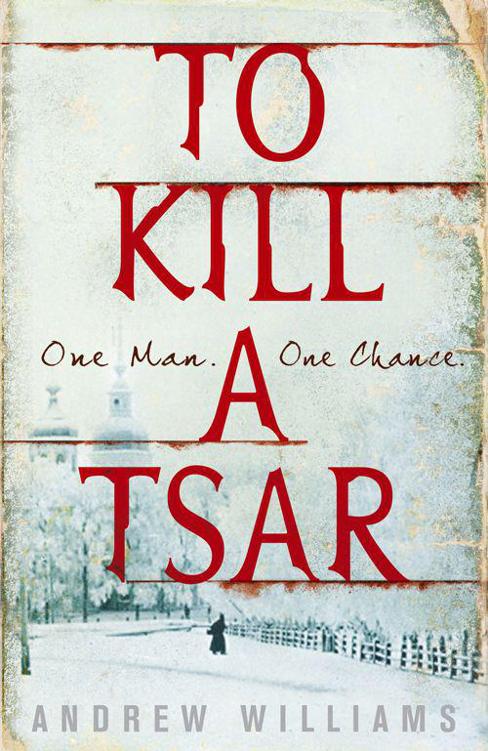

To Kill a Tsar

Authors: Andrew Williams

Also by Andrew Williams

FICTION

The Interrogator

NON-FICTION

The Battle of the Atlantic

D-Day to Berlin

ANDREW WILLIAMS

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by John Murray (Publishers)

An Hachette UK Company

© Andrew Williams 2100

The right of Andrew Williams to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher.

All characters in this publication – other than the obvious historical figures – are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

Epub ISBN 978-1-84854-346-1

Book ISBN 978-0-7195-2391-5

John Murray (Publishers)

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

For Lachlan and Finn

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS

. . . [the] requirements of the constitution consisted: first, in the promise to devote all one’s mental and spiritual strength to revolutionary work, to forget for its sake all ties of kinship, and all personal sympathies, love and friendships: second, to give one’s life if necessary, taking no thought of anything else, and sparing no one and nothing . . . these demands were great, but they were easily fulfilled by one fired with the revolutionary spirit, with that intense emotion which knows neither obstacles nor impediments, but goes forward, looking neither backward nor to the right nor to the left . . .

Vera Figner on the constitution she upheld as a member of the executive committee of The People’s Will

2 APRIL 1879

I

ce is scraped from the carriageway in readiness, but it is still treacherous and the tsar must tread with care.

At eight o’clock the guard at the commandant’s entrance to the Winter Palace came smartly to attention and the doors swung open for the Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias. A tall man with the bearing of a soldier, Alexander II was in his sixtieth year, handsome still, with thick mutton chop whiskers and an extravagant moustache shot with grey, a high forehead and large soft brown eyes that lent his face an air of vulnerability. His appearance was greeted by a murmur of excitement from the small crowd of the curious and the devout waiting in the square. On this iron grey St Petersburg morning, the islands on the opposite bank of the Neva were almost lost in a low April mist, and tiny drops of rain beaded the tsar’s fur-lined military coat and white peaked cap. As was his custom, he walked alone but for the captain of his personal guard who followed at several paces. Head bent a little, his hands clasped behind his back, a brisk ten minutes to clear his thoughts before the meetings with ministers and ambassadors that would fill the day.

From the north-east corner of the square he made his way into Millionnaya Street and on past the giant grey granite Atlantes supporting the entrance to the New Hermitage Gallery his father had built for the royal collection. Then to the Winter Canal and the frozen Moika River, its banks lined with the

yellow and pink and green baroque palaces of the aristocracy. A carriage rattled along the badly rutted road, sloshing dirty melt water across the pavement and the tsar’s cavalry boots. At the Pevchesky Bridge, he turned and the square lay open before him again, the stone heart of imperial Russia: to his right the Winter Palace, and to his left the vast yellow and white crescent-shaped building occupied by the General Staff of his army. A score or more of his people stood at the corner of this building, stamping their feet, blowing vapour into balled hands, waiting for a glimpse of their ‘Little Father’. From this group, a tall young man in a long black uniform coat and cap with cockade stepped forward and walked towards the tsar. His features were half hidden by the upturned collar of his coat and a thick moustache. He stopped beneath one of the new electric street lamps at the edge of the square and, as the tsar approached along the pavement, gave a stiff salute. Something in his demeanour, in his wide unblinking eyes, caught and held the tsar’s gaze and brought to his mind a childhood memory of a bear he had seen cornered by hunting dogs. He walked past but after a few steps this uneasy thought made him turn to look again.

In the young man’s hand was a revolver. Struggling to balance it. Struggling to aim. Barely more than an arm’s length away. A flash. Crack. Flakes of yellow plaster splintered from the wall on to his shoulder. Crouching, spinning, the tsar began to run, weaving like a hare, to the left then to the right, and as he did so time wound down until it was without meaning. Shouts and screams reached him as a muffled echo at the end of a long tunnel. He could hear distinctly only the pounding of his heart and again the sharp crack, crack of the revolver. It was as if there were only the two of them in the square: Alexander, the Emperor of Russia, stumbling towards his palace, and a young man with a gun in his trembling hand. He was conscious of the short shaky breaths of the assassin and the scuffing of his boots

on the setts behind him. Crack. A shot passed through his flapping greatcoat and he swerved to the left again. On and on the madman came with his arm outstretched. Another crack, and a bullet struck the ground a few feet in front of him. Was this an end to joy, an end to love? Breathless with fear, lost in this tunnel. For what purpose? Who could hate him so much?

Then someone was at his side, a hand to his elbow, and time seemed to turn again.

‘Your Majesty—’

Shaking like a leaf in an autumn gale.

‘I . . . I am all right.’

It was just a few seconds. That was all. Slowly, the tsar turned to look over his shoulder. His pursuer was on the ground, curled into a tight ball, kicked and punched by the police. The revolver lay close by. Something obscene. Cossack guards were running from the palace and a calèche was drawing to a halt a few yards from him. An old woman, tightly wrapped in black rags, had fallen to her knees and was rocking a prayer of thanks. She clutched at his coat as he brushed past.

‘Thank God! Thank God!’ And she crossed herself again and again.

As he stepped into the carriage there were angry shouts. The tsar turned to see the assassin dragged senseless to his feet. He did not notice the young woman with dark brown hair who was walking away from the gathering crowd. No one paid her any attention. She walked with a straight back and a short purposeful stride. Her clothes were faded and a little old-fashioned but she wore them well. At the edge of the square she stopped for just a moment to pull an olive green woollen shawl over her head and across her nose and mouth. Her face was hidden but for her eyes, and they were pale grey-blue like the sky on a summer afternoon or the colour of water through clean ice.

At the end of the Nevsky Prospekt she took a cab. Her driver

guided his horse with great care, for the city’s main thoroughfare was bustling with trams and carriages, merchants to the Gostiny Dvor trading arcade, uniformed civil servants to their ministries. The droshky came to a halt just before the Anichkov Bridge. The young woman paid the driver with a five kopek coin, then walked across the bridge towards the pink and white palace on the opposite bank of the Fontanka River. At the first turning to the right beyond it she paused to look back along Nevsky, then, lifting her skirt a little to lengthen her stride, she hurried into the lane. Sacks of wood were being unloaded from a wagon, and she passed an old man pulling a barrel organ, its mechanism tinkling in protest. A small boy in a red shirt was playing on a step with a kitten and a yard keeper scraped hard ridges of ice from the pavement in front of his building. Before a handsome blue and white mansion, she glanced up and down the lane then stepped forward to ring the door bell.

The dvornik, who was paid to fetch and carry for the building, showed her up to an apartment on the second floor. The door was opened by a short, plump man in his late twenties, well groomed in a sober suit and tie. He had a round fleshy face, a neat beard and black hair swept back from a high forehead.

The dvornik gave a little bow: ‘A lady to see you, Alexander Dmitrievich. She won’t give her name.’

Alexander Dmitrievich Mikhailov must have recognised his visitor, though he could see only her eyes, because he stepped aside at once to let her into the apartment. Three more young men were sitting at a table in front of the drawing-room window. She collapsed onto a chair beside them.