Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends (6 page)

Read Too Good to Be True: The Colossal Book of Urban Legends Online

Authors: Jan Harold Harold Brunvand

He inspected the walls and flower vases. He didn’t find a thing. But as he walked across the room, he noticed a lump beneath the carpet. He pulled it back and found a metal plate. Just to be sure, he took out the screws. They went to bed.

“Did you sleep well, new comrades?” the desk clerk asked as they were checking out the next morning.

“Just great,” they said.

“Is good to know this for commissar of hotel report,” the clerk said. “Peoples in room below yours had only bad things to say.”

“How’s that?”

“Chandelier fall on them at night.”

From Alex Thien’s column, “Wary Americans check hotel room,”

Milwaukee Sentinel,

March 19, 1990. The hotel clerk’s mangled English is typical of such travelers’ tales. The Cold War version of the above

glasnost-

era legend was told in Dick Beddoes’s

Pal Hal

(1989), p. 190, a book about Canadian hockey-team owner Harold Ballard. This time it’s told about hockey star Frank Mahovlich and his wife staying in a Moscow hotel during a 1972 series of games played against the Soviets. All very well, except that the

Little, Brown Book of Anecdotes

(1985), edited by Clifton Fadiman, attributes the incident to Canadian-born hockey player Phil Esposito “in the early 1970s.” Mahovlich and Esposito did play together on Canadian teams that competed in Russia. Probably earlier than any of these versions set in the Soviet Union is one in which the fearful couple are honeymooners who think their friends may have bugged their room as a wedding-night prank.

Most traditional dog

stories are of the overblown super-heroic genre, and excruciatingly sentimental, as well. It’s the “man’s best friend” pattern: Rin Tin Tin once again saves the day or Lassie rescues little Timmy for the umpteenth time. (At least Wishbone, the dog hero of PBS, has a sense of humor—

and

wears cute costumes—while he’s fighting alongside the Three Musketeers or playing the title role in

Robin Hood.

)

Here’s a typical tear-jerker dog legend from Wales. The story is inscribed thus on a stone erected at the supposed site of the incident near Mount Snowdon:

G

ELERT’S

G

RAVEIn the 13th Century, Llewelyn, Prince of North Wales, had a palace at Beddgelert. One day he went hunting without Gelert

“T

HE

F

AITHFUL

H

OUND

”who was unaccountably absent. On Llewelyn’s return, the truant stained and smeared with blood, joyfully sprang to meet his master. The prince alarmed hastened to find his son, and saw the infant’s cot empty, the bedclothes and floor covered with blood. The frantic father plunged his sword into the hound’s side thinking it had killed his heir. The dog’s dying yell was answered by a child’s cry. Llewelyn searched and discovered his boy unharmed. But near by lay the body of a mighty wolf which Gelert had slain. The prince filled with remorse is said never to have smiled again. He buried Gelert here. The spot is called

B

EDDGELERT

I wouldn’t want to argue with a proud Welshman about the truth of this touching tale, which has been often repeated in books and articles and is told to every tourist. But, unfortunately, there’s no proof that such an event ever happened, and prototypical stories about a variety of misunderstood helpful animals go back before the Middle Ages and were recorded first in the Middle East. One nineteenth-century English folklorist called Gelert “a mythical dog” and referred to the story as being “primeval [and] told with many variations.” Recently, a brave Welsh historian dubbed the Gelert story “moonshine, or more exactly, a clever adaptation of a well-known international folktale.”

The Llewelyn and Gelert legend was retold in the New World, where it evolved into “The Trapper and His Dog,” a Northwoods variation of the same plot, much reprinted. As late as 1989 the legend re-emerged in a court of law as what we might call “the Gelert defense.” In

The People of the State of Illinois v. Robert Gene Turner,

according to the case summary of Turner’s appeal of his murder conviction, the defense lawyer had, in the original trial,

told the jury about [the lawyer’s] great-great-grandparents who lived long ago in rural Iowa. During an especially cold winter, the husband became ill and the wife had to take him 20 miles to the nearest doctor. She left her baby at home, under the protection of their faithful dog. When she returned, the home was a shambles and the dog lay bloody and near death. Because she could not find the baby, she assumed the dog had killed it and in a fit of anger she shot the dog. Only then did she hear the baby cry, and when she found the baby, there lay nearby a dead wolf. Though it appeared to her that the dog killed the baby, it had in fact saved the baby from the wolf.

The prosecutor began his response by commenting, “This is not a place for stories and quite frankly I don’t believe the wolf story….” The defendant’s appeal was denied. (

North Eastern Reporter,

2d series, vol. 539, p. 1204, pointed out to me by lawyer K. L. Jones of Oak Park, Illinois.)

The Gelert story and its direct spinoffs are traditional “rural” legends. What we get of the story in

urban

legend form, after further transformations along the way, is “The Choking Doberman,” which emerged in the early 1980s as another true dog story that was too good to be true. The prince’s palace became an ordinary home, and the wolf was changed to a burglar. The impulsive slaying of the dog was replaced by a trip to the vet, and the dog doc makes an emergency telephone call to the cops. A prime example of how this “new” urban legend is told is the first legend of this chapter, which, by the way, is just as much a “jumping-to-conclusions” story as are those in Chapter 1.

In general, urban legend dogs are more often victims than heroes (likewise the UL cats, gerbils, birds, and even babies). The pooches get cooked, crushed, and sometimes fooled into jumping out of an upper-story window. They get blamed for barging in where they are not invited and scolded for causing messes that they never created. Even a pet dog’s lifeless body gets no respect in the world of urban legends.

Read on for all of these themes, and notice, please, that I saved one of the most disturbing dog tales for the next chapter, where poetic justice is the overall operative theme.

LOST DOG

Description:

3 legs

Blind in left eye

Missing right ear

Tail broken

Neutered…

Answers to name of “Lucky”

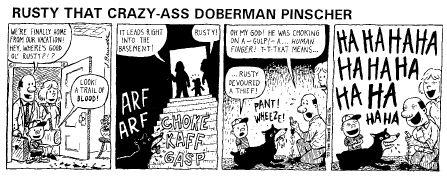

“The Choking Doberman”

E

lizabeth Bunn: Jordan and I were at dinner with friends of ours, Mike and his wife Shar…. His wife is a nurse, and she’s from the Upper Peninsula. OK, so we were out to dinner with them, and they live in Rosedale Park [a Detroit neighborhood]. And I’m not entirely sure how it came up in discussion. But they have dogs; they have two dogs, and she was pregnant at the time, and I think we were talking about dogs and security…and break-ins in Detroit, and they knew that we had dogs….[Discussion of her two dogs and their personalities]

And then Shar says, “Oh, God, you’re not going to believe this story,” that she heard from her sister who still lives in St. Paul, and her sister had told her of an incident that happened to a neighbor of her sister’s, an elderly woman who lived alone, I think was a widow. This woman had a Doberman Pinscher, in part for companionship and part for protection. And the woman came home one day, and the Doberman Pinscher was gagging [laughter]. Which anyone who has dogs knows is actually a common phenomenon. But whatever the dog was gagging on, it was stuck in his throat, and the woman got real concerned. So she took the dog to the vet, thinking the dog was going to choke to death.

So she got to the vet, and the vet said, “No problem, he’s just got something caught in his throat and we’ll get it out, but you might as well go home while we do it, because I don’t know how long it’s going to take.”

So the woman goes home, and as she’s entering her house the phone is ringing. And so she grabs the phone, and it’s the vet. And the vet says, “Don’t ask any questions, the police are on their way, just leave your house immediately.” So the woman has no idea what’s going on, but does as instructed and leaves the house. And the police do shortly arrive, and the police go immediately downstairs in the cellar, I guess where the dog was normally kept…they somehow knew to go right to the cellar where they found a guy [laughter] in shock, I mean frozen in shock with three fingers missing!

By Ivan Brunetti

[Janet Langlois:

Oh!

{laughs and groans}]

Bunn:…and the moral of the story, or the whatever of the story, was that the vet…that the Doberman Pinscher had eventually gagged up or thrown up three fingers. The vet had pieced together that it was a burglar and called the police and called the woman, and that was it.

Langlois: Amazing! Do you remember what your response was when you first heard it?

Bunn: Well, I totally believed it 100%, as did Jordan, and we were both just sick; it’s so disgusting, and yet so vivid! And I think part of it is…I grew up with dogs, and there’s very few dogs I’m really scared of, but Doberman Pinschers are…I’m just very very frightened of Doberman Pinschers. I’ve heard a lot of Doberman Pinscher stories….

[In retelling the story later] I do know that I chopped off a person in the telling. I did not say “a friend of mine’s sister’s neighbor.”…I said “a friend of mine’s neighbor when she lived in St. Paul.”…

Langlois: Can you locate the time when you first heard it?

Bunn: It would have been about April, May, or June of ’81.

As told by Elizabeth Bunn, a Detroit labor lawyer, interviewed in 1983 by Dr. Janet Langlois, Professor of English at Wayne State University. Extracts from Tape No. R1983(1), Wayne State University Folklore Archive, Detroit, Michigan. I wrote an analysis of this legend for my book,

The Choking Doberman,

and even worked out a genealogical chart of the legend’s development for

The Mexican Pet.

The most distinctive modern motif that has entered is the telephone call warning the victim of an intruder hiding in the house. The same plot device occurs in “The Baby-Sitter and the Man Upstairs,” included in Chapter 10. It’s also notable that a veterinarian saves the day, both in “The Choking Doberman” and in “The Mexican Pet” legend of Chapter 1.

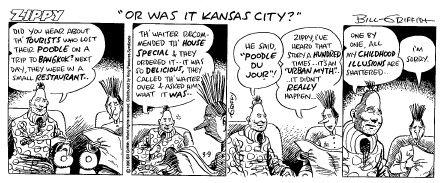

“The Swiss Charred Poodle”

W

hat Can You Believe?

Our recent series on Famous Fables & Legends of Our Time & Our Town drew such a thunderous lack of response that we have decided to accede to popular request and drop dead with yet another (will the last one to leave please turn off the presses?).

Actually, what inspired me to fly in the face of such unanimous opposition was the surfacing of the Chinese Poodle story on the front page of my very own beloved newspaper;

The Chronicle,

if memory serves. Like all deathless fables, the Chinese Poodle is on a 10-year cycle, so I guess it was due again. I printed it first in ’39, with a Chinatown setting. I heard it again in ’49, from New York, and in ’59 it “occurred” in Honolulu.

This time, a couple of years overdue [1971], it was circulated by the Reuters news agency from Zurich via Hong Kong, and goes:

“Hans and Erna W., who asked the Zurich newspaper

Blick

not to publish their full names, said they took Rosa to a restaurant and asked the waiter to give her something to eat. The waiter had trouble understanding the couple but eventually picked up the dog and carried her to the kitchen where they thought she would be fed.

“Eventually the waiter returned carrying a dish. When the couple removed the silver lid they found Rosa.”

Reprinted with special permission of King Features Syndicate

W

hen you first read that, you immediately smelled a rat, or at least a roast poodle, right? The tipoff is that Hans and Erna W. didn’t want their names published, the telltale sign of your true fable. People involved in these fabrications never want their names published.