Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig (33 page)

Read Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig Online

Authors: Oliver Matuschek

A

LFRED

Z

WEIG

P

RESIDENT OF

M Z

WEIG

AG

O

BER

-R

OSENTHAL BEI

R

EICHENBERG

—V

IENNA

Since 1919 he had been a Czech citizen. When the former multinational state of Austria-Hungary had broken up into a number of different countries, residents had had to opt for their preferred citizenship. Years later Alfred’s choice would prove to be very helpful. With the restructuring of the firm he had received a contract as company president for life, which gave him an annual salary of over 400,000 Czech

kronen

plus a pension for his later years and generous provision for his widow in the event of his death. His managerial skills and his shareholding in the company enabled him to maintain a very comfortable lifestyle through all the financial crises. He could afford to hang the walls of his apartment in Vienna with paintings by Dutch masters, and he enjoyed travel as much as Stefan, although he preferred destinations closer to home. In the 1920s and 30s he and his wife generally took several holidays a year in Switzerland and Italy.

Stefan accepted a seat on the firm’s board of directors, on condition that he was not involved at all in business or administrative matters. He was a silent partner in every sense of the term, fully recognising that his advice would be of little use to the business. (He had once written to Insel Verlag: “My talents for book-

keeping

are minimal, and I deliberately don’t cultivate them in order to keep my talent for book-

writing

unadulterated.”

16

) Stefan also received the same number of shares in the company as Alfred—7,875 shares each, at a face value of four hundred Czech

kronen

—giving each brother a forty-five per cent stake in the company. The remaining ten per cent of the business, in the form of 1,750 shares, was owned by the Bank für Handel & Industrie in Prague.

While Alfred spent a lot of his time at the weaving mill’s sales outlet in Vienna, the key positions of responsibility in Ober-Rosenthal were occupied by factory manager and company secretary Hugo Iltis, who had

been employed there for over thirty years, and company secretary Heinrich Stare, who at the time of his retirement in 1938 had worked for the Zweig family firm for fifty years. Stare also acted as trustee for the company shares owned by Stefan. Alfred and Stefan telephoned regularly to discuss any issues relating to their investments.

At Insel Verlag meanwhile a new series had been created as a vehicle for Zweig’s biographical essays. It was called

Die Baumeister der Welt

[

The Architects of the World

], and subtitled “Towards a Typology of the Mind”. The second volume in the series,

Der Kampf mit dem Dämon

[

Battling with Demons

], appeared in 1925, containing the essays on Hölderlin, Kleist and Nietzsche. The book began with the following dedication: “This triad of artistic endeavour is dedicated to that penetrating intellect and inspirational thinker, Professor Dr Siegmund [

sic

] Freud”. Freud’s letter of thanks arrived in Salzburg in mid-April, to which Zweig then responded in his turn, saying that it was thanks to Freud that writers could now approach biographical studies without misplaced coyness and enter into the emotional world of their subjects without feelings of prudishness—which were precisely the qualities that Zweig’s growing readership liked about his writing.

In the summer he travelled with Rolland to Weimar, where they visited the Nietzsche Archive together. Contrary to Zweig’s expectation, Elisabeth Foerster-Nietzsche, the philosopher’s sister, declared herself very pleased with the essay he had published about her brother. A visit to his publishers in Leipzig followed, where Zweig met the young writer Richard Friedenthal. He liked him immediately, and kept in close touch with him over the coming years. Before leaving Leipzig Zweig and Rolland witnessed a mass demonstration of young people organised by right-wing groups. The only good thing about this frightening spectacle, as Zweig wrote bitterly in a letter to Friderike, was that as a man of goodwill one must also be acquainted with the sort of dangers that are brought home to one in this unsavoury way.

This year’s escape from the Salzburg Festival did not take him to distant parts, but only as far as Zell am See, within easy reach of home. As in previous summers he feared the influx of hordes of people to Salzburg. This was another area of disagreement in the Zweig household. Stefan supposed, quite rightly, that large numbers of exhausting visitors, who nonetheless could hardly be turned away, would beat a path to his house, either to take up his valuable time or to ask, more or less unashamedly, if he could use his influence to get them tickets to performances at the last minute. Friderike on the other hand went to a number of performances

herself and liked to play the literary wife on the sidelines. She was not at all averse to having visitors in the house, and she tells us herself that while Stefan was away she even made the garden available as a campsite for Festival-goers from India, who for religious reasons did not want to stay in a hotel under whose roof “unclean food” was prepared. As for Stefan’s suggestion that they put up an inscription on the wall of the house beneath the sundial—

Die Sonne hält nur kurze Rast

Nimm Dir ein Beispiel, lieber Gast

[Right briefly does the sun here dwell

And so we say, dear guest, farewell]

—this was given very short shrift by Friderike.

17

The regular annual problem of coping with Salzburg in the summer was aggravated this year (and probably not for the first time) by a more deep-seated crisis that had descended upon Zweig. From his holiday home he wrote to Friderike:

Here I find myself more isolated than at almost any time, I don’t know anybody, either in the hotel or in the town—just Germans and Hungarians, not a single Viennese in sight—[ … ] I’m working and reading a little, nothing too much, or at least not while the weather was fine. The novella I am sketching out is uncommonly difficult, but then I am only interested in tackling complicated material now.

My depressive states have no real causes as such, neither in work (which is not so bad) nor in nicotine, which I’ve given up for a two-day trial period. It is a crisis of ageing, associated with an excessive clarity (for someone of my age): I don’t delude myself with dreams of immortality, know how relative all the literature is that I can produce, don’t believe in humanity, find too little to delight me. Sometimes something comes out of such crises, sometimes one just digs oneself in deeper because of them—but when all is said and done they are part of one’s make-up. [ … ] And our war-damaged nerves, they cannot be altogether repaired, the pessimism goes deep. I have no more expectations, it’s all the same to me whether I sell 10,000 copies or 150,000. The important thing would be to start something completely new, another kind of life, a different ambition, a different relationship to existence—to emigrate, and not just in the physical sense.

18

In the garden of the house on the Kapuzinerberg, from left: Stefan Zweig, Friderike’s daughters Suse and Alix von Winternitz, Friderike Zweig, and—lying under the chair—the family spaniel Kaspar

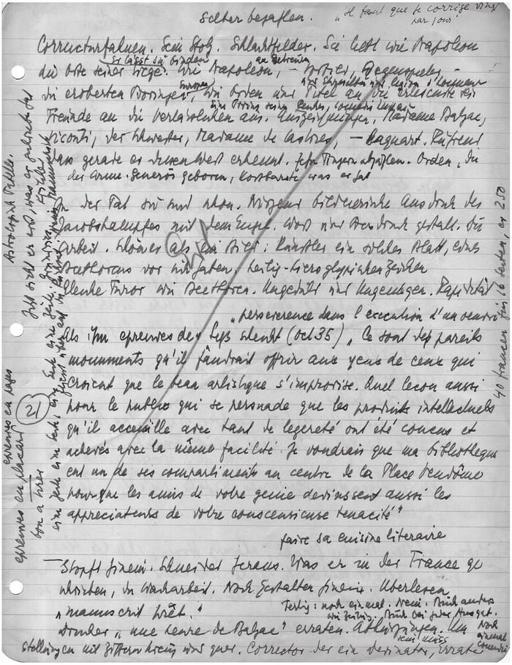

Sketches and notes by Stefan Zweig

Zweig was not yet forty-four years old when he wrote this letter. From now on he remarked more and more often that he was well past the midpoint of his life. He was able to banish his fear of ageing for a while with hiking tours and health cures, partly undertaken in an attempt to preserve a reasonably youthful appearance. But news such as that of the early death of his friend Ephraim Moses Lilien, which reached him shortly before his exodus to Zell am See, soon plunged him back into dark reflections on his own expectations for the future. “It has affected me deeply, he was [ … ] only a few years older than me, and a lot stronger, a dear companion of my youth, and it is painful for me to have to file his letters now under ‘Deceased’.”

19

By the end of the year his dark mood had improved again. In November he travelled to France. In Marseille he dined on bouillabaisse and other delicacies, was able to bathe in the sea despite the lateness of the season, and walked by day and by night with his newly acquired camera through the dingiest corners of the waterfront district, which he found endlessly fascinating:

I would like to write about a street like this, where next door to a cigar shop there’s a shop with four cows inside, and children playing with their own filth in the gutter outside, while the dirty linen of five hundred people is hung out from all four floors and blind beggars sing as they stumble about between the vegetables and the mangy cats. It stinks of the Orient: it’s no coincidence that incense was an oriental invention. But these wretched alleys lead straight into the city’s boulevards.

20

In good spirits he embarked there and then on a project he had long been planning. He wanted to adapt Ben Jonson’s early-seventeenth-century play

Volpone, or the Fox

for the German-speaking stage. Zweig later revealed that he had left the original text at home by mistake, forcing him to work from memory. In a very short time he had produced an adaptation of

Volpone

, subtitled

Eine lieblose Komödie in drei Akten von Ben Jonson, frei bearbeitet von Stefan Zweig,

which remains his greatest theatrical success to this day.

As 1926 dawned, Zweig had his sights set on another major project for the new year alongside his writing. At long last he planned to put his autograph manuscript collection into some sort of proper order and prepare a catalogue for the press. Other collectors had already done the same, and now Zweig—who looked upon his collection as an important part of his literary

work—wanted to follow their example. He engaged a young man called Alfred Bergmann to undertake the task, who was then working through the collection of Anton Kippenberg and preparing a new and enlarged edition of the complete catalogue with the assistance of Fritz Adolf Hünich.

But a few days before Bergmann was due to arrive the plan had to be shelved. When Friderike came home on 2nd March 1926 she found a note from Stefan: “Papa passed away suddenly at noon today, I am hoping to catch the 2.30 train, come yourself this evening and take a sleeper, first class.”

21

Moriz Zweig had died peacefully at the age of eighty. The family gathered in Vienna to bid farewell to him two days later in a small ceremony for the immediate family only. In line with family tradition, the announcement of his death and a brief obituary did not appear until after the funeral. A book of remembrance was opened for the deceased, containing a table that showed the day of commemoration for their late father, as calculated from the Jewish Calendar, for every year up until 1976. This document along with other family papers was held in safekeeping by Alfred as the eldest son. Stefan and Friderike returned to Salzburg soon after the funeral. His mother came to stay with them for a while, and they took her on excursions into the city and the surrounding countryside.

This year Stefan spent the summer in Switzerland, sketching out the plan for a new book. He wanted to study the life of Napoleon’s Minister of Police, Joseph Fouché, whose dark character provided much material for fascinating observations. While he was preparing the next in his extraordinarily successful series of biographies, Friderike began to wonder whether the time had not now come to publish a short account of Stefan’s own life. What she had in mind was not a comprehensive study, but a modest volume of around one hundred pages with an appendix containing an impressive bibliography of his writings and translations to date. Stefan’s friend Erwin Rieger seemed the obvious choice of author, especially as this arrangement would give Friderike—as she herself pointed out—a measure of control over the project: she wanted the book to focus primarily on Stefan’s work, and not so much on his private life.