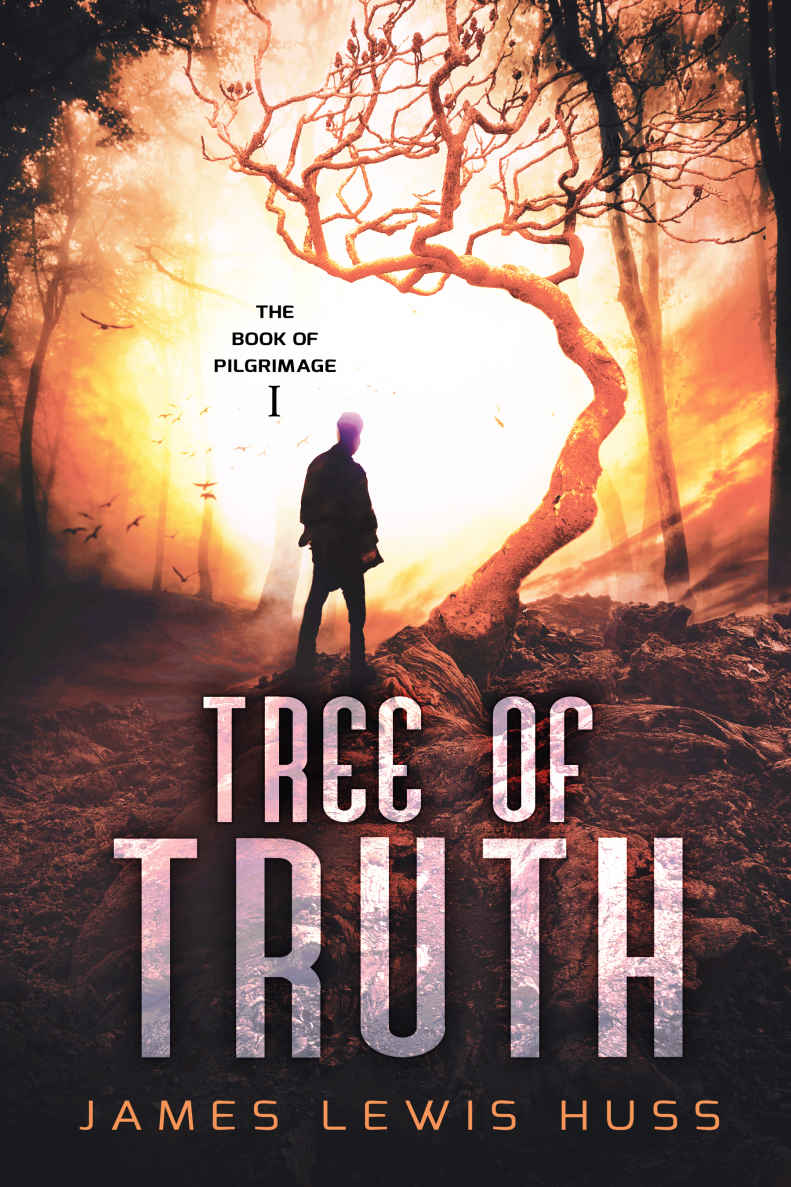

Tree of Truth (Book of Pilgrimage 1)

Read Tree of Truth (Book of Pilgrimage 1) Online

Authors: James Huss

Tree of Truth

©2016 James Huss

Elephantine Publishing, LLC.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written consent of the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are a product of the authors’ imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, either living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return it and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of the authors.

Cover design by Najla Chambers Designs

ISBN: 978-0-9968428-7-7

Tree of Truth

Book of Pilgrimage

, Book I

By James Lewis Huss

There's nothing that keeps its youth,

So far as I know, but a tree and truth.

–Oliver Wendell Holmes,

The Deacon's Masterpiece

(1858)

Chapter I

“My name is Benjonsen of the Appalachian Villages, Elder of the Pisgah Mountain Tribe, allied with the Eastern Commonwealth and Southern State, and loyal to the Union of New America. On the 12

th

August Moon, in the 81

st

Solar Revolution of the Third Century M.E., I departed on a quest for the Tree of Truth. This is my Book of Pilgrimage.”

*.*.*

“I woke up that morning with an unusual feeling of lightness. My wife slept as I crept onto the back porch to watch the sun rise. The morning was still and silent, except for the birds chirping hymns in harmonious discord to their celestial god as he emerged over the distant hills—to them, as to us, every day carries with it the known and the unknown, and to see those crimson rays crest the horizon once more shines relief on both man and beast.

“The mist had condensed in the valley below, forming a cloud like a blanket of newly fallen snow. The verdant mountainside boasted lush deciduous and evergreen trees, waiting patiently on winter’s chill to raze one and spare the other. The morning dew clung to its quickly evaporating life, twinkling its way into the atmosphere to join its cosmic twins.

“‘Happy birthday.’ Her voice betrayed a lingering sadness as the fractured melody mingled clumsily with the morning madrigals.

“I did not turn around, because I did not want her to see me crying. She went inside—I could hear her fumbling in the kitchen. I thought about the children and what they would do without me, but I knew Tiesse and our families would take good care of them. The birds had quieted when she returned with coffee. ‘Thank you.’ We were always polite to each other, especially in difficult times.

“She stood next to me, leaning carefully on the piecemeal railing and staring into the distance. ‘You’re going to find it,’ she told me with a gloss of flimsy optimism, her subtle fear exposing itself through each raspy crack in that delicate voice. ‘You’re going to find it, and you’re going to come home to me and the children, and we’re going to—’

“‘I’m not going to look for it.’ Her nervous chatter faded into hopelessness as I interrupted that desperate rambling. The silence stung. But we had talked about this. ‘It’s just a legend, a myth. Remember those books on science and medicine I showed you? Remember?’ She remembered. She had never believed in the first place. Besides, she had her own books, books about gods and goddesses, books about worlds within worlds, books about absurd realities—what were my books to her? She always believed in the unknown. When we were young it was endearing, but on that porch on that day I feared the unknown, and more I feared her faith in it.

“I stared at the umber grains hovering about the coffee in the bottom of my cup. It was good coffee, a birthday gift. Tiesse walked two days to get it—coffee beans never grew back home. The local beans were puny and insipid, so for the good stuff you’d have to barter with the cozening hill farmers to the northwest. (They always got the best of us foothills folk.) I turned the mug up, swilling the dregs and crunching the leftover grounds between my teeth. I felt its warmth, both from the coffee itself and the lengths to which my sweet wife went to get it. She pleaded with me, ‘Our fathers and our forefathers all sought the Tree. It is written in the ancient texts. It is the way of our people. You must seek it out—you could be the one.’

“I balked. ‘It

was

the way of our people. But who has found this magical Tree of Truth? Who lives to prove it even exists? Perhaps

the one

finds some other way.’ The sun was rising fast, and I only had a few hours with my family. I did not want to have that argument, so I left her on the porch. I should have told her I was going to find the Tree. I should have held her until I walked out the door. But I didn’t. I left her on the porch and went inside to say goodbye to my children.

“They were already up, and my precious little girl presented me a drawing as I opened her bedroom door. I sat with her and told her about the Pilgrimage. ‘I know, Daddy. The others say no one comes back, but I know

you

will. I believe in you, Daddy.’ My precocious Emily Dee—she could already read by the time she was three. To my chagrin, she found more joy in her mother’s books than mine. She believes I will find the Tree. She believes her daddy will return. But soon, maybe even now, the truth will have dawned upon her. It is not her I worry about.

“In the corner of his bedroom, my son Will was not very stealthily hiding in a hovel he constructed out of blankets and broomsticks. I could see the silhouette of his face turn as his eyes followed my movement across the room. I pretended not to notice, and then I pretended to leave. ‘Well I suppose I’ll have to see that rascally old boy o’ mine when I get back.’ I made a big deal of my salutations, pantomiming my goodbye in his direction. Before I reached the door he bolted, almost knocking me down. The little guy is strong for seven.

“He was crying. ‘I don’t want you to leave, Daddy.’ He was hardest to say goodbye to. I told him it was my path, and I would make him proud, and I told him to make me proud, so that one day when I returned we would both be proud of each other. He cried less after that. I let him sit in my lap until his mother bade me dress for the parade. I did as she asked—it was easier that way.

“Tiesse watched quietly as I donned my Shroud of Pilgrimage. It will follow me until I die, it will turn to ash on the pyre, and we will drift into the heavens together. It is the last garment my body will ever wear—my wife spent months sewing and stitching late at night, tearing the tender skin on her gentle fingers, straining to see by lantern the length of the sleeves to make sure they were not too long, nor too short. The fabric is strong and difficult to work, but she wanted it sturdy, for me. ‘Even if I wander ten years, this robe will be with me.’ I admired its rugged beauty, looking left and right at my arms akimbo. ‘The sleeves are perfect.’ Her forlorn expression eased its pain for a moment. ‘Ten years. Hah! That would be something!’ I should not have said that. It made her cry again.

“At noon the parade was made ready. I hugged and kissed my wife for what I hoped in some deserted corner of my mind was not the last time and stepped out onto the front porch. It was hot that day, and the air was thick with humidity, but my robe—I still don’t know where Tiesse got the fabric—was oddly breathable. It has been a good robe, and every day of my Pilgrimage I have needed it and used it and thought of her because of it. She knew I would. She was a good wife.

“The elders and youth lined the pathway that wanders from the village. I slowly ambled down the porch stairs, and before I reached the bottom brick, the pain that had delayed its attack for so long finally thrust its weighty spear into my chest—it felt almost impossible to walk off that porch, to leave my home, my children, my Tiesse. I ran up the stairs and hugged her and the kids once more, told them I loved them, and then took the hardest step I have ever taken, the last of my meager life and the first of my great journey. As I made my way out of town, the children offered gifts of food for the trip. I took as much as I could carry, and though my bags were full, they continued their oblations—it is tradition.

“Solemnity and celebration mingled uncomfortably that day. The elders wished me well. The children prophesied my return. The women held back tears, and the men showed me strength. Some spoke of the Tree of Truth with strained pretense, while others suffered the parade perfunctorily. The doubtful think the Pilgrims don’t notice. That day I thought I felt every emotion and every whim of every person there. I wasn’t offended by their lack of faith. Even I thought how foolish this rite, this ceremony of our primitive ancestors. No one ever returned from that trek of death. I never believed in the Pilgrimage or the Tree of Truth, but I set out on this journey anyway because it is our way. I, like many of us, repeated the rite for my family’s honor, for my wife’s comfort—it was not a choice.

“I looked back at the house once more. I wanted the last face I saw in that village to be my wife’s. I don’t know why—I’ve always seen her face in my mind as clear and beautiful as a summer day in the South, even now. Tiesse was still standing on the porch, still staring longingly in my direction. I stood there as the folk dispersed—they faithfully perform the rituals of the elders, but the toil chides their absence and beckons their return. I knew Tiesse would remain there motionless until I was out of sight, so I reluctantly turned again, this time never to turn back.”

Chapter II

“You’re crying.” I closed the Book and sidled over to Shelley, placing my arm around her shoulder gently. It was hard not to take her in my arms and hold her tight. But we were just friends—the best of friends, but still just friends.

“You know I always cry.” She wiped her eyes. “They’re all sad, but this one—this one especially. The way he talked about his wife and children—he must have loved them so much. How could they bear to let him go? Why did he have to go in the first place?”

“It’s the Pilgrimage.” It

was

sad in a way. But our world is full of sadness. “Nobody really wants to leave. But people expect it. They believe in it. Benjonsen didn’t have a choice but to leave.”

Where and why and how the Pilgrimage started, nobody knows. History was not recorded in the first years of the pestilence. People didn’t care about history, only survival. All the history we have after the Disease struck are Books of Pilgrimage, like Benjonsen’s Book, cryptic and personal records of the devastation, the recovery, the attempt to rebuild. Books of all sorts were important to us—they were our only means of understanding, of learning. All our teachers died young, and so our teachers were books, even Benjonsen’s.

I took the leather-bound Book and returned it carefully to the waxed leather pouch whence it came. I placed the package gently on the ground beside me and turned my attention back to Shelley. I hesitantly leaned in to hug her, and she responded with generous affection. It lit my face like the dawning sun, and hot blood rushed to my cheeks.

Several meters in the distance, a shrouded corpse rested against a gnarled and ancient tree standing alone in a field of white and purple foxglove. Behind him, the hills rolled gently from east to west, some pristine from grass and tree, and some with scarred faces from ancient glaciers. The modest mountains grew gradually into the sky, smoothed by millennia of ice, water, and wind. Our village sat in the shadow of those hills, in a humble valley carved out by a winding mountain river.

The Pilgrim’s body sat comfortably beneath the tree’s jagged, hoary limbs as though its spirit left without struggle, without hesitation, without surprise. A few flies meandered about the face and hands, but there was no sign of decay. It was a callow corpse, fresh from its death. The skin had yet slacked, the body had no bloat—from more than a few steps away it appeared as though the meditating Pilgrim might arise at any moment and carry on his way. But this one’s journey had ended, and all that was left of him now was a cloaked contre-jour of what once was a hard-working citizen, a loving father, a faithful husband. His Book of Pilgrimage alone would remain after the funeral flames delivered him from this earth.

“We have to send for them.” I helped Shelley to her feet and walked her over to the body by the tree. She stared at it nervously.

“What will they say?” I could hear anxiety in her voice.

“What

can

they say? We have only gone for a walk on a beautiful summer’s day. Besides, it’s our tradition. We found the Pilgrim—we have to make sure he has a proper funeral. We have to speak for him. We have to carry his Book of Pilgrimage to the Library and place it on the hallowed shelf.”

“Can’t you just—can’t you just do it yourself and pretend I wasn’t here?” She swept her raven tresses behind her ears and glanced upward into my eyes. I looked away and fought the irresistible urge to stare back at her. “Please.” She took my hand in hers. My heart trembled, not for the discovery of our secret adventure, but for her love.

“Is it wrong that we were together today? Are you ashamed?” I looked at her, but not directly into her eyes. I searched her face, dying to know, yet afraid to find out.

“No, Marlowe. It’s not that. But they’ll talk. And you know your family, your brother. You will be sixteen soon. He will expect you to marry. And you don’t even have a girlfriend.”

“Yet.” A childlike smile crept beyond control across my face. She let go of my hand and took a few steps away. The impish grin turned crestfallen frown. I closed the gap between us and put my hand on her shoulder. “I didn’t mean—”

“It’s not that. I—” She hesitated. “I like you, Marlowe.” She cast a terse glance into my wanting eyes, then coyly looked away again, as though she were searching for thoughts lost over the distant horizon. “But your family—surely they have already chosen a wife for you.”

“My brother is the leader of the family, but he will not tell me who to marry.”

She loosed a cynical laugh. “Your brother is a village elder. He practically runs this village. He

will

tell you who to marry. And you will marry her.” I snatched my clammy hand from her shoulder. But she was right. We married young. We had no choice. Men had to be fathers before they became Pilgrims, and women had to be mothers before they died. It was the only way to survive. We did not have the luxury of marrying for love like those in the ancient times.

I clutched Shelley’s arm gently. “We have to send for them.

Both

of us.” She could sense the wound she had inflicted and capitulated.

“Okay. We will send for them. Together.” She took my hand and held it tightly. We stood captivated by the departed, admiring the misery and the beauty of the breathless wanderer who lay before us, donned in the Shroud that left the comfort of family and friend on the back of that Pilgrim, followed him throughout his brief but treacherous journey, and would serve him once more as the sacred flame consumed them both upon the funeral pyre. The late traveler was a majestic being—upright, calm, accepting. Wandering in death’s shade without fear, he sat under these branches and dedicated his final hours to those who would remain, those whose lives might be spared from the Great Disease by some accidental clue buried within one passage, one phrase, one word of his Book of Pilgrimage, not knowing whether his path would lead to anything or nothing, for nothing had been discovered on any of these feckless journeys. But we embarked upon them anyway.

I looked closely at his face. It was a strong, youthful countenance—somewhat narrow, but defined along the jaws and in the cheeks. He stared at the ground before him through a slight gap in his sleepy eyelids. In that soft skin, still fresh from death, was a burgeoning masculinity in want of but a few more years of suffering under that life-giving star. There was no gaping mouth, nor horror of any sort in his expression. This face of death was not like the faces we read about in the stories of the ancient plagues—bulging eyes, jaws agape, absolute horror in the aspect. No, this Pilgrim died calmly, perhaps even happily, and the corners of his mouth seemed to reach ever so slightly for the heavens, yearning for the soul that would never return. He was smiling when the darkness came. The setting sun shone red upon his cheeks, and for a moment before the shadows of night chased that light away, there was life in the Pilgrim’s face. I reached out and gently closed his eyes.

*.*.*

Shelley and I crested the hill outside the village as the sun sank behind the opposite ridge, bestowing its orange glow upon the clear, late-summer sky. Two boys, Poe and Sam, themselves barely even sixteen years old, manned a makeshift guardhouse where the main street met the edge of town. In its former life it was an old storage shed, but dragged from the backyard of an Ancient’s well-equipped house and planted like a sentinel, it became a warning to those wandering and looting tribes that these houses and these buildings were not abandoned remnants of a time past—ours was a community, a village of people, and although not a fierce people, a people who would have to be confronted nonetheless. There was nothing so valuable in these country hamlets that those untamed and untaught vagabonds would fight for. They preyed on the weak, and to them, a community such as this was anything but weak. The people did not fear for their safety in and around their homes, but to venture beyond was a hazard indeed.

“Marlowe.” Poe emerged from the guardhouse with Sam directly behind, poking and prodding and giggling all the way. Turning sharply, Poe said, “Stop it, you germ!” Sam mocked the insult as he slunk back to the guardhouse. “What are

you

two

doing?” asked Poe. His tone was playfully suspicious.

“Nothing, Poe. Just taking a walk,” I said. Poe looked at Shelley, who looked away. After a few uncomfortable moments of silence, I blurted out, “Hey—guess what we found.”

“Marlowe!” Shelley chided my levity. “Show some respect.”

“What? It’s exciting.” She glared at me, and I relented. “Okay, okay.”

“A Pilgrim,” Poe said with arms folded, a look of smug self-satisfaction hanging upon his chin.

“A Pilgrim! We found him propped up against that gnarly tree in the meadow. You know, the one in the field just past the old stone church with the creepy graveyard? It’s not even a mile from here. Just over that hill.” I pointed to a hill in the distance. Poe squinted his eyes to see, stared for a moment, and then turned back to the guardhouse.

“Sam!” Poe called to the guardhouse. “Run fetch Elder Whitman.” Sam bolted at the sound of

Elder Whitman

. Elder Whitman had one job—funerals. It was his family tradition since the ancient times, but now it was more ritual than science, not like the old days. The Ancients used to prepare the bodies very carefully, with chemicals and surgery and even makeup. They buried their dead in the ground, and dotting the landscape to this day are carved stones that mark their burial plots. The wealthy ones were especially proud of themselves in passing—they sometimes left grand statues and great steles. Whitman was more a master of ceremonies, presiding over the bearing of the body, the benediction for the departed, the lighting of the pyre. He took his job very seriously.

Elder Whitman arrived with a horse, a cart, and a team of men. There were only a few horses in the village, mostly owned by the farmers and merchants. Horses were not easy to come by. The Ancients didn’t have much need for them. They had machines for everything. When the Great Disease came, there was chaos, destruction, and famine. In their starvation, the people ate those noble creatures almost to extinction, and when gas ran out and the people needed them again, they had become scarce and elusive. But in our little village, we still had a few.

“So,” Whitman said softly, “where’s this Pilgrim of yours?”