Touchstone Anthology of Contemporary Creative Nonfiction (9 page)

Read Touchstone Anthology of Contemporary Creative Nonfiction Online

Authors: Lex Williford,Michael Martone

Where does pain worth measuring begin? With poison ivy? With a hang nail? With a stubbed toe? A sore throat? A needle prick? A razor cut?

When I complained of pain as a child, my father would ask, “What kind of pain?” Wearily, he would list for me some of the different kinds of pain, “Burning, stabbing, throbbing, prickling, dull, sharp, deep, shallow…”

Hospice nurses are trained to identify five types of pain: physical, emotional, spiritual, social, and financial.

The pain of feeling, the pain of caring, the pain of doubting, the pain of parting, the pain of paying.

Overlooking the pain of longing, the pain of desire, the pain of sore muscles, which I find pleasurable…

The pain of learning, and the pain of reading.

The pain of trying.

The pain of living.

A minor pain or a major pain?

There is a mathematical proof that zero equals one. Which, of course, it doesn’t.

The set of whole numbers is also known as “God’s numbers.”

The devil is in the fractions.

Although the distance between one and two is finite, it contains infinite fractions. This could also be said of the distance between my mind and my body. My one and my two. My whole and its parts.

The sensations of my own body may be the only subject on which I am qualified to claim expertise. Sad and terrible, then, how little I know. “How do you feel?” the doctor asks, and I cannot answer. Not accurately. “Does this hurt?” he asks. Again, I’m not sure. “Do you have more or less pain than the last time I saw you?” Hard to say. I begin to lie to protect my reputation. I try to act certain.

The physical therapist raises my arm above my head. “Any pain with this?” she asks. Does she mean any pain in addition to the pain I already feel, or does she mean any pain at all? She is annoyed by my question. “Does this cause you pain?” she asks curtly. No. She bends my neck forward. “Any pain with this?” No. “Any pain with this?” No. It feels like a lie every time.

On occasion, an extraordinary pain swells like a wave under the hands of the doctor, or the chiropractor, or the massage therapist, and floods my body. Sometimes I hear my throat make a sound. Sometimes I see spots. I consider this the pain of treatment, and I have come to find it deeply pleasurable. I long for it.

The International Association for the Study of Pain is very clear on this point — pain must be unpleasant. “Experiences which resemble pain but are not unpleasant,” reads their definition of pain, “should not be called pain.”

In the second circle of Dante’s

Inferno

, the adulterous lovers cling to each other, whirling eternally, caught in an endless wind. My next-door neighbor, who loves Chagall, does not think this sounds like Hell. I think it depends on the wind.

Wind, like pain, is difficult to capture. The poor windsock is always striving, and always falling short.

It took sailors more than two hundred years to develop a standardized numerical scale for the measure of wind. The result, the Beaufort scale, provides twelve categories for everything from “Calm” to “Hurricane.” The scale offers not just a number, but a term for the wind, a range of speed, and a brief description.

A force 2 wind on the Beaufort scale, for example, is a “Light Breeze” moving between four and seven miles per hour. On land, it is specified as “wind felt on face; leaves rustle; ordinary vanes moved by wind.”

Left alone in the exam room I stare at the pain scale, a simple number line complicated by only two phrases. Under zero: “no pain.” Under ten: “the worst pain imaginable.”

The worst pain imaginable…Stabbed in the eye with a spoon? Whipped with nettles? Buried under an avalanche of sharp rocks? Impaled with hundreds of nails? Dragged over gravel behind a fast truck? Skinned alive?

My father tells me that some things one might expect to be painful are not. I have read that starving to death, at a certain point, is not exactly painful. At times, it may even cause elation. Regardless, it is my sister’s worst fear. She would rather die any other way, she tells me.

I do not prefer one death over another. Perhaps this is because I am incapable of imagining the worst pain imaginable. Just as I am incapable of actually understanding calculus, although I could once perform the equations correctly.

Like the advanced math of my distant past, determining the intensity of my own pain is a blind calculation. On my first attempt, I assigned the value of ten to a theoretical experience — burning alive. Then I tried to determine what percentage of the pain of burning alive I was feeling.

I chose 30 percent — three. Which seemed, at the time, quite substantial.

Three. Mail remains unopened. Thoughts are rarely followed to their conclusions. Sitting still becomes unbearable after one hour. Nausea sets in. Grasping at the pain does not bring relief. Quiet desperation descends.

“Three is nothing,” my father tells me now. “Three is go home and take two aspirin.” It would be helpful, I tell him, if that could be noted on the scale.

The four vital signs used to determine the health of a patient are blood pressure, temperature, breath, and pulse. Recently, it has been suggested that pain be considered a fifth vital sign. But pain presents a unique problem in terms of measurement, and a unique cruelty in terms of suffering — it is entirely subjective.

Assigning a value to my own pain has never ceased to feel like a political act. I am citizen of a country that ranks our comfort above any other concern. People suffer, I know, so that I may eat bananas in February. And then there is history…. I struggle to consider my pain in proportion to the pain of a na-palmed Vietnamese girl whose skin is slowly melting off as she walks naked in the sun. This exercise itself is painful.

“You are not meant to be rating world suffering,” my friend in Honduras advises. “This scale applies only to you and your experience.”

At first, this thought is tremendously relieving. It unburdens me of factoring the continent of Africa into my calculations. But the reality that my nerves alone feel my pain is terrifying. I hate the knowledge that I am isolated in this skin — alone with my pain and my own fallibility.

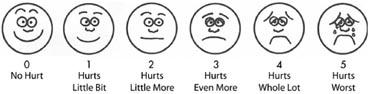

The Wong-Baker Faces scale was developed to help young children rate their pain.

The face I remember, always, was on the front page of a local newspaper in an Arizona gas station. The man’s face was horrifyingly distorted in an open-mouthed cry of raw pain. His house, the caption explained, had just been destroyed in a wildfire. But the man himself, the article revealed, had not been hurt.

Several studies have suggested that children using the Wong-Baker scale tend to conflate emotional pain and physical pain. A child who is not in physical pain but is very frightened of surgery, for example, might choose the crying face. One researcher observed that “hurting” and “feeling” seemed to be synonymous to some children. I myself am puzzled by the distinction. Both words are used to describe emotions as well as physical sensations, and pain is defined as a “sensory and emotional experience.” In an attempt to rate only the physical pain of children, a more emotionally “neutral” scale was developed.

A group of adult patients favored the Wong-Baker scale in a study comparing several different types of pain scales. The patients were asked to identify the easiest scale to use by rating all the scales on a scale from zero, “not easy,” to six, “easiest ever seen.” The patients were then asked to rate how well the scales represented pain on a scale from zero, “not good,” to six, “best ever seen.” The patients were not invited to rate the experience of rating.

I stare at a newspaper photo of an Israeli boy with a bloodstained cloth wrapped around his forehead. His face is impassive.

I stare at a newspaper photo of a prisoner standing delicately balanced with electrodes attached to his body, his head covered with a hood.

No face, no pain?

A crying baby, to me, always seems to be in the worst pain imaginable. But when my aunt became a nurse twenty years ago, it was not unusual for surgery to be done on infants Without any pain medication. Babies, it was believed, did not have the fully developed nervous systems necessary to feel pain. Medical evidence that infants experience pain in response to anything that would cause an adult pain has only recently emerged.