the 1920s, as one technological marvel after the other changed American life, the tools of weather forecasting remained items that would have been familiar to

Benjamin Franklin. And there was a dire need for some sense of what tomorrow would bring, especially with the dawn of widespread air travel. When weather turned lethal without notice, it killed peopleâsometimes in large numbers. For tornadoes, there were no warnings at all. A big twister roared through the Midwest in 1925, killing 957 people. The weather bureau's only great achievement was taking accurate measurements: atmospheric pressure, days without rain, total precipitation, swings in temperature, and wind speed.

March and April 1933 were the worst months of the yearâa two-month block of steady wind throwing fine-grained dirt at the High Plains. The cold snap had killed what little wheat had been planted last fall. There was now an expanse of fallow, overturned land nearly half the size of England, no pasture for cattle, and no feed for other animals.

Fred Folkers spent most of his days shoveling dust. The shovel was his rescue tool; he never went anywhere without it. In a long day's blow, the drifts could pile four feet or more against fences clogged with tumbleweeds, which created dunes, which then sent dust off in other directions. He tried to modify the fences so dunes would move along, below the rails. Some mornings, Folkers did not recognize his land as the shifting dunes produced dust mounds with ripples holding the imprint of winds from overnight. Other mornings, his car was completely covered. And after he wiped his car clean, it was hell to start it, the dust clogging the carburetor.

He knew now he was probably going to lose the orchard, the last living thing on the Folkers farm. All the pails of water he'd hauled from the tank to the little grove of trees seemed for naught. His living memory patch of the old Missouri home, the peach and cherry trees, plum and apple, the gooseberry, currants, and huckleberryâthey could not live through the howling dirt of 1933.

At the end of April, with no green on the land and no rain from overhead, came a duster that lasted twenty hours. For most of the storm, the winds blew at better than forty miles an hour. The dust was strong and abrasive enough to scrape the paint off the Folkers house, to get into the digestive system of cattle.

"Here comes another roller!" was the shout in Boise City, a warning to take cover. People watched the horizon darken with the approach of the duster. There was no escape. They could not stay outside for fear of getting lost or of choking on a blast of gritty air. And while indoors offered protection from the wind, it was no respite from the fine granules.

Lindbergh, the greatest aviator of his day, flew into this corrosive air space on May 6 while trying to cross the Texas Panhandle. His plane choked, the engine sputtering, and bucked wildly in the turbulent currents. Six years earlier, Lindbergh had crossed the Atlantic, flying just barely above the ocean on his way to Paris. Now, he could not cross the flattest part of the United States. He made a forced landing in the part of Texas where a promoter had tried to plant a part of Norway. He was greeted by children as a god sent down from the heavens, with front-page headlines throughout the southern plains. Lindbergh wanted no part of it. He seemed spooked by the dusters. He slept in his plane, then flew out after a two-day delay.

One day in late May, just as the high wind season started to ebb, the dust disappeared, and out came the blue empty skies that had so enticed nesters in years past. But by midmorning, dark clouds were back. They looked like rain cloudsâan answer to everyone's prayers. Bigger, darker, heavier clouds were on top of themâdusters piggybacked on a system that would normally bring only rain. In the early evening, the skies broke, delivering hard brown globs of moistureârain and hail, which had picked up dust on the way down, falling as mud pellets. The dirty torrent smashed rooftops, buckled car hoods, made cows bawl in agony. More was on the way. A funnel cloud appeared.

"Twister!"

People raced for shelter, praying for deliverance. The tornado touched down in Liberal, Kansas, near the Oklahoma border, in the heart of tornado alley. It lifted roofs from barns, knocked down warehouse walls, pushed houses from their foundations. An old broomcorn factory was completely destroyed. Stores were pulverized into piles of sticks. Windows shattered. Downtown was reduced to a heap of timber and bricks. Four people were killed; nearly eight hundred were left without homes. And then not long after the tornado swept

through, destroying the heart of one of the bigger towns on the High Plains, the mud pellets came again, tossed from the sky, a final insult.

In the summer, winds knocked down telephone poles on the Texas Panhandle and shoved aside grain silos holding the wheat that nobody wanted. At the end of summer, another twister, this one at the southern edge of No Man's Land, hit the area. This furious funnel was strong enough to carry off the roof of a hotel. For the record, there had never been a drier summer.

The High Plains lay in ruins. From Kansas, through No Man's Land, up into Colorado, over in Union County, New Mexico, and south into the Llano Estacado of Texas, the soil blew up from the ground or rained down from above. There was no color to the land, no crops, in what was the worst growing season anyone had seen. Some farmers had grown spindles of dwarfed wheat and corn, but it was not worth

the effort to harvest it. The same Texas Panhandle that had produced six million bushels of wheat just two years ago now gave up just a few truckloads of grain. In one county, 90 percent of the chickens died; the dust had got into their systems, choking them or clogging their digestive tracts. Milk cows went dry. Cattle starved or dropped dead from what veterinarians called "dust fever." A reporter toured Cimarron County and found not one blade of grass or wheat.

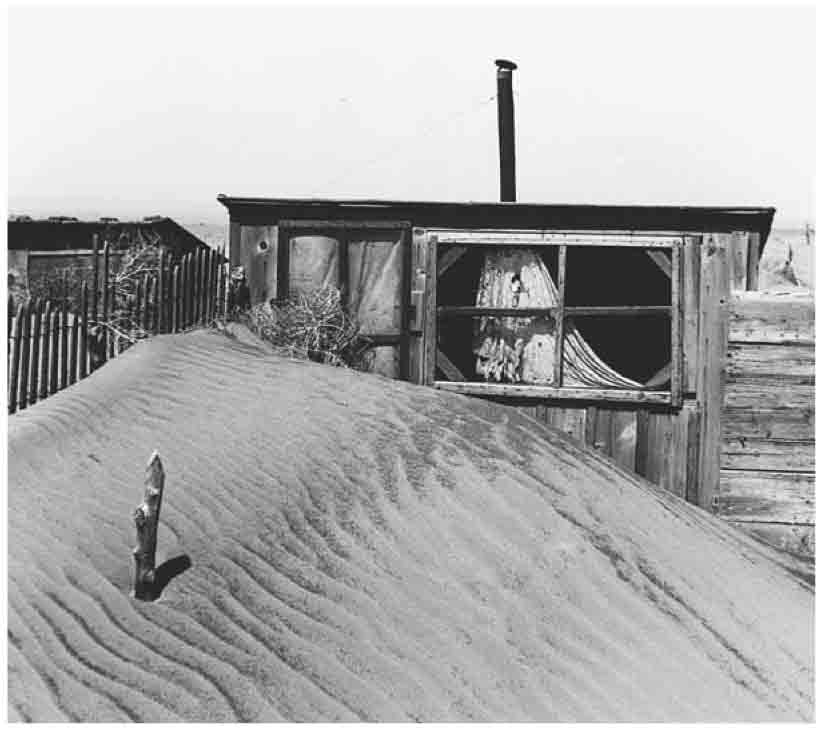

An Oklahoma farmhouse, 1930s

People from four states gathered in Guymon, Oklahoma, east of Boise City, to share stories and plead for help. The Red Cross was overwhelmed, with far more people begging for assistance than the agency could respond to. Some relief was on the way from one of the new agencies of the federal government: it would provide enough money to pay men to shovel dust from the streets of Guymon, Liberal, Texhoma, Shattuck, Dalhart, and Boise City. The wage was one dollar a day, and a man could not work more than three days a week in order to give others a chance.