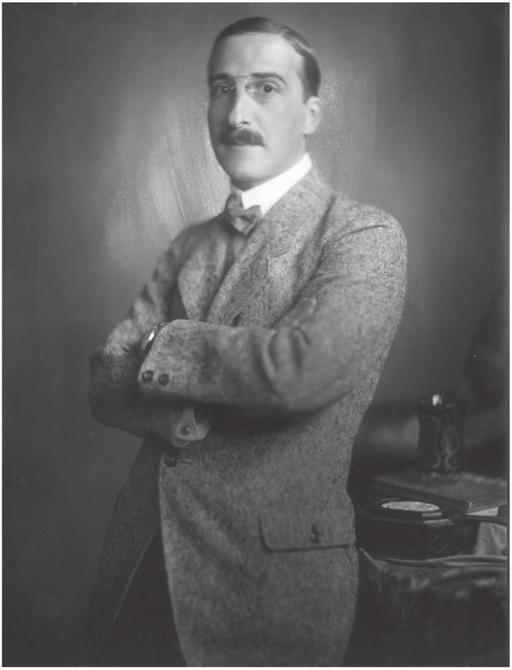

Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig (30 page)

Read Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig Online

Authors: Oliver Matuschek

Friderike did her best to counter the pessimism of the two Zweig sons by persistently emphasising the good news. When she was in Vienna the following year she visited her in-laws and wrote to her “Dear Stefferl” that they were very well, that his father was now using a wheelchair, but was also able to walk a few steps. She went on:

Both parents are very loving towards me, both pay me all kinds of attentions (it would make you blush). Papa even kissed my hand when I was leaving, and is really sweet in every way. [ … ]

I wasn’t expecting it, but everything here is peace and harmony, as never before. Is it the effect of the summer break, or just the fact that Alfred’s agitation, well-meant though it is, has not been picked up by your parents!?

She had something else to tell him. Her comment “Papa is very pleased about Stefanie”

27

is a reference to the news that Alfred Zweig had just brought his partner Stefanie Duschak home to meet his parents. The couple had probably known each other for some time, and they married on 2nd May 1922—which meant that Friderike would now have to compete for the favour of her in-laws.

Now that his professional life was up and running again in Salzburg, Zweig could not complain about a lack of correspondence. As well as dealing with his normal business correspondence and answering letters from his readers,

he received quite a few letters of encouragement from people he respected. Sigmund Freud continued to take a close interest in every new publication that Zweig sent him.

Drei Meister

, a book of essays on the three novelists Balzac, Dickens and Dostoevsky, was no exception, and Freud responded with a detailed critique. He was full of praise for the pieces on Balzac and Dickens, but had some reservations about the Dostoevsky essay. Coming from such a distinguished quarter, Zweig was prepared to tolerate criticism.

The post also brought him a letter from publisher Samuel Fischer offering Zweig the editorship of the

Neue Rundschau

, which, together with its predecessor titles, had now been appearing under the Fischer imprint for some thirty years. Zweig declined however, fearing that the task of running this journal with the commitment that the job required would take up too much of his time. He still had too many projects of his own awaiting his attention, not to mention writing regular articles for all manner of newspapers and magazines (including the

Neue Rundschau

for some years now) and major publishing projects like

Bibliotheca mundi

, which he did not want to lose sight of. If he took on permanent editorial responsibilities on a monthly journal he would probably have had to abandon many of his future plans for good. In principle Zweig had no objections at all to a permanent working relationship with a publishing house—in his case, Insel Verlag—but he had to have time to himself and the freedom to deliver manuscripts when it suited him, and not to let himself get too bogged down in day-to-day business matters.

In November 1921 he travelled to Berlin. He planned to spend two weeks in the big city, taking in some theatre and concerts and sampling the social life—the latter only in very small doses. He met many old acquaintances, including Camill Hoffmann, Maximilian Harden and Samuel Fischer. Despite interesting encounters and fascinating conversations, Zweig was soon overcome by the malaise that exposure to city life in general—self-inflicted on this occasion—was apt to bring out in him. Added to this was a growing aversion to the particular ambience of Berlin, which is articulated in one of his first letters from there, addressed to “Dear Fritzi”: “Berlin

profondément antipathique

. There are cities that just can’t cope with standing still. Seven years on I’m appalled by the faded glory of the cafés and beer halls, while on the other hand you don’t see any smart new places opening up either. There’s something stale and rancid about the whole life of the city, even though the streets are livelier than ever. And how ghastly the people are—my God, how ghastly!” But Zweig was still in reasonably good spirits, and he managed to inject a little local colour into the concluding

sentences of his report to Friderike: “I think I have said it all. But you are like the lady I heard here yesterday in the telephone box next door, who ended her conversation with the words: ‘Now tell me something nice, my little one’. I suppose I should tell you something nice too, my little one—so here goes: hugs and kisses from your so far still faithful Stefzi.”

28

The high point of his visit to Berlin was a reunion with Walther Rathenau, who had in the meantime been appointed by the government to conduct key negotiations about war reparations and reconstruction, and who would soon afterwards be promoted to the position of Germany’s Foreign Minister. As on the occasion of their first meeting some years previously, Rathenau managed to squeeze the meeting into his already overcrowded schedule. In

Die Welt von Gestern

Zweig writes:

With some hesitation I called him in Berlin. How could I think of bothering a man who was busy shaping the destiny of our time? “Yes, it’s difficult,” he told me on the telephone, “these days even friendship has to be sacrificed to my work.” But with his extraordinary ability to make use of every minute he promptly devised a way of meeting up. He had to drop off a few visiting cards at the various embassies, he said, and since he would be taking the car from Grunewald and driving around for half an hour to do this, the simplest thing would be for me to come to him and we could then talk in the car for that half hour. [ … ] I didn’t want to miss this opportunity, and I think it did him good too to have a chance to talk properly to someone who was not politically involved, and who had known him as a personal friend for many years.

On the subject of Rathenau’s appointment as Foreign Minister Zweig added: “He was fully aware of the twofold responsibility he bore because he was a Jew. There can have been few men in history who have taken on a challenge with so much scepticism and so full of inner misgivings, knowing that the problem could not be solved by him but only by time—and fully aware of the personal risk to him.”

The two men would never meet again, for a little over six months later the German Foreign Minister was assassinated by elements on the far right. While driving in an open car from his villa in Grunewald to the Foreign Ministry, Walther Rathenau was shot and killed. Looking back on this event and its dire consequences in

Die Welt von Gestern

, Zweig once again draws on his own experience as a near eye witness to heighten the drama:

Seeing the photographs later, I realised that the road we had travelled together was the very one where the murderers lay in wait, not long afterwards, for the same car: it was only by chance, really, that I was not on the scene to witness this historically fateful act at first hand. So I felt a more directly personal and emotional connection with the tragic episode that marked the beginning of Germany’s—and Europe’s—calamity.

29

The mood of unrest in Germany was making Zweig increasingly watchful and suspicious. This time he had made early arrangements to avoid the summer festival season, planning a trip to the North Sea that would get him away from Salzburg for a good two weeks from the middle of August. His itinerary would take him via Munich and the obligatory visit to his publishers in Leipzig to Hamburg and finally on to Westerland on the island of Sylt. Victor Fleischer had suggested a change of destination, proposing that they spend some time together on Langeoog. But Zweig had evidently heard a report of anti-Semitic demonstrations taking place on this same East Frisian island. Just a few days after the assassination of Rathenau he wrote to his friend Fleischer and rejected his alternative travel suggestions, offering his own view of contemporary events and a disturbing forecast of what was to come:

I can’t bear to be anywhere near these Pan-German louts. Give me Frankfurt Jews, give me Norderney any day, rather than the cast of mind that could murder a man like Rathenau and then send anonymous letters to his seventy-five-year-old mother, mocking her even as she mourns the death of her only son. These people are the scum of the earth! And the saddest thing of all is that they will succeed in their aims once again—just as they got their U-boat war and succeeded in prolonging the war itself, they will plunge us all into a new war. They’ll stay safely back behind the lines again while the young lads are mown down: in France the whole country is on a war footing. All the signs are there. Things are going to get rough.

So L[angeoog] is not on. I’m not going to excuse myself and be “tolerated”, especially when I’m paying good money. I’d rather go to a spa with 700,000 Galician Jews! I can do without that—I’d rather go to Marienbad or Italy, if I can’t find the right thing here. If I’m breathing the same air as them, they’re stinking out the whole of nature for me—I feel for this lot what I normally don’t allow myself to feel—utter hatred.

30

NOTES

1

Zweig 1922, p 9.

2

Stefan Zweig to Carl Seelig, undated, early February 1920, ZB Zurich, Ms. Briefe Zweig.

3

Stefan Zweig to Anton Kippenberg, 27th January 1919. In: Briefe II, p 263.

4

Zweig 1919.

5

Stefan Zweig to Friderike Maria von Winternitz, undated, probably 3rd April 1919. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 88.

6

Stefan Zweig to Carl Seelig, 7th April 1919, ZB Zurich, Ms. Z II 580.183, fol. 1r.

7

Stefan Zweig to Carl Seelig, undated, early 1919, ZB Zurich, Ms. Z II 580.183a.

8

Alfred Zweig to Richard Friedenthal, 22nd September 1958, Zweig Estate, London.

9

Prater questionnaire, SLA Salzburg.

10

Zweig F 1947, p 171.

11

Zweig F 1947, p 166.

12

Stefan Zweig to Marek Scherlag, 22nd July 1920. In: Briefe III, p 27.

13

Stefan Zweig to Carl Seelig, 2nd December 1919, ZB Zurich, Ms. Z II 580.183, fol. 6v.

14

Stefan Zweig to Carl Seelig, 19th March 1920, ZB Zurich, Ms. Z II 580.183a.

15

Stefan Zweig to Fritz Adolf Hünich, 15th December 1919, GSA Weimar, 50/3886, 2.

16

Stefan Zweig to Friderike Maria von Winternitz, undated, probably 27th January 1920. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 109.

17

Stefan Zweig to a wedding guest (his best man?), undated, probably 27th January 1920, copy in the archive of S Fischer Verlag.

18

Friderike to Stefan Zweig, 30th January 1920. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 109 ff.

19

TM Tagebücher 1918–1921, entry for 10th February 1920, p 376.

20

Stefan Zweig to Carl Seelig, 5th July 1920, ZB Zurich, Ms. Z II 580.183a.

21

Stefan Zweig to Insel Verlag, 19th September 1921, GSA Weimar, 50/3886, 3.

22

Stefan Zweig to Insel Verlag, 20th October 1921, GSA Weimar, 50/3886, 3.

23

Friderike and Stefan Zweig to Victor Fleischer, 22nd August 1920. In: Briefe III, p 26 f.

24

Stefan to Friderike Zweig, 11th June 1920. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 111 f.

25

Postscript added by Victor Fleischer to a letter from Stefan to Friderike Zweig, 20th October 1920, SUNY, Fredonia/NY.

26

Friderike to Stefan Zweig, 24th October 1920. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 117 f.

27

Friderike to Stefan Zweig, undated, probably 2nd November 1921, SUNY, Fredonia/NY.

28

Stefan to Friderike Zweig, 18th November 1921. In: Briefwechsel Friderike Zweig 2006, p 125 f.

29

Zweig GW Welt von Gestern, p 354 ff.

30

Stefan Zweig to Victor Fleischer, 29th June 1922. In: Briefe III, p 70 f.

Stefan Zweig 1920

For the second time I have read in some statistics published in Berlin that my books are among the top-selling titles (Berliner Tageblatt). That may be disagreeable for Insel, because I have to pester you so often for new editions, but not for me.

1