To Kingdom Come (11 page)

Authors: Robert J. Mrazek

He continued to cradle the injured man in his arms until an ambulance arrived. After Liewer was on his way to the base hospital, Kenneth Rood approached Andy and told him he couldn’t fly the mission. Although the eighteen-year-old was physically uninjured, his hands were shaking. Andy told him it was all right, and that he would ask for replacements for both men as soon as he got to the plane.

The rest of the crew was visibly nervous when Andy arrived at the hardstand and they saw his bloody flight suit. After telling them what had happened, he began his regular check of the airplane with the ground chief. He had just finished when the two last-minute replacements, Ralph Biggs and Guido DiPietro, arrived.

After welcoming the new men, Andy climbed into the cockpit and tried to relax for a few minutes. Although he didn’t consider himself religious, he knew that in a few hours they would be raining close to a thousand tons of bombs down on Stuttgart, Germany, and not all of the victims would be fire-breathing Nazis. Women, children, and elderly people would be killed, too. As he always did before a mission, he delivered a silent apology for the innocent lives that might be taken.

Far off to the left, he saw the flash of a flare gun above the Thurleigh control tower. It was the signal for the pilots to start their engines. There was no time to read a passage from the “Choric Song” of

The Lotos-Eaters

.

He pressed the starter button for the left outboard engine and heard the familiar whine as he injected a charge of fuel to prime it. The engine roared into life with an effusion of greasy smoke, and he began the same process with the inboard engine, closely monitoring the oil pressure and temperature gauges. He repeated the same steps with the third and fourth engines.

A second flare burst over the Thurleigh control tower. It was the signal for the Fortresses to taxi to the runway, forming into the takeoff line ordained at the premission briefing.

When the ground crew removed the wheel chocks from in front of the tires,

Est Nulla Via Invia Virtuti

began rolling slowly off the hardstand onto the perimeter apron. Beyond the left wing, Andy’s ground chief was walking alongside the plane, gazing up at him like an apprehensive father worried about his son’s first solo trip in the family car.

Andy gave him a reassuring wave, his fingers still sticky from Liewer’s blood.

Buckinghamshire, England

High Wycombe Abbey

Eighth Air Force Bomber Command

0430

For the operational planners at High Wycombe, the task of organizing a maximum-effort mission against Germany was akin to assembling a gigantic jigsaw puzzle in the sky.

Zero hour for the Stuttgart mission had been set at 0720, the precise moment when all sixteen bomb groups participating in the attack on Stuttgart were expected to be in their respective positions in the twenty-mile train of bombers, each squadron in its assigned position within a group, each group in its designated place within a multigroup combat box formation, each combat box formation in its assigned position within the two bombardment wings, the entire armada of heavy bombers ready to depart for the enemy coast.

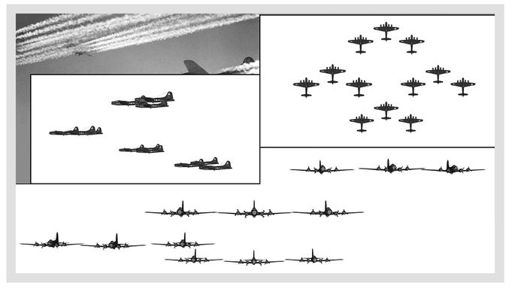

The combat box formations were critical to their chances for survival.

Colonel Curtis LeMay, who now commanded the Fourth Bombardment Wing, had created the concept of the combat box after flying a number of missions as commander of the 305th Bomb Group in 1942. It was as important to the development of the modern air war against Germany as the creation of the British square had once been in defending against a French cavalry charge.

LeMay’s combat box formation began with an individual bomb group, which for a maximum effort consisted of twenty-one Fortresses divided into three squadrons, with the lead squadron out in front, the high squadron following closely behind and to the right at a slightly higher altitude, and the low squadron tucked in behind and beneath the lead squadron on the left.

LeMay’s multigroup box formation utilized this same configuration on a larger scale. It typically consisted of three bomb groups, with the twenty-one planes in each group flying in the same staggered formation. The box was stacked by altitude, with the lead group in front, the low group below it, and the high group above it.

If the pilots were able to maintain a tight formation, the LeMay combat box created the maximum opportunity for massing the combined power of the Fortresses’ .50-caliber machine guns in interlocking fields of fire.

The staggered formation in the combat box also contributed to better bombing accuracy. Once over the target, the groups were able to release each plane’s bomb payloads in a concentrated pattern without endangering the Fortresses flying at lower altitude.

For the Stuttgart mission, which entailed the largest force to ever be sent against a target deep inside Germany, the assembly of the air armada in the skies over southern England was a mission in itself.

If all went well, it would take nearly two hours to put the train of bombers together. Since it would also be the longest mission ever undertaken, conserving fuel would be essential. It was vital that the assembly take place smoothly.

At the sixteen American air bases near medieval English villages like Bury St. Edmunds, Thorpe Abbotts, Molesworth, Grafton Underwood, Thurleigh, and Knettishall, the pilots of 338 Fortresses sat in their cockpits and watched the minute hands of their synchronized watches ticking down to the takeoff times that were set for them at the preflight briefings.

For the 388th Bomb Group in Knettishall, the first set of Frag (fragmentary) orders for the Stuttgart mission had arrived from High Wycombe on the group’s Teletype machines at 2240 the previous night. After officially logging them in, the operations staff began preparing briefing notes for the flight crews, including an updated weather advisory, a group formation plan, and the final order of takeoff for the group’s twenty-one bombers.

At exactly eighty-one minutes before zero hour, the 388th was to rendezvous with the 96th Bomb Group, which had been chosen to lead the air fleet. Their rendezvous would be at an altitude of forty-five hundred feet over the 96th’s air base at Snetterton Heath.

To avoid possible confusion with one of the other fifteen bomb groups circling in the skies, the lead pilot of the 96th group would signal its presence by firing two yellow flares. The lead pilot of the 388th would respond by firing one yellow and one green flare to indicate his arrival before taking up position behind the 96th.

The two groups would then proceed to climb in slow circles to an altitude of six thousand feet, where, at seventy-two minutes before zero hour, the 96th and the 388th groups would rendezvous with the 94th and 385th Bomb Groups over Fakenham, the ancient Saxon parish in Norfolk. Once those two groups were in tow, additional couplings of the bomber train would take place at seventy-five hundred feet, fourteen thousand feet, and seventeen thousand feet.

At 0720, the assembly of all sixteen bomb groups would hopefully be achieved as the lead Fortress in the 96th Bomb Group arrived over the coastal village of Dungeness, England.

Knettishall, England

388th Bomb Group

Second Lieutenant Ted Wilken

0515

In the gloom of breaking dawn, Ted Wilken and his copilot, Warren Laws, waited for the takeoff signal, still pondering everything that had already gone wrong that chaotic morning.

After the intelligence briefing, the two officers had arrived at their hardstand with the rest of the crew to learn that

Battlin Betsy

had been scratched from the Stuttgart mission due to radio communication problems. It created a brief stir of anger and disappointment.

Each B-17 had its own personality. There was something reassuring about a plane that was deemed to be lucky, and

Battlin Betsy

, which had been named for Ted’s wife, had been deemed just that. They hated not being able to fly in her, particularly on what might prove to be a tough mission.

The spare plane they were assigned was named

Patricia

, and its fuselage was adorned with the garish painting of a nude woman. Warren Laws didn’t appreciate the artwork. A serious young man, he was engaged to be married to his college sweetheart, Libby, and wasn’t comfortable with the lurid symbolism.

As they were doing their preflight checks, the crew’s regular bombardier, Gene Cordes, turned up ill, and Ted had to send for a last-minute replacement. When the new man arrived, it was too dark for Ted to even see his face as he disappeared into the nose compartment.

When Warren began checking over the equipment in the plane, he found that all their throat microphones were missing. Without them, there would be no way for the crew to communicate on the intercom. He dropped down through the forward belly hatch, jumped on his bicycle, and rode like the devil over to the squadron commander to report the problem. The commander proceeded to ream him out for failing to take care of his duties, and the flustered Warren never thought to tell him that they had just been assigned a spare plane.

He got back to

Patricia

with the throat mikes, only to discover that his parachute was missing from the pile of officers’ chutes that the enlisted men had brought out to the hardstand. Shortly before their scheduled takeoff, one of the crewmen located an extra chute, and Warren stowed it under the copilot’s seat.

With the preflight checks completed, Ted and Warren waited for the signal flare to start their engines. The two young officers had come a long way from the day they met back in Spokane when the crews were assigned. At first, they weren’t sure what to make of one another.

Ted was a blue-blooded socialite with famous friends, had prepped at Choate and attended Dartmouth, was a superb athlete, larger than life, a born leader. He made everyone in the crew feel like they were the luckiest guys in the Eighth Air Force to have him as their plane commander.

Warren was guileless and introspective. He was a good listener. He made friends by listening to people talk about themselves. When the crew got together for poker games at Ted and Braxton’s hotel suite, Warren would stand in the background with a big smile on his face sipping a soft drink. I play bridge, he said. Sometimes, he seemed to disappear within himself.

Although they hailed from different worlds, the two men had grown up close to one another, Ted in Bronxville, New York, and Warren in Stratford, Connecticut, a village founded by the Puritans in 1639 at the edge of Long Island Sound.

As a child, Warren suffered from asthma, and his mother became highly protective of him, not allowing the boy to enter grade school until he was seven. On Halloween, he was permitted to wear a costume, but not allowed to go outside. He would sit at the front window and watch the other children as they trick-or-treated down his block.

When he was nine years old, an event took place that changed his life.

It was the morning of May 20, 1927, and he was at home listening to the live radio coverage of Charles Lindbergh’s attempt to become the first man to cross the Atlantic alone in the

Spirit of St. Louis

. Warren could hear Lindbergh gunning the plane’s engine in the background before he took off down the runway at Roosevelt Field on Long Island.

When Warren heard the announcer say that Lindbergh planned to turn east over Long Island Sound, he rushed out of his house in the hopes of seeing him fly past. Looking up into the sky, Warren suddenly heard the sound of a distant plane engine. It was out over the water and he couldn’t see the plane, but for a minute or two he could hear the distinctive whine of the Wright Whirlwind engine, all the time imagining the young Lindbergh in the cockpit as he flew alone into the unknown.

From that moment on, he wanted to fly.

The worldwide economic depression altered his career plans, as it did for so many others. In the 1930s, there was no demand for pilots, but there was always a need for teachers, and as the war approached, he was finishing his education at Danbury Teachers College. While there, he fell in love with a fellow student, Elizabeth “Libby” Minck, and they became engaged. The vivacious Libby was committed to helping Warren “have more fun” in life.

Then the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. It came as a shock to Warren’s family when he went straight up to Hartford the following day and volunteered for the army air forces, just as Ted Wilken had done that same day in Manhattan.

They may have been different men, but in the course of training together, they learned they could count on one another. Warren never disappeared within himself while in the air. He was always focused on the tasks at hand, and ready to deal with the unforeseen problems that often cropped up in the heavy bombers. Unlike many copilots, he seemed born to the controls, and Ted felt comfortable turning the plane over to him.

At 0515, the two men watched an exploding flare shoot skyward near the control tower.