Through the Tiger's Eye

K

ERRIE

O’C

ONNOR

has been making up stories since she was eight years old. She became a journalist at the age of eighteen and learnt how to ‘stick to the facts’, but was always tempted to sneak stories about talking animals into the newspaper. While working for ABC Radio, she made a series of documentaries about war in Eritrea. ‘It is the children who remain with me: brave, optimistic, damaged, hungry . . . and still ready to party.’

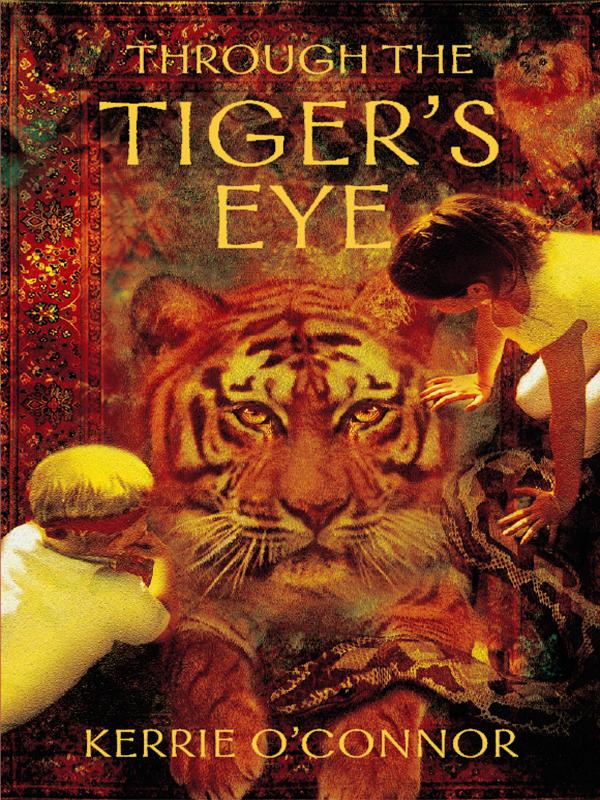

Through the Tiger’s Eye

, her first novel, draws on this experience, although it is set in a magical country where the jungle is thick and tigers still prowl.

Kerrie was born in the Year of the Tiger, and once (when she was a little girl) owned 21 cats. ‘I thought I was so lucky! It took me years to work out that we just couldn’t afford to get them desexed.’ These days she doesn’t live with any cats, much to the relief of the water dragons in her creek . . . but she still says ‘Hi’ if she meets one.

THROUGH THE

TIGER’S

EYE

KERRIE

O’CONNOR

First published in 2003

Copyright © Kerrie O’Connor 2003

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

The Australian Copyright Act 1968

(the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web:

www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

O’Connor, Kerrie, 1962– .

Through the tiger’s eye.

For children.

ISBN 1 86508 538 3.

1. Rescues - Juvenile fiction. I. Title.

A823.4

Designed by Jo Hunt

Set in 11.5 on 15 pt Berkeley by Midland Typesetters

Printed by McPherson’s Printing Group

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to my parents,

my partner and my son; and to Joan Yule and

Jim McCall, who, confronted with a tiger cub

in the classroom, opened the cage . . .

Thanks to all those who read early and (very) late drafts: Michael, John, Fay and Helen Panckhurst; Mary, Alice, the two Karls and Carmel; Susanne, Vuli and Bheki; Felix and Ruth (who jumped up and down when the phone call came); Hilary, Lila and Natalie; Jenny, Mark, Timiny and Bearyn; Alison, Peter, Heather, Duncan, Angus and Erica; Fiona, Dave, Tom, Xanthe and Jelly Bean; Anne and Jessie; Matilda, Sara and Kevin; Anita; Andrew Stevenson; Di Fitton; Sarah and Henry. For their patience, I thank Oscar, Sam and Gabriel, and for their sharp eyes, Claire Gerson, Ros Walker and Judy Gill, who always said it would be done.

Special thanks to skilled fellow travellers Erica Wagner and Sarah Brenan, who trimmed without torment.

Contents

12 The Octopus Information Exchange

In the still of a summer night, no one noticed a handsome ginger cat wriggle through the kitchen window of an ordinary house in Kurrawong. The cat showed no interest in the remains of a peperoni pizza on the table, but padded purposefully across the hall, through a doorway, into the bedroom of a sleeping twelve-year-old girl with long dark hair. The cat leapt lightly onto the bed and gazed intently at the girl. She didn’t stir, nor did the puppy on the end of her bed.

But Lucy’s dream changed.

One minute she was playing dream soccer on a flashing dance floor; then the driving bass and techno beat became . . .

Gunfire!

A smiling soldier in a brown uniform raises his rifle triumphantly to the sky. On his shirt is the image of a black bull, with red eyes and yellow horns.

Seconds stretch silently . . . and explode. Children scream, run for their lives, run from brown uniforms and guns.

In this sea of panic a little girl sails toward Lucy, calm in the eye of the storm. She has black curls, a glorious pink-and-gold dress hemmed in snowy white lace, shiny black shoes. She is staring right into Lucy’s eyes. Her eyes are black. Her little hand reaches for Lucy’s. Her skin feels like paper.

A woman glides across the grass towards them.

The smiling soldier shouts at her, but she is already squeezing a scrap of paper into the little girl’s free hand. The tiny fist clenches shut.

The woman’s black eyes are burning into Lucy’s.

‘My little girl is yours now. You must look after her until you find —’

Rough hands pull mother and daughter apart. Over the shoulder of the brown-shirted soldier who carries her, the little girl’s black eyes hold Lucy’s. In the midst of screams and chaos, she hasn’t made a sound.

‘Is that it?’ Dread wriggled out of Ricardo’s mouth like a worm. ‘We can’t live

there

. . .’ he said.

He wanted to say ‘because it’s a dump,’ but Mum would get upset. Again.

Lucy didn’t care, though.

‘It’s a dump, Mum! Retardo’s right for once. It’s not even worth getting out of the car.’ Before Mum could say, ‘Don’t call your little brother names!’ Lucy wound up the window.

Why did Mum want to look at the worst house in Kurrawong?

You couldn’t

get

any further away from the beach. It was way up in the bush, at the end of a lonely dirt track that snaked up the escarpment. The escarpment looked like one of those giant slippery water slides at a fun park, except that it was a couple of kilometres long and you’d slide right into the Pacific Ocean. It was covered in rainforest and stretched as far as you could see in either direction. Ten thousand kids could hold hands and slide down, if they didn’t mind getting wedgied on giant gum trees.

At the very top, stretching forever, was a jagged wall of rock.

That was the end of Kurrawong. The only things that escaped over those cliffs had wings. And Lucy was no angel.

Below the cliffs, hidden in a dense jungle of towering green, was the last house in town.

The last place Lucy wanted to live.

A real dump.

The sign nailed to the fence had said ‘To Let’ until someone scribbled an ‘i’ between the words. Probably the last loser who drove all the way up here for nothing. The verandah sagged in the middle as though a giant bum had sat on it. Faded paint hung off the walls in strips, and the roof was rusty brown. Whoever had nailed up the ‘Toilet’ sign had found the only bit of fence still standing. No way would it keep in a hyperactive puppy called T-Tongue.

The grass was long and the roses had gone psycho, twisting all over a wonky archway above the front gate. They were probably holding it up. A gang of red and green parrots landed on the crooked verandah rail. Great, parrot poop, something else for Ricardo to step in. There was a shriek overhead and a gang of white cockatoos divebombed a gum tree, yellow crests flaring. Just what a family needed, cockatoo crap.

Mum nervously opened the driver’s door.

‘Lucky . . .’ she began, but Lucy jumped in furiously.

‘Don’t call me Lucky. I’m not lucky. If I was lucky we’d still be living at the beach and we wouldn’t have to rent a house at all. If I was lucky we’d still be living —’