Tiny Dancer (38 page)

When Peter and Rebecca decided to take Zubaida in, they did it fully aware that they would be pilloried in the media if their gamble on Zubaida’s behalf failed in some way. But the compelling force that seemed to congeal around her was already underway in their lives. The part of her journey that led through Peter’s career, their home, and their hearts was something that had to happen.

Rebecca found that in Zubaida’s absence, the process of keeping in touch with her and helping to guarantee her a chance in life also served to keep Rebecca motivated to continue working on behalf of Zubaida’s Foundation, as well as the Children’s Burn Center.

At the end of June, 2004, she gave birth to a healthy and beautiful daughter, and the parenthood that she and Peter had desired for so long finally arrived to stay. They named their girl Alexis, and began a sustained campaign to pack the email addresses of everybody that they knew with pictures of Alexis doing a hundred variations on being a perfect baby girl.

IN THE END—

any miracle that may have taken place in this story only began with Zubaida’s surgical transformation; it moved through the transformation of her heart from its trapped condition in a prison of despair, through the return to its former state as a beating channel for the music she loves, and ultimately led her to an entirely different way to live her life as a young woman in the newly emerging society just beginning in her homeland.

The unyielding grasp that she maintained on life from the moment that the fire took her compels the question of how hard we are grasping our own lives as they speed by us. If we were somehow boiled down to our most basic desire to live, as Zubaida was boiled down to her love for rhythm and music, what essential things would define our own struggle to exist?

There are still levels of humanity and decency that are recognized all over the world. By engaging one another at that level, beyond the reach of armies and politics and religious debates, we may stitch together whatever future lies ahead for us. If Western society is not witnessing its own implosion, as some people see its plight today, then we are left to ask ourselves specifically what human asset it is that might prevent us from going in that grim direction.

People of every political persuasion already carry the sinking feeling that military action can’t do it, and that globetrotting freelance murder can’t do it, and that the passing of laws won’t do it, either. Religions have never come close to doing it and politicians don’t even know where to start.

But everyone who has followed Zubaida’s journey knows how. They have watched her “hopeless” case get carried by one concerned hand after another, across barriers of race, language, religion, politics, the dangers of professional losses, personal embarrassment, and opportunistic lawsuits—all Perfectly Good Reasons why nobody should have gotten involved.

The players in her story were struck by the need to help her because, like the rest of us, they are out there in the world among the Others, each in their own way. As the Others were described to Zubaida, they were people with no respect for another’s values and the strong desire to spread toxic energy. A person may sidestep the despair that the Others work to inflict, and perhaps dodge the scarring effect of their cynicism, but it takes a steady force of will to go on and carve out a full life despite their debilitating presence. Since the Others are never going to disappear, we are left to build those full lives in spite of the recurring images and ideas of failure and conflict that the Others are always eager to cast onto us.

Leaving them behind only requires movement of the mind, not the body. It involves living out the personal, day-to-day reality of what to do about the human condition.

That full life calls out to us because we are all aware of places where we can do great good even when we have Perfectly Good Reasons not to get involved. When and if we step up, we do so knowing that in the long run this is simply how we make things better for ourselves.

The ride that we take when we follow Zubaida’s long journey leads us away from a storybook mirror showing her restored reflection. It leaves each one of us alone in front of an internal mirror, challenged by our own.

Photo Gallery

Zubaida and her best friend, Emily

This is how Zubaida looked when she arrived in Los Angeles.

The one-year transformation

Robert Frame (in black vest) helps Zubaida’s father, Mohammad, deal with the Americans’ baffling love for signing pieces of paper.

Zubaida with Peter Grossman and his father, renowned burn surgeon Richard Grossman

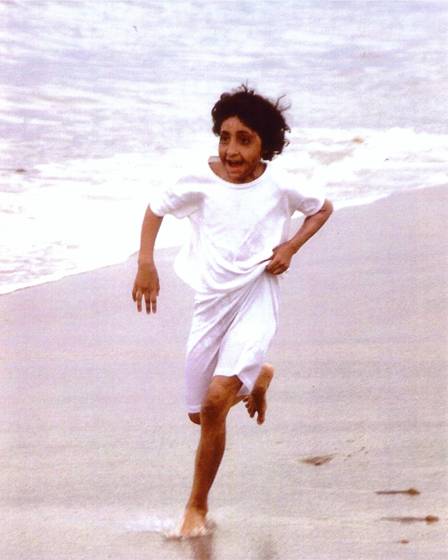

The return of the tiny dancer

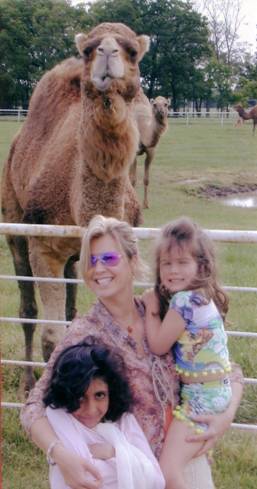

Zubaida and her friend with Rebecca Grossman and a secret admirer

The father-daughter dance at school cemented her relationship with Peter Grossman as “Dad.”

Things get better.

There are also good days.

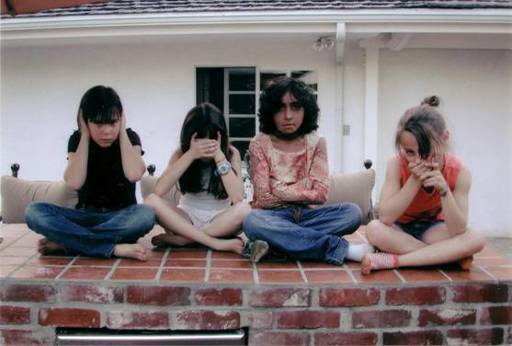

Hear no evil… see no evil… I’m not playing… speak no evil