Think Like an Egyptian (30 page)

Read Think Like an Egyptian Online

Authors: Barry Kemp

The Egyptians used terms for a malfunctioning heart such as “weary” “hot,” “kneeling,” “flooded,” and “dancing.” Believing that arteries carried air and connected up with the digestive areas, it seems not illogical that their word for the stomach was “the heart’s mouth.”

There were two words for heart,

ib

ib

(

ib

) and

૩ty

૩ty

(haty),

which were used interchangeably in the medical papyri, although some nuances existed. In other sources

ib

ib

was the preferred term for the heart as the seat of thoughts and emotions, and is sometimes translated as “mind,” “opinion,” or “will.”

ib

ib(

ib

) and

૩ty

૩ty(haty),

which were used interchangeably in the medical papyri, although some nuances existed. In other sources

ib

ibwas the preferred term for the heart as the seat of thoughts and emotions, and is sometimes translated as “mind,” “opinion,” or “will.”

A theological text describes the primacy of the heart in the phenomenon of life, created in time past by the god Ptah. The thoughts of his heart, uttered by his tongue, summoned up life:

Sight, hearing, breathing: they report to the heart, and it makes every understanding come forth. As to the tongue, it repeats what the heart has devised. Thus all the gods were born and his Ennead [company of nine gods] was completed. For every word of the god came about through what the heart devised and the tongue commanded. Thus all the faculties were made and all the qualities determined.... Thus life is given to the peaceful, death is given to the criminal. Thus all labor, all crafts are made, the action of the hands, the motion of the legs, the movement of all the limbs, according to this command which is devised by the heart and comes forth on the tongue and creates the performance of every thing. Thus it is said of Ptah: “He who made all and created the gods.”

The heart was one of several spiritual components of a person, revealing itself particularly at the moment when, after death, it was weighed in the hall of judgment against the symbol of truth (see no. 58, “Truth,” and no. 90, “Balance”). If guilty of wrongdoing, it would weigh heavily and would reveal the owner’s misdeeds. A text composed for the Book of the Dead, wrapped in with a mummy would guard against the heart’s revelations. Written in tiny hieroglyphs on the base of a scarab-shaped amulet of dark stone, it would proclaim:

Spell for not allowing the heart of N to create trouble for him in the necropolis. He says: “O my heart of my mother, my heart of my mother, my heart of different ages: stand not up against me as witness, create no trouble for me as a witness, create no trouble for me among the judges. Do not weigh heavy against me in front of the keeper of the scales. You are my spirit [ka] which is in my body, the Khnum (creator-god) who sustains my limbs.”

With this safeguard the heart was returned to the body after mummification.

In contrast to this somewhat pragmatic (and some might say cynical) approach is the advice given by a king to his son to relish the rewards of good deeds: “When a man remains over after death, his deeds are set beside him as treasure, and being yonder lasts forever.... He who reaches them [the judges] without having done wrong will exist there like a god, free-striding like the lords of eternity”

76.

TO BE BORN

Despite beliefs that human lives originated from clay on a potter’s wheel by the creator-god Khnum, or were the “tears” of god (this based on a pun between the words for “tears” and “mankind”), Egyptians knew that sexual intercourse was the basis of reproduction. In one story a lady is attracted to a blind vagrant found lying amid the reeds and has him brought into her house. “He slept with her that night and knew her with the knowledge of a man. She conceived a son that night.” Although Egyptian temples relentlessly maintained that the king was born from a union between his mother and the sun-god, secular literature accepted that, in reality, the royal family was no different from any other. A king who lacked a son prayed to the “gods of his domain.” “That night he slept with his wife and she [became] pregnant. When she had completed the months of childbearing, a son was born.”

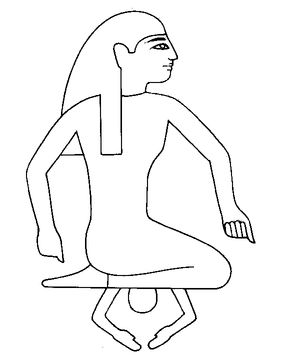

Sources, including the childbirth hieroglyph itself, suggest that women gave birth in a squatting position resting on one or more specially made bricks decorated with protective symbols, often a picture of the deities Bes and Taweret, and pictures or symbols of the goddess Hathor. A description of childbirth is found in a tale of the miraculous birth of triplets, to the wife of a priest of Ra the sun-god, destined to be future kings of Egypt. A group of goddesses are sent out by Ra himself to assist with the delivery, one of them, Meskhenet, having the same name as that given to the birthing bricks. They transform themselves into a troupe of female entertainers, with the creator-god Khnum changing into their porter. They find the father “standing with his loincloth untied” and eager that they assist his wife:

Isis placed herself in front of her, Nephthys behind her, and Heket hastened the birth.... The child slid into her arms, a child of one cubit, strong boned, his limbs overlaid with gold, his headdress of true lapis lazuli. They washed him, having cut his navel cord, and laid him on a pillow of cloth.

The goddesses tell the priest of the successful delivery of the triplets, and he pays them with a sack of barley from which to make beer. Subsequently the wife “cleansed herself with a cleansing of fourteen days.”

A category of stylized pictures, many from Deir el-Medina and hastily drawn on flakes of limestone, celebrates the events after childbirth. They show the mother nursing her child on a stool or on or beside a wooden bed, decorated with protective symbols including the god Bes, a protector of women in childbirth. The stool or bed is beneath a canopy twined with the leafy convolvulus plant, though it is not clear whether this was a room in the house decorated for the occasion or was a place specially constructed for childbirth. Mothers could expect a prolonged period of breastfeeding. The sage Any reminds his reader that: “When you were born after your months, she was yet yoked [to you], her breast in your mouth for three years.” Some could afford a wet nurse, a woman with her own baby and the capacity to feed two. A workman at Deir el-Medina named Userhat paid a wet nurse three necklaces of red jasper, one piece of timber, a basket, an ivory comb, a pair of sandals, and ajar of oil for this service (perhaps his wife had died in childbirth).

Pregnancy and childbirth fell under the care of Egyptian “medicine,” a complex mix of rational practice and magic. Surviving papyri contain tests for fertility, for pregnancy, and for determining the sex of the unborn child: “Emmer and barley, [put] like dates and sand in two bags, the lady should moisten with her urine every day. If both sprout, she will bear. If the barley sprouts, it means a boy; if the emmer sprouts, it means a girl. If neither sprouts, she will not bear a child.” They offer remedies for a range of gynecological problems. For example, when the pubic region is “very swollen due to giving birth: you should then prepare for her 1 hin [450 milliliters] of new oil, to be soaked into her vagina.” These medical texts recognize—significantly, because the texts were almost certainly written by men—that women do not necessarily want to keep bearing children, and offer contraceptive remedies to halt fertility: “Beginning of the prescriptions prepared for females to allow a woman to cease conceiving for one year, two years, or three years: acacia leaves [or thorns?], carob, dates; grind with 1 hin of honey, spread it on a strip of linen, and place it inside her.”

77.

TO COME INTO EXISTENCE

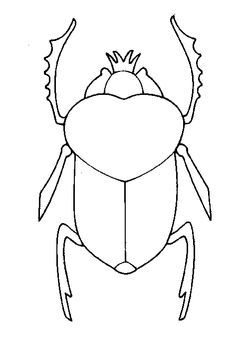

The hieroglyph depicts a scarab beetle

(Scarabaeus sacer),

sadly no longer common in Egypt. It stands out from other insects by forming a perfectly spherical ball (about the size of a tennis ball) of mud and dung around its eggs, which it can then roll to a safe place. Eventually the eggs hatch and new beetles emerge. The beetle became a vivid metaphor both for the phenomenon of coming into existence, expressed through the verb

pr (kheper),

pr (kheper),

and the movement of the sun across the

sky

the sun itself being regarded as the source of life. The beetle was named “Becomer” (Khepri) and was considered a manifestation of the sun-god, who “wearies himself with toil” as he pushes the disc of the sun across the heavens.

(Scarabaeus sacer),

sadly no longer common in Egypt. It stands out from other insects by forming a perfectly spherical ball (about the size of a tennis ball) of mud and dung around its eggs, which it can then roll to a safe place. Eventually the eggs hatch and new beetles emerge. The beetle became a vivid metaphor both for the phenomenon of coming into existence, expressed through the verb

pr (kheper),

pr (kheper),and the movement of the sun across the

sky

the sun itself being regarded as the source of life. The beetle was named “Becomer” (Khepri) and was considered a manifestation of the sun-god, who “wearies himself with toil” as he pushes the disc of the sun across the heavens.

Other books

Los Perdidos: The Novel (Sons of Glory Motorcycle Club Romance) by Daphne Loveling

Plaguelands (Slayers Book 1) by Jae Hill

Midnight Shadows by Lisa Marie Rice

The Odd Job by Charlotte MacLeod

Unfriended by Katie Finn

Code Breakers: Beta by Colin F. Barnes

A Non-Blonde Cheerleader in Love by Kieran Scott

The Barefoot Queen by Ildefonso Falcones

Ladybird by Grace Livingston Hill

ZEKE by Kelly Gendron