Tomorrow We Die (3 page)

Authors: Shawn Grady

I didn’t tell the police about the notepaper.

I explained my presence as a simple welfare-check, doing a favor for the nurses on the fifth floor of Saint Mary’s. I recognized the cops, and they me, though not one of us knew the others’ names. But they made little of it. There wasn’t any trauma or sign of struggle on Simon’s body. They took down my personal info for their report and dismissed me with a “Have a nice night. See you on the streets,” and I set off with the blessing of their professional courtesy.

Sitting back in the driver’s seat of the Passat, I felt overcome with a sudden weighted exhaustion and wondered if I would be able to make the drive home. One look out of my window served as the catalyst for pressing onward. I longed for the comfort of the house I rented in old southwest Reno, where the world felt normal and beautiful. Where tree roots took precedence over sidewalks, and the mountains beyond stood as silent sentries. I shifted into gear, my thoughts free-floating with visions of sheltering oaks, mystical cottonwoods, and the peeling white bark of aspen trunks.

My phone vibrated. I fished it out. “Hello?”

“Jonathan?”

“Yeah?”

“It’s Joseph Kurtz.”

I should have recognized his voice. It was

Doctor

Joseph Kurtz, dean of the University of Nevada, Reno, Medical School. It was he who had first convinced me to pursue paramedic school – and more recently, med school. He’d coached me in my preparations for the MCATs.

With his ponytail and round spectacles, he’d always struck me as something of a misplaced beatnik. Decades ago he’d traded his beret for a stethoscope and in recent years had become the medical-school dean, bringing an out-of-the-box style of leadership that had garnered national recognition for the med school’s programs. He also happened to sit on the board that was considering my application for scholarship.

“Hey, Doc. Good to hear your voice.”

“You too, Jonathan. What’ve you been up to?”

“Oh, just happened to be checking up on a patient.”

“Right, right. That’s my good medic. Well, I won’t keep you, but I do have some very good news.”

My heart hopscotched.

“The board reviewed your MCAT scores, and they were very impressed. I am not sure if you’re aware of how few people in the country actually score in the ninety-eighth percentile. We examined your financial application, and I am happy to tell you that you’ve been approved for a full-ride scholarship.”

I held the phone out and looked at it in disbelief. Yep, Dr. Kurtz’s number. There was no way I could afford med school on the $11.70 an hour I was bringing home as a paramedic. My hopes had rested entirely on scholarship applications.

A full ride

. “I can’t believe it. Out of all the applicants?”

“You outshined them all, bud. Congratulations.”

“Wow. That . . . that makes my year.”

“Just thought I’d pass on the good news.”

“Thank you so much.”

“Hey, you earned it. Made my personal recommendation easy. But, look, the scholarship is provisional, based on an ongoing evaluation.”

“Like with grades?” I glanced out my side window and merged into a lane.

“That . . . and the board wants to make sure that its scholarship recipients are examples of the professional caliber that the med school produces.”

“How do they measure that?”

“It’s difficult to quantify. But for starters, I’d recommend that you enroll in the summer prep courses.”

“That’s all stuff I’ve pretty much taken.”

“I know. I know. But it shows the board that you’re serious and committed. This is a huge gift, and you don’t want to do anything to jeopardize it, right?”

Summer prep was a full-time commitment. I doubted that I could even keep up per diem hours on the ambulance. “What about meals and lodging? The scholarship program only covers that during the main school year.”

“We discussed that and have decided to make an exception for you.”

That only gave me a month. I’d have to give notice on my lease, move everything out, put some stuff in storage. And my dad –

“Jonathan?”

“Yeah? Sorry. Just taking it all in. I’m definitely on board.”

“That’s what I like to hear. Well done, bud.”

“Thanks again.”

After hanging up, I went on autopilot for the next couple of miles, blinking out of my reverie when I pulled onto my driveway. The glow I felt inside dampened a bit as I parked in the cave-like garage. The walls of my house had been built with stones that came out of the hole the original builder dug for the basement back in the thirties.

My

house only because it had come to feel that way after renting for the past four years. My dad lived there too. And I always had to qualify this – no, I didn’t live with my dad. Yes, I did live with him. He rented a room from me. In the house that I rented.

Street light stretched through open blinds, lending the only light inside. I sat in the dining room and stared out the back window. Closer than in winter, Orion ran up from the mountains into the night sky, Ursa Major still eluding him at an angle.

The day had kept me moving, doing, talking. As the high waned from the scholarship news, the inevitable quiet of evening crept in. It made it impossible to ignore the shadowy plane of hurt that lay just beneath the surface of my consciousness, ever present and waiting for me to slow down. The memory of that day . . . the long lingering wound that refused to mend.

Was I fooling myself? Was I foolish to think that med school and becoming an ER physician would make things any different, that it would somehow enable me to overcome the pain?

To outwit death?

The rain from that day didn’t stop, nor did the images of that shattered windshield.

I traced a finger over the small scar at my hairline.

My father ambled in wearing boxers and a collared button-up shirt. “Hey, Jonner.” He held an empty gin glass that he took to the kitchen.

He rarely drank in front of me. As though that would somehow cross a line. It would actually admit that he was doing it. That he was an alcoholic. And it would set a bad example for his son. Didn’t matter that I was twenty-six and doing more of the caring and providing for him than the other way around. Only God knew how he’d fare if I left him alone.

But I would leave him – in a month’s time. “Hey, Dad.”

Tap water echoed in his glass. “How was the day?” He said the words as if they were lyrics to a song. I knew by then that he wasn’t inquiring so much as delivering a requisite greeting, like saying the pledge of allegiance.

I counted the stars in Orion’s Belt. The moonlight iced blue the peaks of Mount Rose.

I took a deep breath. “I got the call today. I made it. A full-ride scholarship to UNR Med School.”

Red lights from an airplane diminished as it ascended from the valley. The bare limbs of our oak shook with a sudden breeze.

I turned. The kitchen was empty. The flickers of my father’s television illuminated the hallway.

The thin façade of normalcy fell away, and the dark ocean of pain churned inside of me.

I grimaced and pushed my lips together.

“Good night, Dad.”

I jolted awake with my alarm clock at 5:20 Saturday morning

.

I opened the blinds and stared at the sliver of dawn over the eastern hills. In the kitchen I flicked on my iPod at its docking station. Charlie Parker bebopped from the speakers as I brought the paper in from the front doorstep.

I used to be in the habit of reading a chapter from the Bible each morning. A “quiet time.” Silence, however, had become increasingly unpalatable, and subsequently, minutes that should have been spent conversing with God were now filled with distractions and noise, the modern panacea for a troubled soul.

I stared into the pantry. A box of Alpha-Bits remained the last cereal selection. Yeah, Alpha-Bits. Shopping when I was hungry was always a bad idea. I’d go to buy the staples and come home with Fruity Pebbles and beef jerky.

I sat with my bowl and glanced down the hallway. The door to my dad’s room hung ajar, his snoring rhythmic and hard to ignore. My head felt cloudy and unfocused. I was about to take a bite of cereal when a grouping of letters in the milk caught my attention.

REPA

I used my spoon to move the A to the front and guided an O to the end.

AREPO

“Arepo . . .”

“Arepo the Sower holds the wheels at work . . .”

I brought my hands away from the bowl, as though it had become a crystal ball. I took a glance at the ingredients on the side of the cereal box.

I need coffee.

After a quick shower, I changed into my medic uniform and threw a lunch into a collapsible cooler. I was out the door before six and arrived at the ambulance headquarters fifteen minutes before shift, meeting up with Bones in the ambulance bay.

Sitting in the back of Medic Two, he ran his fingers over medication vials bedded in foam inside a plastic drug container.

He looked up. “Greetings, visitor from planet Sleep. How goes your journey to the land of waking?”

I stowed my cooler in a front cabinet. “I think I want to return to my home planet.”

“Nonsense! You must check in with the system status authorities at once. Henceforth we will secure caffeinated beverages.”

He’d no doubt already had a couple cups. “It’s early, so let me translate. . . . Are you saying you want me to get the radios and drug keys?”

“Of course.”

I stepped out of the ambulance and walked down the hall that led to dispatch.

“That’s why you’re the best partner in the world, Jonathan. But don’t let that inflate your noggin.”

I started the engine and dropped the ambulance into gear.

Bones put us in service with dispatch. “Medic Two, McCoy and Trestle, oh-six-thirty to eighteen-thirty.”

“Copy,” dispatch said. “Post Rock Boulevard and Victorian Avenue.”

I looked over at Bones. “Starbucks?”

Bones, ever the connoisseur, said, “Never. No finer brew can be found than that which flows from the 7-Eleven.”

“How can you drink that stuff?”

“Nectar of the gods, Jonny-boy.”

“Try nectar of the broke.”

“And . . . that would be us.”

Morning poured into the valley, infusing color and warmth. Traffic grew heavier as the minutes passed. We parked at the post – a little hole-in-the-wall that Aprisa Ambulance leased with a couple couches and a TV. Bones strolled over to the convenience store. I unlocked the door, set my radio on the floor, and stretched out on a sofa. It smelled like dusty aged fabric. Bones walked in, laptop case strung over his shoulder, no plastic top for his coffee.

“Why don’t you ever get a top for those? Aren’t you afraid it’ll spill if we get a call?”

“That’s just it. If I get a top, then we’re sure to get a call.”

“That’s the goofiest logic I’ve ever heard.”

He lay down on the other couch and picked up the television remote. An episode of the seventies show

Emergency

emerged on the tube. “Hey, look,” he said. “There we are.”

“Roy and Johnny?”

“No. No. There. The guys with the white coats and the converted hearse.” He sipped his coffee. “Burt and Ernie with the gurney.”

I brought out Simon Letell’s notepaper and unfolded it. The markings still looked nonsensical. I set it on my stomach and looked up. “You ever heard of Arepo the Sower?”

“Does he live on Fourth Street?”

“No. Well, at least I don’t think so.” I straightened a corner of the paper. “You know our last patient from yesterday?”

“Yeah?”

“He AMA’d himself out of CCU.”

Bones turned on his side. “Really?”

“Yeah.”

He stared at my hands. “You healed him. You are a miracle worker.”

“He died outside his motel room last night.”

“Oh.” He sat back. “You should have given him a piece of your garment.”

“A piece of my garment?”

“ ‘Surely then he would not have died.’ ”

“Would you shut up?” I folded up the note. “Forget it. I shouldn’t have mentioned it.”

He sipped his coffee. Roy Desoto cranked up the black phone to talk to Rampart. The show went to commercial.

Bones glanced at me. “So, how’d you find all that out?”

“Oh, now you want to hear about it.”

“You have two minutes before

Emergency

comes back on.”

I held up the paper. “I went back to Saint Mary’s to return this.”

“What does it say?”

“Nothing intelligible.”

“Arepo the Sower? Is that what he said on scene?”

“Yeah.”

“Wasn’t there more to it?”

“ ‘Arepo the Sower holds the wheels at work.’ ”

Bones stared at the floor. “I can’t think of anything related. Have you Googled it?”

“The thought hadn’t occurred to me.”

“Let’s do it.” He sat up, unzipped his bag, and pulled out a silver and black Dell.

“Can you get Internet here?”

“I’ve got a mobile card.” He powered up the computer. Roy and Johnny returned. I muted it. The Google search field popped up on the laptop screen.

Bones typed in the Arepo phrase. “Yahtzee.”

“What?”

“Everyone says Bingo.”

“What do you see?”

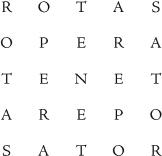

“Okay, one sec.” He clicked a link and scrolled downward. “It is a rough translation of the Latin words

sator, arepo, tenet, opera,

and

rotas

.”

“Latin?”

His eyes narrowed. “Check this out. They can be formed into a palindrome square.”

He turned the screen.

“Why would Simon say that to us?”

“He said it to you, not me.”

“Does it tell where the square comes from?”

He clicked to another page. His eyes tracked left to right. “Looks like there’s varying theories. The earliest finding is from a wall in Pompeii in 79 AD.” He scrolled down. “Wow. If you take each of the letters in the square and use them once, you form the Latin words ‘Our Father’ in the shape of a cross with two A’s and O’s left over.”

“Alpha and Omega?”

“I guess so.”

We studied the cross formation.

I shook my head. “That’s a trip.”

“It looks like there’s a lot of debate, but this page is suggesting that the inscription is early Christian. Like a pass code.”

“To avoid persecution. Secretly meeting in catacombs.”

Bones sat up and sighed. “Catacombs . . . catechism . . .”

I rubbed an eyebrow.

The radio beeped. Dispatch followed. “Medic Two, respond priority one for an unconscious subject, possible diabetic problem.”

I clicked the radio. “Medic Two copy.”

Bones packed up his laptop. A minute later we wailed down Prater Boulevard into an older section of the City of Sparks.

Bones drove aggressively but safe, for the most part. He only made me nearly soil my pants on one occasion – when he swerved late to get off the freeway and hit a curb going about fifty when the car beside us failed to yield.

“So left or right off Prater?” Bones said.

I glanced at the map book in my lap. “Left.”

We pulled up to the curb of a fifty-year-old single-story house. A plywood ramp had been constructed over the porch steps. We rolled the gurney to the front door, where an elderly woman holding a thick, avocado-colored cordless phone pointed with a trembling finger down the inner hall.

Bones unlatched the gurney seat belt that secured the airway bag and defibrillator. I did the same with the larger first-out bag.

A small black terrier appeared from behind a recliner, demonstrating its disapproval with snarling incisors. We made our way to the back room. A man in his eighties lay on the bed with foam at the corners of his mouth and slow, snoring respirations.

Bones rubbed the patient’s sternum with his knuckles. “Sir? Sir?”

No change. His skin was dusky.

“Jonathan, you got airway?”

“Sure thing.” I pulled a pinky-sized, trumpet-shaped green tube from the airway bag. I lubed it up and slid it in the patient’s nostril to make sure his tongue didn’t block air from getting into his lungs. “NPA’s in. You want me to bag him up a little?”

“Yeah, let’s get his color better.” Bones prepped the man’s arm for an IV.

I pulled out the bag mask to supplement his breathing. The fire department crew walked in, and the room grew smaller with the six of us, not counting the patient or his wife. Bones asked them to get a set of vitals and to assist ventilations. I handed the bag mask to a fireman.

Bones pulled the needle from the patient’s arm and handed it to me. I plunged a drop of blood from it onto the glucometer to check his blood sugar. The number 34 appeared on the digital display. Hence the reason he was unconscious.

I pulled the Dextrose 50% from the first-out bag and handed it to Bones. It was like clear syrup in a syringe.

He held up the medication cylinder and the needle attachment in separate fists. “Check it out – just like Roy and Johnny.” He popped the caps off with his thumbs and posed.

I shook my head. “I thought you said we were Burt and – ”

“One hundred over sixty.” A firefighter unstrapped the blood-pressure cuff.

Bones noted it on his glove.

He connected the dextrose syringe to the IV line and spoke as he pushed it in. “Okay, Jonathan, I want you to stand with the light at your back so your shadow casts over our patient here.”

I ignored him, as was often the best strategy, and gathered up plastic trash from the floor.

A bright light shone from behind me, throwing my silhouette over the patient’s legs.

The fire captain held his flashlight and winked. “How’s that, McCoy?”

Bones snickered. “Perfect. I have no doubt this man will be healed.”

The patient drew a sudden deep breath and lifted his head. His eyes darted around the room in confusion.