Authors: Kevin Cook

Tommy's Honor (30 page)

Photo 15

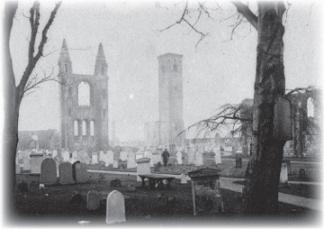

Tom in the Cathedral churchyard, on his way to Tommy’s memorial.

PILOGUE

St. Andrews Forever

T

he Open Championship has not been held at Prestwick since 1925. The Prestwick links doubled in size after the club bought land north of the old stone wall and extended the course from twelve to eighteen holes—the St. Andrews standard—but in time the tournament outgrew its birthplace. Today Prestwick is quiet, the breeze off the Firth of Clyde skimming shaggy dunes where the schoolboy Tommy Morris ran. Goosedubs swamp is long gone, drained and re-turfed. The links’ humps and hollows, blessedly free of whins in the Morrises’ day, are chockablock with whins planted later to make the course look more like a “classic” links, which is to say more like St. Andrews. The only sign that the Open began here at Prestwick is a cairn on the spot where the first teeing-ground used to be. A plaque on the cairn gives the length of Tom’s opening hole, 578 yards, and the date of the first Open, October 17, 1860. There is no mention of Tommy’s miracle three on this hole in the 1870 Open, or his 1869 ace at the Station Hole, golf’s first recorded hole-in-one, or his four consecutive Open victories on this course, but then it’s a small plaque.

St. Andrews is a different story. The town’s golf heritage is all over the place, from Tommy’s memorial in the Cathedral cemetery to the £90 hickory putters in the souvenir shop by the Home green to the £822-a-night Royal & Ancient Suite at the hulking Old Course Hotel to the golf-ball-shaped mints in the Tourist Centre on Market Street. This is Provost Playfair’s dream come true with a vengeance, the thousand-year-old town reborn as golf’s capital. Where generations of religious pilgrims once came looking for Saint Andrew’s kneecap, golfers now make pilgrimages to the Old Course. It was not the first course but it is the most important, due largely to the work Tom Morris began here in 1864, when he brought his family home from Prestwick.

Tom took over a mangy links that wound along narrow footpaths through stands of whins, with putting-greens pocked by heather, crushed shells, and bare dirt. He turned it into a course that was the envy of the world. As a player, he won four Opens and helped make the professional game respectable. Tom heard his supporters shout “St. Andrews forever” when he beat another town’s champion and heard the same glad shout when Tommy won the Championship Belt. When Tommy surpassed him he became his son’s ally and playing partner, and after Tommy died he carried on for decades as the game’s G.O.M., golf’s living memory and tireless publicist. No one ever did more for his sport and his native town.

The Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews has been the game’s ruling body since 1897, when Tom ceded his role as the ultimate authority on balls that landed in beards or went down rabbit holes. Today the R&A oversees golf everywhere except in the U.S. and Mexico, where its younger cousin the USGA rules. Today there are 50 million golfers worldwide, playing on more than 30,000 courses, each of which can trace its lineage back to the course that Tom remade with his callused, scarred hands.

Today he oversees the Old Course from a spot halfway up the west wall of the R&A clubhouse. A bronze bust there, inscribed

TOM MORRIS 1821 1908

, shows the most famous St. Andrean in a buttoned tweed jacket and full Mosaic beard, looking to his right, toward the first tee, as if to say, “You may go now, gentlemen.” Golf’s G.O.M. would be amazed to see golfers queuing up to pay £120 to attack his old links with titanium drivers and anvil-shaped, milled-aluminum putters. He might enjoy the golf-ball ads that show him as a ghost gaping at a three-piece, 392-dimple polybutadiene ball, and he would surely love another wonder: a £5 note with his picture on it, issued in 2004 by the Royal Bank of Scotland to mark the R&A’s 250th anniversary. In the twenty-first century, the symbol of the R&A is not a red-jacketed gentleman or even a full member of the club, but the son of John Morris the weaver.

The Open returns to the Old Course every five years. The tournament Tom helped create, now run solely by the R&A, is golf’s premier event. In all of sport, only the Olympics and soccer’s World Cup draw more television viewers worldwide. The winner is not merely the Champion Golfer of Scotland anymore; he is “Champion Golfer of the Year.” First-place money has grown from £0 in the Open’s first four years, when custody of the Belt was thought to be reward enough, to a year’s custody of the Claret Jug and £720,000.

The Open champion at St. Andrews in 2000 and again in 2005 was Tiger Woods, a former junior-golf celebrity who turned professional at age twenty and soon reached a level of dominance unseen since Tommy’s day. But Woods struggled after his 2005 Open title. He couldn’t hit his driver in the fairway. Then came news that Woods’ father, Earl, was dying of prostate cancer. Tiger pressed to win for his father, but only played worse. Earl Woods died two months before the 2006 Open Championship at Royal Liverpool Golf Club in Hoylake, England. This was the course that George Morris, Tom’s brother, laid out in 1869, digging the holes with a penknife, the course where Tommy won the Grand Professional Tournament of 1872. Hoylake is flat and hard with knee-high rough—no place for a crooked driver. During Open week in 2006, Woods left his driver in the bag and played four rounds that Old Tom would have applauded, hitting irons off the tees, tacking his way from point to point, bouncing approach shots onto the greens. He had a miracle shot of his own, a 205-yard 4-iron that bounded into the cup for an eagle deuce. Later he holed a final putt for a two-stroke win and then, unexpectedly, burst into tears. “I miss my dad so much,” said Woods. “I wish he could have seen this one last time.”

Tom Morris had the joy of seeing all four of his son’s Open victories and the sorrow of outliving all five of his children: Wee Tom, Lizzie, Jack, Jimmy, and Tommy, the one everybody wanted to talk about.

Tom collected testimonials to Tommy’s genius. There were many, but one will do here. In the early 1900s William Doleman, who had been low amateur in Tommy’s Opens, answered partisans of the Great Triumvirate—Harry Vardon, J.H. Taylor, and James Braid—who claimed old-timers like Doleman romanticized Young Tom Morris. “I know with whom lies the prejudice, and I leave all such to love their own darkness,” Doleman wrote. “Some of these moderns are grand golfers, no doubt, but the more I think out these things, the more I am convinced of Tommy’s surpassing greatness.”

Just inside the R&A clubhouse is a glass display case that holds the Claret Jug. The first name on the trophy is

TOM MORRIS JNR

, the latest is

TIGER WOODS

. Between them are Vardon, Taylor, Braid, Bobby Jones, Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, and sixty-seven others, all members of the game’s most exclusive fraternity. The Claret Jug may be the most important trophy in golf, but it is not alone in its display case. Above it hangs another prize: Tommy’s Championship Belt. In 1908 Tom’s grandchildren, following his wishes, gave the Belt to the R&A so that it could be seen by all who entered the clubhouse.

Moments after Tom went looking for the loo at the New Club on May 24, 1908, according to the

St. Andrews Citizen

, “the noise of someone falling was heard…. Old Tom was found in an unconscious condition.” It was mercifully quick: He cracked his skull at the bottom of the stairs and never woke up. But perhaps Tom had time for a last blink of thought. An eighty-six-year-old man falling in the dark, he might have seen the links in the late-day sun that casts shadows over every bump and makes the land look like water. He might have seen his son again, a brave boy knocking in a putt to beat his Da and then flinging his putter straight up. Whatever Tom believed his sins to be, he had lived the last thirty-three years of his life in Tommy’s honor.

O

ne perk of writing a book is that you follow leads that lead to friendships. Among the pleasures of working on

Tommy’s Honor

was meeting Dr. David Malcolm of St. Andrews, whose intellect may be matched only by his warmth and generosity. When “Doc” Malcolm turns his eye to golf history, legend and treacly sentiment give way to facts and figures. I was thrilled to discover that he shared my inclination to see Tom and Tommy Morris not as waxwork figures but as men who lived, breathed, joked, quarreled, loved, and died in a particular time and place. Doc welcomed me into his life and his work, providing details of Tom and Tommy’s lives as well as most of what I know about Margaret. He would not tell the story the same way I have (any mistakes are mine), but he has been unflagging in his support—a kind host, and a prized friend. I am also a fan of his wife, Ruth, a gifted artist who paints the world’s most gorgeous mackerels.

Dr. Bruce Durie of Strathclyde University in Glasgow wrote a clever 2003 novel called

The Murder of Young Tom Morris

—recommended reading for anyone who likes this book. Bruce shared his research with me: census entries, marriage and death records, and train schedules from 1864. He put me up in his home and whipped up the best haggis I have ever had. A word to the Grand Ole Opry: Dr. Durie is also a gifted country-western singer. Fond thanks to Bruce, with shout-outs to Adrienne and Jamie.

Golf fans know David Joy as the actor who plays Tom Morris in Titleist commercials with John Cleese. I’m glad to know David, whose one-man show as Old Tom is not to be missed (ditto for his book

The Scrapbook of Old Tom Morris

), as a source of historic books, photos, and artifacts. We used hickory clubs to knock balls around his garden, then talked for hours. When a question caught Joy’s fancy he would channel Old Tom, answering in a brogue that turned golf to “gowf” and made “Musselburgh” sound obscene. I still owe him a Tennent’s lager.

I owe thanks to many others in Scotland, England, and the U.S. Golf historian David Hamilton showed me around the R&A clubhouse and lent me a tie to wear inside. Peter Lewis, director of the British Golf Museum, shared his views on early professional golf and pointed me to the St. Andrews University Library (open till midnight!), where I spent many nights unspooling microfiche, poring over 135-year-old editions of the

St. Andrews Citizen

and the

Fifeshire Journal

. The staff there was patient and helpful, as were the folks at the Mitchell Library in Glasgow, where I thumbed the crinkly pages of original copies of

The Field

. At Royal Liverpool Golf Club in Hoylake, England, club historian Joe Pinnington played host to a round of golf at last year’s Open venue and gave me the key to Royal Liverpool’s library. At Prestwick Golf Club, Ian Bunch led me through his club’s archives. Robert Fowler and Neil Malcolm provided helpful facts from the archives of Royal North Devon Golf Club and Stirling Golf Club respectively. Director Rand Jerris and librarian Doug Stark welcomed me to the USGA Library in Far Hills, New Jersey, where the marvelous Patty Moran helped me chase nineteenth-century stories through the stacks and even gave me a lift to the Far Hills train station.

At Gotham Books, Bill Shinker supported my work from the start. A golf lover of the first flight, he is this book’s great friend as well as its publisher. In my book Bill is the top Gotham hero since Batman. Thanks also to a dynamic duo of editors, tireless Brett Valley and his predecessor, Brendan Cahill.

My agent, Scott Waxman, was crucial to

Tommy’s Honor

at every turn. We played alternate shot with the proposal, knocking it back and forth until it clearly laid out the course to come. I have come to rely on Scott’s judgment, his foresight, and his friendship, and am happy to be on his team along with the Waxman Agency’s Farley Chase and Melissa Sarver. Thanks also to Jim Gill of PFD in London for his work on the proposal.

Almost forty years ago my mother, Dr. Patricia Cook of Indianapolis, took me to Pleasant Run Golf Course for my first round of golf. Her kindness and love of the game are still part of my life. Thanks, Mom.

Much of the spirit of this father-son story had its source in the generous soul of Art “Lefty” Cook, minor-league pitcher, Hall of Fame father. Dad, I miss you every day.

On December 19, 1981, I went to a J. Geils Band concert with the best thinker and writer I know. In 1986 she took me to Scotland—my first pilgrimage—where the seeds of this book were sown. Pamela Marin, whose memoir,

Motherland

, is a model of deep feeling and crystalline writing, is my in-house editor, partner, and paramour. To her I owe the other great loves of our life—Cal, a jazz-playing big-game pitcher; and Lily, a young artist and horsewoman—whose spirits are as brave and beautiful as their mother’s.