This Great Struggle (27 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

Providence had already granted Lee a boon in the slowness with which McClellan had responded to the information in Special Order Number 191. Franklin’s lethargy and caution was a second gift. After that, one thing after another seemed to go Lee’s way. Confederate troops had to fall back from their positions on South Mountain that night, but McClellan kept his army almost stationary on September 15. Meanwhile, the Confederates had surrounded Harpers Ferry, and Jackson was presiding over efforts to capture the town and its garrison. Union commander Colonel Dixon S. Miles pulled almost all of his troops back into the indefensible town, virtually giving away the key high ground that overlooked it. Then on the morning of September 15 when Jackson launched his attack, Miles was so quick to order his command to surrender that he probably would have been court-martialed when Union forces next got hold of him had he not been struck and killed by one of the last artillery shells the Confederates fired before the white flag went up.

The surrender of Harpers Ferry gave the Confederates ten thousand Union prisoners and opened the way for the Army of Northern Virginia to reunite. Lee brought them together near the town of Sharpsburg, Maryland, about a dozen miles due north of Harpers Ferry, ten miles west of South Mountain, and a mile or two east of the Potomac, which here flowed from north to south. He deployed them facing east, toward South Mountain and McClellan’s approaching army, on gently rolling terrain, with the valley of Antietam Creek in front of them.

Lee still had high hopes for victory, planning to repeat the successful formula of Second Bull Run. If it worked, he would lure McClellan into bloodying the Army of the Potomac in fruitless assaults and then conclude the battle with another devastating Confederate flank attack like the one with which Longstreet had ruined Pope on the plains of Manassas. The plan was audacious in the extreme. Lee’s army was weakened by a summer of brutal campaigning and had been shedding stragglers steadily since it had marched north from Richmond. Worse, Lee’s position, although presenting reasonable cover and good fields of fire, had key weaknesses. In front of it, Antietam Creek, with three stone bridges and several fords, offered only a minor obstacle to the enemy, while behind Lee’s position, the Potomac was crossable at only one point, Boteler’s Ford. Getting an army across Boteler’s Ford would take hours, and if disaster befell his army, Lee would not be able to withdraw any substantial number of his troops via that ford before they were overrun and captured. Defeat on this field would be final for Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia.

Lee arrived near Sharpsburg on September 15 and began deploying the first units of his army, numbering about eighteen thousand men. The first elements of the Army of the Potomac arrived on the far side of the Antietam Valley that afternoon, and by nightfall virtually all of McClellan’s troops were arrayed there. Thus, on the morning of September 16, Lee’s eighteen thousand faced some ninety thousand Federals, and McClellan had the opportunity to crush the Confederate force at Sharpsburg and take it and its commander as prisoners. As Lee had apparently calculated, the Union commander hesitated. Convinced that Lee had one hundred thousand or perhaps one hundred fifty thousand men, McClellan spent the day studying Lee’s position through a very large telescope mounted just outside the house he was using as his headquarters. While McClellan and his top generals took turns squinting into the eyepiece, most of the rest of Lee’s army arrived from Harpers Ferry.

McClellan planned to push one wing of his army across Antietam Creek north of Lee’s position and open the battle by having it attack southward between the Antietam and the Potomac. Union preparations on the evening of the sixteenth were obvious, and Lee had Jackson’s wing of his own army positioned to meet the Union thrust. Action began at first light on the morning of September 17, about 5:30, and raged intensely on the northern end of the battlefield for the next five hours.

McClellan dissipated his advantage in numbers by committing his units piecemeal, one corps at a time, so that the Confederate defenders were able to shift to meet them. With the southern half of the battlefield quiet, Lee pulled troops out of line there to support Jackson on the left. Even at that, the Federals nearly broke through. The fighting raged back and forth, and the cornfield of a farmer named Miller changed hands as many as fifteen times and was left thickly strewn with corpses and with nearly every cornstalk cut down by bullets. By late morning the Federals on this front had reached their initial objective, a plain, whitewashed meetinghouse of a sect of German Baptists whom locals derisively called “Dunkers,” but the Union attack was spent and could go no farther. Jackson, who realized that his line had several times that morning been within an ace of total collapse, attributed his successful defense to divine intervention.

About that time, fighting flared up in the center of the Confederate line, where a stray Union division had at first attacked by mistake. The Confederate position was extremely strong, but Lee and Jackson had left only the minimum defenders in their desperate quest to find every available man to hold the line near the Dunker Church. Both sides now fed reinforcements into the fight in the center, which focused on a sunken road—a dirt road eroded below surrounding ground level—that the Confederates used as a ready-made trench. One Union brigade after another attacked the Sunken Road until finally the Confederate line gave way. Longstreet, who commanded this sector, had no troops left to plug what was now a yawning gap in the center of his line. He had his artillery open fire on the pursuing Yankees and even assigned his own staff to man one of the guns after its crew had been shot down.

Though the troops that had captured the Sunken Road were fought out, McClellan had plenty of reserves and could have poured them into the gap, ripping Lee’s army in two and completing its destruction. Franklin, whose Sixth Corps had not yet fired a shot in the battle, requested permission to advance and exploit the breakthrough, but McClellan refused. Sometime later, a division commander in the Fifth Corps, which had also been unengaged, suggested to McClellan that his corps ought to be ordered in. Overhearing the exchange, Fifth Corps commander Fitz John Porter cautioned McClellan, “Remember, General, I command the last reserve of the last Army of the Republic.” This was errant nonsense, but it was good enough for McClellan, who left the Fifth Corps idle.

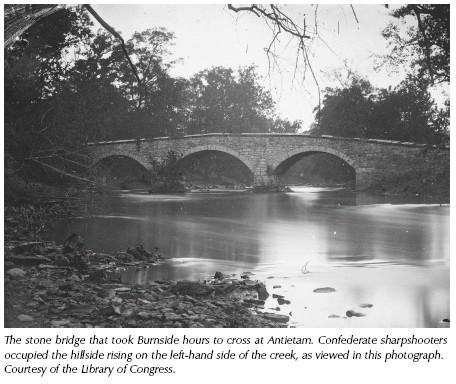

Meanwhile, on the southern end of the battlefield, Ambrose Burnside, with his Ninth Corps, was supposed to be diverting Confederate attention by crossing to the west bank of Antietam Creek. Here the Confederate line ran along the slope of a bluff that towered one hundred feet above the creek. Burnside was a highly intelligent, dedicated officer who on this day began giving the first indications that he was extremely inept at handling large bodies of troops on a battlefield. Although the creek was fordable in many places, Burnside focused his attention on a narrow, three-arched, stone bridge toward which he launched several attacks that either were broken up by the fire of a few hundred Confederates on the bluff or else veered off course and reached the wrong stretch of the creek. While Burnside strove earnestly but ineffectually for three hours to get his men across the waist-deep creek, McClellan dispatched a succession of increasingly insistent messages demanding action, and Lee drew off all but a handful of the units that had been guarding Burnside’s front and shifted the troops to help hold his desperately hard-pressed left and center—exactly what Burnside was supposed to prevent.

Finally, around 1:00 in the afternoon, Burnside got a compact column of troops to charge straight across the bridge into the teeth of the Confederate fire. At almost the same time, one of his divisions found and used a ford about two miles downstream and flanked the Rebels. At last Burnside’s corps streamed across the creek, formed its line atop the bluff on the west bank, and then had to wait in ranks for two hours while ammunition was brought up via the narrow bottleneck of the bridge. At last, at 3:00 p.m., the Ninth Corps swept forward and crushed the weakened right flank of Lee’s line. Fleeing Confederates ran through the streets of Sharpsburg while Burnside’s formation bore down not only on the town but also on Boteler’s Ford, Lee’s only line of retreat.

In the midst of their triumphant advance, the Federals were stunned when a new wave of Confederates struck their flank. A. P. Hill’s division was the last of Jackson’s troops to leave Harpers Ferry after processing the prisoners and booty there, and it reached the battlefield just in time to counterattack the Ninth Corps. Flanked, surprised, and further confused by the fact that many of Hill’s Confederates were wearing Union uniforms captured at Harpers Ferry, the Federals fell back with heavy losses. They regrouped atop the bluffs and still outnumbered the Confederates in front of them, including Hill’s division, by a margin to two to one. Burnside, however, had had enough and ordered his corps to fall back to the east bank of the creek and assume the position in which they had started the day.

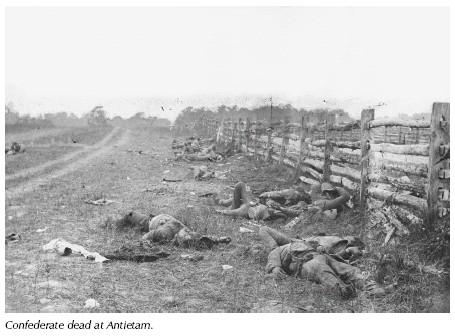

The guns fell silent. It was 5:30 p.m. More than 3,600 men lay dead on the field, a record that still stands for the largest number of Americans to die in battle in a single day. More than seventeen thousand others were wounded. The hours of darkness that night gave Lee the opportunity to use Boteler’s Ford to retreat into Virginia, but he did not. Instead he kept his army on the battlefield the next day, daring McClellan to renew the assault and contemplating an attack of his own until Jackson tactfully showed him the impracticality of the idea. With an additional day’s opportunity of trapping Lee’s woefully outnumbered army with its back to the Potomac, McClellan did nothing. In the previous day’s battle, he had committed scarcely two-thirds of his army, and he had nearly as many fresh troops left now as Lee had battle-weary men who could still stand on two legs. Yet McClellan remained convinced that somewhere behind the bluffs along the Potomac, another hundred thousand or so Rebels lurked, ready at any moment to swarm out and overwhelm his outnumbered Army of the Potomac. During the night of the eighteenth to the nineteenth of September, Lee reluctantly retreated across the Potomac into Virginia, marking the end of the campaign.

In military terms, the campaign had decided nothing. Lee’s army had marched into Maryland, and it had marched back out again. No territory or resources had changed hands for longer than the few days the campaign lasted, and the relative strengths of both sides had remained the same. At most these fifteen days in September had revealed the resilience of the northern soldiers in returning to battle and fighting hard despite that summer’s setbacks, and it had revealed the loyalty to the Union of the large majority of the citizens of western Maryland.

However, by forcing Lee to retreat across the Potomac much earlier than he had obviously planned, the Battle of Antietam had given Lincoln the victory he had been awaiting since July and with it the opportunity to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, thus opening a new chapter in the war.

7

LINCOLN TAKES NEW MEASURES

THE EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION

O

n September 22, 1862, in the wake of what had been at least a strategic victory at Antietam, Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. In it the president announced that one hundred days from that date, January 1, 1863, all slaves living in areas then still in rebellion against the United States would be henceforth and forever free. The Emancipation Proclamation changed the immediate goal of the Union forces in the Civil War but not its underlying issues. The war had from the beginning been about slavery. Rebellious southerners had launched the Confederacy for the purpose of spreading and preserving slavery, while Lincoln had led the North in fighting to preserve the Union and constitutional government. Now the war would become as explicitly a contest about slavery on the part of the North as it had been from the opening shot, and before, on the part of the South.

The Emancipation Proclamation would also change the way the war was fought. Once it was issued, or at least once Lincoln’s January 1 deadline had passed, there could be no more thought of conciliating the South. The trend to hard war, with southern civilians feeling all of the harshness conquered citizens usually do feel in a civilized war, would continue apace. Most white southerners would fight to the bitter end to preserve slavery and the system of white supremacy for which they thought it the only protection, and they would fight with renewed bitterness and intensity. Once the Union began recruiting black troops the following year, Confederate troops perpetrated a number of atrocities and massacres against them when they had opportunity. The war was becoming even more brutal than it had been up to now.