They Marched Into Sunlight (61 page)

Read They Marched Into Sunlight Online

Authors: David Maraniss

Tags: #General, #Vietnam War; 1961-1975, #History, #20th Century, #United States, #Vietnam War, #Military, #Vietnamese Conflict; 1961-1975, #Protest Movements, #Vietnamese Conflict; 1961-1975 - Protest Movements - United States, #United States - Politics and Government - 1963-1969, #Southeast Asia, #Vietnamese Conflict; 1961-1975 - United States, #Asia

Protest leaders spread the word to get “the beef” up front, near the foyer and back by the interview room. It was at that moment that Michael Oberdorfer made the transition from sympathetic

Connections

photographer to full-fledged protest participant. He took off his army jacket, placed his Nikon camera in the large front pocket, and sat down right outside the interview room. The time had come for resistance, he believed. The war rolled on and on, the university seemed more beholden to corporate interests, hiding behind its cover story of impartiality. The only thing left was to stop business as usual at the university, Oberdorfer thought, even if only for that one day.

Lock arms, one marshal instructed. Hold your ground. Someone could be heard urging women to kick the officers in the balls.

Hanson found his way out and walked across the street to the police formation under the tower. He had given a final warning to the students, to no avail, he said. William Bablitch, the law student observer, had by then slipped outside to monitor the action and was standing near Hanson. He thought he heard Hanson say, “Let’s take a crack at ’em.” Emery turned to his men and said, “All right, let’s go and carry it out.” Hanson, in civilian clothes and without a helmet, led the way back toward the front of Commerce, followed by Sergeant Buss and his men. Jane Brotman gasped as she watched the sea of students on the plaza open a lane for the wedge of policemen who strode forward with a quickening gait, badges off, elbows out, nightsticks at the ready. The crowd fell in behind the officers, virtually engulfing them. Bablitch was in the group hovering just behind the last man in blue. Emery moved to the side and found a lookout on the rise above the plaza, between Commerce and Bascom, not far from where Brotman stood. He thought of it as “a command position” where he could “see what was going to transpire,” though in fact he could see nothing inside the building.

No more than two minutes after Hanson issued his final plea for the students to leave, here came Sergeant Buss and the wedge of cops, marching through the first set of glass doors. Al Roehling, at Buss’s flank, thought his state of mind was typical of the officers at that moment. He was, he would say later, “full of piss and vinegar and ready to go.” They reached the narrow vestibule, then moved through the second set of doors into the foyer. There was no space to gain footing, just a wall of people, and the human wall surged forward, pushing up against the oncoming force. The officers started flailing with their nightsticks but fell backwards into the vestibule. Chief Hanson was propelled “over and around bodies” and found himself “spilled outside the double doors.” He could not get back inside and was unable to lead or control the police force for the next several minutes. Sergeant Buss braced himself with his feet and arms against the corner of a door in the vestibule and remained there. One officer stumbled against a floor-to-ceiling plate glass window, accidentally breaking it into jagged shards with his nightstick, a frightening sound that added to the panic of the moment. As people around him backed away, the officer kept swinging his club at the window frame, now apparently attempting to clear it of sharp edges of glass. Some in the crowd saw only the raised nightstick, assumed police were on the attack, and started another surge forward in an attempt to keep them away. One officer who had been pushed out of the building caught sight of Emery standing on the slope and ran up to him and said, “Chief, we can’t do it.”

Chancellor Sewell was looking out the back window of Kauffman’s Bascom office with a clean sightline to the front of Commerce. He watched in horror as the first wave of officers marched in and stumbled back out.

This cannot be happening at our great university,

he thought to himself. His son Chip Sewell, a graduate student at Wisconsin, came bursting into the room.

“Dad!” he shouted. “Look at those cops going into the building. They’re going to beat the hell out of those kids!”

Sewell was lost, haunted, the well-intentioned man immobilized by events beyond his imagination. “Well, it’s out of my hands now, you know,” he said to his son. “They weren’t listening to me.”

Inside, in the few moments after the glass broke, there was an eerie silence. Then the police regrouped and reentered the foyer, this time without Hanson and with nightsticks raised. Once inside, they felt pressed against a wall, according to Buss, and then “really started using clubs.” John Lederer noticed that the officers “had a very set look on their faces.” Evan Stark, who had led the students to that moment, whose rhetoric resounded with calls for resistance, quickly decided when the time came that physical resistance “was not worth it” and managed to slip around the police and out the double doors, disappearing into the protective embrace of the gathering crowd. He said later that he had ordered everyone to leave when the police began their charge, but if so, fewer people heard this utterance than had heard Chief Hanson’s final declaration of an unlawful assembly.

Stuart Brandes, adrenaline flowing, found himself only a few yards from the police and about to become caught up in the human push against them. Here was his moment of decision, he thought. He could lend his considerable strength to the surge, probably without getting caught, and in so doing participate in what he considered a violent act against police. In that split second, with the cops moving toward him and the students pushing back, he had to decide whether he was willing to resort to force. The answer was no. He was a liberal, not a radical. Although against the war, he was not confrontational and was not going to fight the police. He found an opening and made his way partway up the eastern stairwell, standing amid a group of business school students who were there jeering the protesters and cheering the cops. That is what they were doing, that is, until a few officers rushed the stairs, billy clubs flashing, unwittingly going after their own supporters.

Near the front door police were able to grab a few demonstrators and drag them outside and up the knoll toward the waiting paddy wagon. One of the first to be arrested was Vicki Gabriner, Miss Sifting and Winnowing, who darted in front of the cops as they arrived at the entryway and went limp and started shouting at them as they hauled her away. Her arrest was pure guerrilla theater, and she made the most of it, resisting vociferously as two policemen dragged her by the arms, slowing them down enough so that every movement was captured on film. One of the defining pictures of the day was of Gabriner’s painted face staring out the back window of the paddy wagon.

Lynne Cheney, the English doctoral student who also taught freshman composition, and her husband, Dick Cheney, the political science graduate student, could not recall later precisely where they were as the Dow protest unfolded that day, but they retained a strong memory of seeing, and being revolted by, the antics of the mimes. In an interview with

The New Yorker

three and a half decades later, when her husband was vice president of the United States, Lynne Cheney said that she distinctly remembered “going to class and having to walk through people in whiteface, conducting guerrilla theater, often swinging animal entrails over their heads, as part of a protest against Dow Chemical.” What surprised her most, she said, “was that you would enter the classroom and here would be all these nice young people who honestly wanted to learn to write an essay. That, in a sense, was the real university, but this other was what was attracting so much attention.”

The breaking of the glass had “scared the hell” out of Officer Roehling, who was afraid that one of his fellow officers would be wounded by the shards. He also felt overmatched by the crowd, and he started swinging his nightstick with abandon. Roehling knew nothing about the proper way to use a baton in a hostile crowd, he would admit later. Madison police had not been trained in that yet, aside from four who had taken a brief riot control course in Chicago. What they should have done, and would be taught to do in later confrontations, was to keep their batons in front of them, using them two-handed to poke and jab and protect. Instead they lifted the clubs above their heads and started swinging. There was, Roehling recalled, “a lot of overhead swinging.”

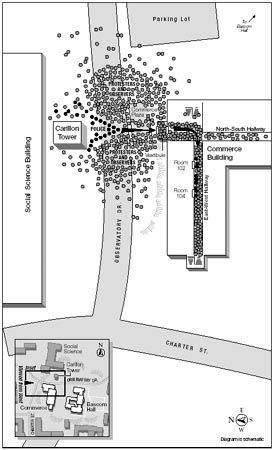

Confrontation at UW Commerce Building

Eric Nathan, a junior from Manhattan, was in the surging mass just inside the front doors when the pushing and swinging began. He and his friend Donald Lipski had debated whether to take part in the demonstration at all, wondering about the worthiness of the linkage between Dow Chemical Company and Vietnam. Even during the march up the hill they had debated whether to be supportive pickets or obstructionists but finally decided to go inside and “take our stand.” They sat cross-legged in the corridor at first and experimented with interlocking their legs, before deciding that was too dangerous. Lipski felt “an adrenaline rush like pregame in a locker room” as the police approached. He and Nathan were part of the shoving match at the front door, with police trying to force their way in and students attempting to keep them out. When nightsticks went up, Nathan, feeling a sense of shock and outrage, decided that he did not want to “mess around” with the police. He raised his hands above his head in a “don’t hit me” gesture and managed to snake his way through the melee untouched, stumbling into the roiling crowd outside. John Lederer got out of harm’s way by rushing up to the stairwell, near Brandes and the gaggle of business student bystanders. He watched the melee near the entrance as police started swinging. “Some of the people were grabbing onto their clubs, mostly to keep them from being shoved in their stomach,” he reported. “They were pushing with their hands and the police officers would yank their clubs back to get them free of the hands, and the next thing they were hitting people and seemed to be very indiscriminately hitting people. They were definitely hitting people on the head.”

Some protesters were resisting the police, Lederer noted, and some were not. He counted himself among those not resisting. An officer stomped toward him and jabbed him in the stomach. Lederer put his hands to his head for protection.

Don’t get clubbed, and don’t look like you’re resisting,

he said to himself. He tried to walk out the double doors under his own power. Another policeman shoved him forward and he fell to the ground and was hit across the back of the neck. He got up and “was sort of half-shoved and half moved myself out of the building.” Stuart Brandes, from his position on the stairs, saw an opening through the foyer and vestibule and decided to make a run for it. He was afraid of being collared by the police, thinking that he might be “going out the door and right out to a paddy wagon and right out of school.” He made his way, shouting all the while that he was leaving as fast as he could, and though he was jostled, he managed to avoid the nightsticks. Brandes reached the second set of glass doors and stepped out to the plaza and saw a ring of officers in front of him and the swirling crowd behind them. He decided to turn sharply to the left, following the side of the building a few yards until he looked down and faced a sudden ten-foot drop-off.

Below him cut into the earth was a cement walkway leading to a basement utility room, and standing down there looking up at him, urging him not to jump, was Maurice Zeitlin, the assistant professor of sociology. Zeitlin did not support the obstructive protest and had not participated in the demonstration but felt connected to the demonstrators. He had sponsored the faculty resolution the previous spring that had sought to ban Dow and other military contractors from recruiting on campus, and only the day before he had been a featured speaker at the noontime rally on the Commerce plaza against Dow. Shortly before the confrontation now, he had attempted, with no luck, to persuade the police not to enter Commerce. When all else failed, he noticed the dangerous precipice to the side of the front doors and decided to station himself down at the bottom, thinking that he might catch anyone who jumped or fell.

Within a few minutes the first wall of protesters inside had vanished. Police had gained control of the foyer and started to move down the east-west corridor toward the obstructionist students in front of the Dow interview room. It was “kind of close quarters” in the hallway, Sergeant Buss later recalled, and protesters “laid on the floor, kicked at you, spat at you, cursed you—but it wasn’t the violent type where we met the swinging fists and trying to choke you and so on.” Buss said he and his fellow officers “did manage to use” their clubs “and a couple of students were knocked to the floor and we then started taking them by the arms or any way we could get them. We kind of broke their resistance and started…pushing them back through the door and there were enough policemen so that one guy would get hold of him, the next guy would take him, the next guy, and out the door they would go, so finally we just had them out of the way.”

Captain George Schiro, in charge of the fourteen Madison and campus officers who had been stationed inside the building all morning, started moving away from room 104, where the Dow interviews were supposed to have taken place. Curly Hendershot had given up any pretense of conducting interviews by then and had retreated through an interior doorway into the business school’s administrative office, where a few secretaries and faculty members remained. Schiro edged down the hallway with his back pressed against the wall, as soon as he heard the commotion at the front. As he neared the foyer, he started grabbing students, trying to eject them. He was without a nightstick himself, but he saw the other officers wielding their batons. It was only in self-defense, he thought. Bob Hartwig, a sergeant in Hanson’s university force, had been standing near Schiro outside the Dow interview room when the police wedge entered the building and the glass started breaking, “sending a jolt through everybody.” He tried to usher students out the far western stairwell, but many would not, or could not, leave. Utter chaos, he thought.