Thirty Rooms To Hide In (17 page)

Read Thirty Rooms To Hide In Online

Authors: Luke Sullivan

Tags: #recovery, #alcoholism, #Rochester Minnesota, #50s, #‘60s, #the fifties, #the sixties, #rock&roll, #rock and roll, #Minnesota rock & roll, #Minnesota rock&roll, #garage bands, #45rpms, #AA, #Alcoholics Anonymous, #family history, #doctors, #religion, #addicted doctors, #drinking problem, #Hartford Institute, #family histories, #home movies, #recovery, #Memoir, #Minnesota history, #insanity, #Thirtyroomstohidein.com, #30roomstohidein.com, #Mayo Clinic, #Rochester MN

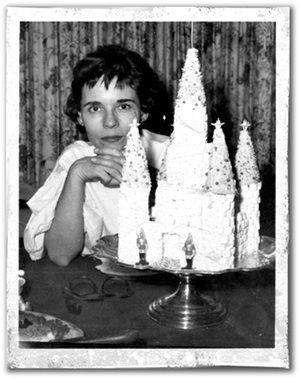

Christmas, 1963: Mom with one of her cute holiday creations. She’s already showing the strain on her face.

Mom, December 16, 1964

My good brother Jimmy just phoned to tell me about your illness, Papa. As I told Jimmy, if only I had delayed the move out of the Millstone by two short days I could have found a housekeeper and come to you in Florida. But to leave the boys out here in this little house at this time is out of the question. They are already so very upset by this move that I cannot leave them even for a few days. I hope you will not think me callous – it is a hard choice to make – but I hope you can accept my judgment that I must stay here.

Mom, December 17

Still I have had no word on Poppa’s condition. I have just sent a wire hoping it will find you at the hospital. I am concerned for both of you and feel so very far out of contact. I trust you’ll call when you receive the wire.

In the mean time, our lives here continue along such as they are. This morning the temperature was 14˚ below zero. Naturally our cars sitting unprotected on the street would not start. It was 9:00 before the truck arrived to put us in motion. So the boys were all late to school.

You should have seen us in this little house – all in our boots, mittens, caps, coats, ready to run when our cars were started: Kip standing before the stove clock delivering his citizenship speech, Danny & Jeff practicing guitars, Christie showing Collin magic tricks, the dog & the cat caught up in the excitement and chasing one another around the Christmas tree. And I, clomping about in my big boots, trying to get some housework done. Kip shouted out over the hub-bub [referring to the current Shirley Jackson book about a house full of crazy people] “We’ve always lived in this castle!”

People continue to call – to offer their help and sympathy – but truly there is nothing anyone can do. Two have invited us for Christmas Day dinner, but of course that is a day I would not go anywhere.

By Christmas Day, Myra would in fact travel 1,500 miles. Just as we were settling in for as normal a holiday as we could muster, her brother Jimmy called to say a stroke had landed RJL in the hospital; he could not speak, move, his vital signs were not good and no matter what her circumstances were in Rochester, Jimmy said, it was time to come.

The next train to Florida left at noon and Myra had just one hour for emotional triage. Since none of us lay dying, the choice seemed clear and so on the way out the door to the train station, she handed the reins to Kip and Jeff with orders to “make Christmas happen” for the little ones. But within a day Kip and Jeff decided to strike the tents and move the family back to the Millstone for the week. They packed it all up: the Christmas tree, the pets, and the bags of unwrapped presents Mom had hidden in the basement. We moved back into the drunk’s castle for a Christmas not one of us remember. There’s blank spot in our collective recall. We have photos of Christmas, ’63; films of Christmas, ’65; but of ‘64, nothing but a single image.

Where our father was on that Christmas morning none of us can recall; we know only he wasn’t with us. There was no tree either. (Dad had “sent away” the tree Kip had brought from the little house, lashed to the roof of the Plymouth. “She” had picked it out.) What we

do

remember of Christmas morning, 1964, is the six of us gathered in our parents’ empty bedroom standing in our pajamas around a pile of bags full of unwrapped gifts. As we pawed our way through the pile guessing at what was whose, nobody looked up from our business to ask, “Isn’t this weird?” None of us wondered if the neighbors’ kids weren’t also pawing through bags of unwrapped gifts in their parents’ empty bedroom. This is just the way it was at the Millstone. If there was trauma it was limited to 7-year-old Collin whose belief in Santa Claus was surprised that morning the way Sonny Corleone was surprised at the tollbooth in

The Godfather

.

* * *

As we sit in the study of my mother’s little Minneapolis house discussing Christmas of 1964, it’s clear her decision to leave for Florida still troubles her.

“You couldn’t do everything, Mom,” I tell her. She shakes her head, says, “But still.”

She holds one of the books bound years ago by her father. Burned into the spine in a silver-colored ink is RJL’s script identifying the year: 1964. The volume is thicker than previous years, the letters more numerous now; she no longer cared what Roger thought of her letter-writing. The letters here begin to take on a gallop, one after another, reeling out the story: her unraveling marriage, her collapsing husband, her disintegrating life, and of course her Christmas trip to Florida.

Grandpa had finally recovered and when he was released from the hospital on Christmas Day, Myra took the train back to Rochester.

Mom, now back in Rochester, December 29, 1964

I unpacked, took a bath, cleaned up the little house, and even took a nap. I could not go get the little ones at the Millstone because the two big boys (asleep in the basement) still had the car loaded from a Pagans’ engagement the night before. It was nearly noon when Kip and Jeff came upstairs and my little ones had been calling from the Millstone every 15 minutes to ask when they could “come home.” When Kip and Jeff left, it was 10˚ below. At the Millstone, they loaded the car to the roof with mattresses and blankets and Christmas gifts and dirty clothes, one cat and my 6 boys.

You know with what joy I greeted them all again. We had a peculiar supper, being without an ice-box here, but we were all so happy no one noticed.

Grandpa [transcribed as is]

dear chn here goes foran expriment – typing wyth my right frtrfingrt and i bet i make so mzny mistakes that yt will bw herder to read than my usul spastic scrawrl.… appetite reamins ok. and if your t-v carrisx the same cultursl ads as does ours, you will understand me when i say that carters littlr liver pills or ex-lax produce desirable results. your mother sez i am showing more skill in the use of my walker. but i declare to you that progfrtess seems a bit slow. i cannot use my right hand at all , but enuff of this tripe.

Mom’s letters, December 30, 1964

Tomorrow is New Year’s Eve. The Pagans are on stage somewhere, so I will see the last of 1964 with my four little ones. And glad I am to see the last of ‘64 – the most miserable year of my life. But “things are looking up” – so I am welcoming ‘65.

Tonight Danny has a friend to spend the night with him. And Kip brought his Linda home about 8:30. We all watched the “Danny Kaye Show” and then sat in the living room eating candy and talking – in the middle of which Collin got out of bed (hearing Linda, whom he loves), Christie took a bath, Danny & his friend were playing guitars, the dishwasher spurted water all over the kitchen floor and the bathroom doorknob mysteriously locked itself (the punch-in-the-middle variety), requiring the concerted and individual efforts of all of us with a tiny screwdriver to open it again. (“We’ve always lived in this castle!”) But dear heaven, it was fun and relaxed and fearless and happy!

The Millstone in winter.

It is mid-winter – January, 1965 – and the sun is setting.

The driveway gate to the Millstone is open and the two Irish wolfhounds have run away.

Snowfall has gathered unplowed for a month and almost entirely blocks the driveway. Brother Chris, 13, is sitting on the stone gate posts at the end of the driveway looking at the house he used to live in. A scarf covers his mouth. Of the six boys, he is the one who looks most like his father; aquiline nose and intelligent eyes that have a haunted look – like the house at the end of the driveway.

No one knows Chris is here. He’d simply walked out of the little house in Elton Hills, trekked the six miles over back roads through Rochester, and arrived in his old neighborhood as darkness fell. He wants to look at the Millstone for a while but the 10-degrees below drives him in.

He’s pretty sure his father is not here or the sporty little Italian MG would be parked out front. The front door is unlocked and he enters. His feet crunch on something. In the dim light it’s hard to tell if the dried puke is from one of the wolfhounds or his father.

There is trash everywhere, with no overturned garbage can nearby to explain it. This trash has been dropped right where it is – tin trays of Swanson TV dinners, empty bottles of mixer, a china cup with coffee dried to a lacquer. Across the room in the dog bowl, Chris sees the wolfhounds have been fed Cheerios. The empty cereal box, too, has simply been tossed to the floor. It is a mess that looks

angry

; a home vandalized by its owner.

Chris walks through the kitchen to the pantry and clicks on the light. The red and white cans of soup on the middle shelf are gone, moved to the Elton Hills house along with most everything else. But there’s a can of corned-beef hash he could heat, and abandoned out on the porch Chris finds a frozen can of Coca-Cola with its new-fangled pull-ring top. He takes his dinner to the living room, builds a fire, and after opening the cans sets them near the flames.

As they warm, he watches his shadow dance across a strange living room. There’s a reading lamp but no chair to read in. Where the sofa was are four square imprints in the carpeting; its absence gives the matching coffee table an unmoored look.

The corned-beef hash is passable but the Coke is without fizz and he sets it down. He goes up to his old room and lies on the plywood frame where his mattress used to be. As the coals settle in the fireplace downstairs, he falls asleep under his coat. His father never comes home that night.

* * *

While our parents were separated, all six of us took trips back to the Millstone; sometimes together, sometimes alone. We’d walk around the place like it was a crime scene and even with winter sunshine pouring white through the windows the feeling in every empty room was “something bad happened here.”

We’d visit during the day, running over from school during lunch period so we wouldn’t risk meeting Dad. To see what

,

we weren’t sure; to dig through our disassembled rooms perhaps; a bit of childhood archeology. There is a sadness to the detritus of a separated household. Each particular thing, even in its correct place, has a discarded look. Everyday objects like a pen in a drawer, or a pair of ice skates in the entryway, feel abandoned. This spatula on the kitchen floor, is it Dad’s spatula now? Mom’s? Ours?

We were angry at Dad for betraying and exiling us, so we came for mischief as much as curiosity. During one of these lunchtime visits, Chris and I went through the house and tilted every framed picture on the walls a few degrees to the left. We hoped Dad would return home, mix a stiff one and seeing the ever-so-slightly canted pictures wonder, “Ye gads, has at last the drink turned on me?” We poured out bottles of Old Grand-Dad, went though his

Playboy

magazines, and picked through the rooms of any brother who wasn’t with us. After lunch, we’d return to school where Mom would take us back to the tiny house in Elton Hills.

Had we not been born into a home like the Millstone, it’s likely we’d have been happy in the Elton Hills house. It was an honorable dwelling. It’s still there on 13th Street and has likely been nest to several generations of happy children. But as refugees from the Millstone we felt the crunch of space, the loss of privacy.

On the first floor at Elton Hills, Mom had one of the two bedrooms and Collin and I shared the other. The unfinished basement was one large room and the older four each claimed a corner as his own, with the backs of dressers and footboards of beds indicating where one room ended and another began.

That Roger could sleep at night while exiling his wife and six children to a tiny house is testimony to the miracles of fine charcoal mellowing in the sugar-maple barrels of Kentucky distilleries. But now, with nobody to argue with when he came to, he began driving out to the Elton Hills house to pick fights. And the phone calls began. Hundreds of phone calls.

Entries from Kip’s diary, February and March, 1965

Dad called six times. Mom doesn’t know what’s next. … Dad over here. One more try at reconciliation. Mom and Dad can’t even talk. He just bitched about the car situation and money. … Dad called for seventh time at 10 at night, “just to talk.” Poor lonely bastard. … Dad has been bitching about Mom’s reading. How it “hurt the family.” Christ.

Mom, January 22

I will not go back to Roger yet. I have had enough experience with these periods of abjection to know that they are short-lived.

I cannot live with him until some very fundamental changes are made in him. I simply cannot step back into that chaotic, violent, senseless life.

Mom, February 5

At no moment since December 11th have I had even a flicker of regret over leaving or a beam of hope I could live with him again.

I am no longer (except spasmodically) angry or disgusted or outraged – my foremost emotion toward him is tiredness. I’m tired of trying to deal with him, tired of hearing the same stuff over and over again, tired of shaking off the clinging, whining, consuming dependence. Tired tired

tired!!!

And I wish I could decide what to do. If I were dealing with just a sorry marital situation, I would get a divorce and be done with it. But I am tangled with a psychiatric problem and such decisive action might threaten my economic security and the futures of my boys. There are so many decisions to make.

Mom, February 10, 1965

I have got to force this situation. He called yesterday to say he was done “jumping through hoops,” that it was “high time I quit having my way” and that he was getting a divorce and keeping the house. Like it or not, I am going to force him to sell that house so that I can buy a house with the minimum amount of space for these boys to live in.

Mom, March 15

Thursday morning at 10:30 I have an appointment with the lawyers to hear them explain why they think 1/4 of Roger’s salary is adequate for seven people to live on. … When I consider how breathlessly busy I am hour by hour every day, I wonder how I can handle a steady job – a problem I may not have to face very soon since I am having no luck at all finding work. If I had ability to write shorthand it’d be much easier to find stenography work. I have brought home my shorthand text and will review it until such time as I can get a course started.

From Grandpa’s letters, April 16

Do not give up. A way will open.

If divorce law seems unfair today, in the ‘60s it was worse. Somehow an Olmsted County judge was able to keep a straight face when he awarded my mother just one quarter of Roger’s salary – 1/4th of the money to house, feed, and clothe 7/8ths of the family. Unable to find a stenography job, Myra temped for the U.S. Census Bureau and then one day came home to discover that the Elton Hills house was being sold. She had to move the family again.

“I simply could not find a place for the seven of us at any figure I could afford,” remembers Myra. “There seemed to be nothing left to do except to crawl, humiliated, back to the Millstone.”

Grandpa’s letters

Your wire of last evening was troubling, indeed. Perhaps the return to the ‘Stone has the advantage of a three-month playground for the boys. Otherwise, one fears the effect on you.