Traitor to His Class: The Privileged Life and Radical Presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (31 page)

Authors: H. W. Brands

Tags: #U.S.A., #Biography, #Political Science, #Politics, #American History, #History

In all of her new responsibilities she found a purpose she hadn’t known before. Her husband needed her, really needed her. Did he

love

her? That was a harder question. Did

she

love

him

? Equally difficult. But he needed her, and she liked the feeling. It was a beginning—or, more precisely, a new beginning.

L

OUIS

H

OWE’S RESPONSE

to Roosevelt’s illness was similar, in certain respects, to Eleanor’s. Howe hadn’t known quite what to do with himself as Roosevelt segued from public office to the private sector. Almost a decade earlier Howe had hitched his wagon to Roosevelt’s star, and then proceeded to promote that star in every way possible. He still intended that Roosevelt should be president someday, and he be Roosevelt’s chief adviser. But the 1920 election delayed the unfolding of Howe’s design, forcing Roosevelt into the private sector and Howe himself to find new work. The Navy Department let him remain through the transition to the Harding administration, then thanked him for his eight years’ service and sent him on his way. Roosevelt offered to bring him to Fidelity & Deposit, as his assistant. Howe accepted the offer with reservations, being unfamiliar with the bonding business and uncertain where his relationship with Roosevelt was headed.

Roosevelt’s illness changed everything. From the moment Howe heard the diagnosis of polio, he recognized his new calling, as the agent of Roosevelt’s recovery. Physical recovery would be welcome, of course, but Howe was most concerned with Roosevelt’s political recovery. A politician didn’t need to walk; he needed to think—and plan and coax and cajole and threaten. He didn’t need legs; he needed only a sound head. Perhaps, in retrospect, Howe now let himself imagine that Roosevelt’s very athleticism had served him poorly as a politician, making him appear a lightweight beside those men who devoted themselves entirely to the governing arts. Perhaps Howe perceived the polio as leveling the ground between himself and Roosevelt. Howe’s small stature and compromised health had always left him at a physical disadvantage to Roosevelt; Howe now stood taller than Roosevelt and enjoyed the edge in mobility. Moreover, Howe could command Roosevelt’s attention as never previously; henceforth when they sat down to plot out Roosevelt’s future, Howe could be sure the boss wouldn’t bounce away for a sail or a round of golf.

And at some level Howe must have appreciated that Roosevelt’s disability guaranteed his—Howe’s—indispensability. Roosevelt had first leaned heavily on Howe during his reelection campaign of 1912, when typhoid fever had prostrated him and he had no one else to turn to. Howe had proved his mettle sufficiently for Roosevelt to take him to Washington and the Navy Department. But as Roosevelt’s career advanced, he attracted other men prepared to devote themselves to his future, and by the time he joined the national ticket in 1920 he had his pick of political suitors. It certainly occurred to Howe that he might be jilted—if gently, as Roosevelt was a gentleman. The polio fairly precluded such a separation. The summer suitors would find other prospects; Roosevelt would have to rely on Howe, just as in 1912. Only this time the reliance would be long-term, perhaps permanent.

Howe never articulated this thinking, at least not in any form that survived. Perhaps he never laid it out completely in his own mind. He certainly didn’t explain to Eleanor or Franklin what he was up to. He simply made himself useful—finding and transporting doctors, keeping reporters and other nosy people at bay, reassuring Eleanor and Roosevelt himself. “Thank heavens,” Eleanor wrote of Howe amid the worst of Franklin’s physical crisis. “He has been the greatest help.”

S

ARA

R

OOSEVELT WAS

nearing the end of her annual European vacation when Franklin became ill. Eleanor didn’t inform her of her son’s condition. “I have decided to say nothing,” she told Rosy. “No letter can reach her now, and it would simply mean worry all the way home.” Eleanor sincerely wished to spare Sara helpless fretting, but she probably had an additional motive. Eleanor knew her mother-in-law well enough to realize that she would attempt to assume charge of Franklin’s recuperation. Eleanor wouldn’t be able to resist Sara’s influence entirely, if only from financial considerations. Franklin would be unable to work for some extended period, and already it was apparent that his medical care would be costly. Not long after William Keen left Campobello, the eminent doctor sent his bill “for $600!,” as Eleanor wrote in amazement. But Eleanor, who had been fighting Sara over Franklin ever since the young lovers first told her of their relationship, had no intention of surrendering her husband at this late date. Maybe she had learned it from Louis Howe, perhaps she intuited it on her own, but Eleanor understood that knowledge is the prerequisite to power, and she determined to maintain control of knowledge of Franklin’s condition as long as she could.

Of course Sara had to be informed eventually. Her ship was scheduled to arrive in New York at the end of August; a few days before it docked Eleanor wrote: “Dearest Mama,…Franklin has been quite ill and so can’t go down to meet you on Tuesday.” She offered nothing more in explanation and sent the note to Rosy, who greeted his stepmother’s boat in Franklin’s stead and delivered Eleanor’s message.

The very lack of details in Eleanor’s message must have tipped Sara to the seriousness of her son’s condition; her sensitivity on anything touching Franklin was exquisite. Whatever she guessed, Rosy and Fred Delano, who also met the boat, supplied the facts as soon as it docked. Sara naturally felt terribly for Franklin—for his present and future pain, for his loss of mobility, for the blow to self-esteem of one whose identity had been closely connected to his physicality. But much as for Eleanor and Louis Howe, the polio gave Sara cause to lay a new claim on Franklin. She had never shared her son gracefully—not with Eleanor, not with the world at large. Her fondest hope had been for him to ease into the role his father had vacated, as the seigneur of Springwood. He had chosen politics instead. Now Sara assumed that politics was out of the question—or at least she hoped it would be. Franklin would retire to Hyde Park; what else could he do? “He is a cripple,” one family friend wrote to another. “Will he ever be anything else?” Sara didn’t have to hear such sentiments to know how common they were; she felt them herself. Perhaps she congratulated herself on maintaining control of the family money. Since he couldn’t work, he would have no choice but to honor her wishes and come home.

T

HE OBJECT OF

the unspoken competition had little thought at first for the plans or feelings of Eleanor, Sara, and Howe. Dr. Lovett had been right; depression was a real threat. Franklin Roosevelt had experienced occasional disappointment, as at his snub by the Porcellians at Harvard, and sadness, upon the death of his father and the first Franklin Jr. But he had never been really unhappy, a fact that reflected both his innate temperament and his life circumstances. Roosevelt’s temperament tilted toward the sunny side of any street, and his circumstances had been such as to shield him from most of what other people typically became unhappy about. Life had been very good to Franklin Roosevelt, and he knew it.

But suddenly life wasn’t so good. As his fever diminished and his head cleared, and as he learned the cause of his symptoms, he came to realize that paraplegia would be his lot for some considerable time, perhaps forever. His days of effortless physical grace had been cut short by an unlikely twist of evil luck. For the children’s sake he tried to put up a brave front, but his anger, fear, and frustration sometimes burst through. He exploded without warning during one visit by Bennett, startling Eleanor and taking even the doctor aback. For days and weeks he wondered what to make of himself, wondered whether life was worth living, whether all he had worked toward was suddenly and forever beyond his reach. The doctor’s prescription simply made things worse. Almost never had Roosevelt felt himself the victim of inexorable fate; on those comparatively rare occasions when things went wrong in his life, his natural reaction was to fight back, to launch a counteroffensive. But Dr. Lovett, the polio expert, told him

not

to do anything. Aside from the warm baths, he must simply rest: no massage, no attempts to move about, nothing that fatigued him at all. A harsher sentence for an activist personality was difficult to imagine; no wonder he was frustrated and depressed.

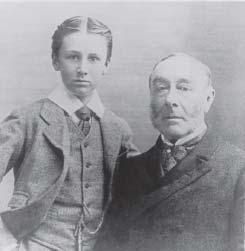

Photo Insert One

A

s Fauntleroy

A

t the helm on the Bay of Fundy