Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) (126 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

as a general expression, and that it could not be properly explained without a map. But I begged my colleagues to persevere. What would happen if the Foreign Secretaries met in September and discussed Poland and again reached a deadlock just when the winter was upon us?

Berlin, for instance, used to get some of its fuel from Silesia.

“No, from Saxony,” said Stalin.

Triumph and Tragedy

782

“About forty per cent of its hard coal came from Silesia,” I answered.

At this point Mr. Truman read us the crucial passage of the Yalta declaration, namely:

The three heads of Governments consider that the

eastern frontier of Poland should follow the Curzon

Line, with digressions from it in some regions of five to

eight kilometres in favour of Poland. They recognise

that Poland must receive substantial accessions of

territory in the north and west. They feel that the

opinion of the new Polish Provisional Government of

National Unity should be sought in due course on the

extent of these accessions, and that the final

delimitation of the western frontier of Poland should

thereafter await the Peace Conference.

This, he said, was what President Roosevelt, Stalin, and I had decided, and he himself was in complete accord with it.

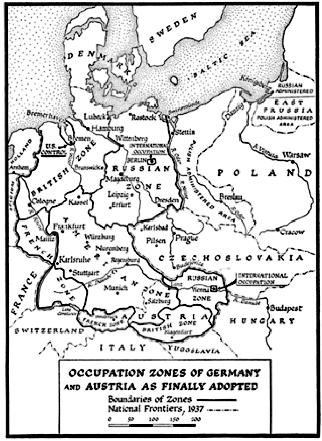

Five countries were now occupying Germany instead of four. It would have been easy enough to have agreed upon a zone for Poland, but he did not like the way the Poles had occupied this area without consulting the “Big Three.” He understood Stalin’s difficulties, and he understood mine. It was the way in which it had been done that mattered.

“Very well,” said Stalin. “We bound ourselves at Yalta to consult the Polish Government. This has been done. We can either approve their proposals or summon them to the Conference to hear what they have to say. We ought to settle the matter here, but as we cannot agree then it had better go to the Council of Foreign Ministers.”

At Teheran, he said, Roosevelt and I had wanted the frontier to run along the river Oder to where the Eastern Neisse joined it, while he had insisted on the line of the Western Neisse. Moreover, Mr. Roosevelt and I had

Triumph and Tragedy

783

planned to leave Stettin and Breslau on the German side of the frontier. Were we to settle the question or put it off?

“If the President,” he added, “thinks anyone is to blame, it is not so much the Poles as the Russians and the circumstances.”

“I understand your point, and that is exactly what I meant,”

answered Mr. Truman.

Meanwhile I had pondered over these questions, and I now said that we should invite the Poles to come to the Conference at once. Stalin and the President agreed, and we resolved to send them an invitation.

Accordingly, at a quarter-past three on the afternoon of July 24 the representatives of the Polish Provisional Government, headed by their Prime Minister, Bierut, came to my house in the Ringstrasse. Mr. Eden, Sir Archibald Clark Kerr, our Ambassador in Moscow, and Field-Marshal Alexander were with me.

I began by reminding them that Great Britain had entered the war because Poland had been invaded, and we had always taken the greatest interest in her, but the frontiers which she had now been offered and apparently wished to take meant that Germany would lose one quarter of the arable land she possessed in 1937. Eight or nine million persons would have to be moved, and such great shiftings of population not only shocked the Western democracies, but also imperilled the British zone in Germany itself, where we had to support the people who had sought refuge there.

The result would be that the Poles and the Russians had the food and the fuel, while we had the mouths and the hearths. We would oppose such a division, and were Triumph and Tragedy

784

convinced that it was just as dangerous for the Poles to press too far to the west as they had once pressed too far to the east.

I told them that there were other matters which troubled us.

If British opinion were to be reassured about Poland the elections should be genuinely free and unfettered, and all the main democratic parties should have full opportunity to participate and proclaim their programmes. What was the definition of democratic parties? I did not believe that only Communists were democrats. It was easy to call everyone who was not a Communist a Fascist beast; but between these two extremes there lay great and powerful forces which were neither one nor the other, and had no intention of being one or the other. Poland should admit as many as possible of these moderate elements into her political life instead of branding everyone who did not fit the preconceived definitions of the extremists.

In the present distracted state of Europe anyone with power could strike at his opponents and condemn them, but the only result was to exclude the moderate elements from political life. It took all sorts to make a nation. Could Poland afford to divide herself? She should seek as broad a unity as possible and join hands with the West as well as with her Russian friends. For example, the Christian Democratic Party and all those of the National Democratic Party who had not actively collaborated with the enemy should take part in the elections. We should also expect full freedom for the Press, and for our Embassy, to see and report what was happening before and during the poll. Only by tolerance, and even on occasion mutual forgiveness, could Poland preserve the regard and support of the Western democracies, and especially of Great Britain, who had something to give and also something to withhold.

Triumph and Tragedy

785

Bierut protested that it would be a terrible mistake if Great Britain, having entered the war for Poland’s sake, now showed no understanding of her claims. They were modest and took account of the need of peace in Europe. Poland asked for no more than she had lost. Only a million and a half Germans would have to be shifted (including those in East Prussia). These were all that remained. New land was needed to settle four million Poles from east of the Curzon Line, and about three million who would return from abroad, but even then Poland would have less territory than before the war. She had lost rich agricultural land round Vilna, valuable forests (she had always been poor in timber), and the oilfields of Galicia. Before the war about eight hundred thousand Polish farmhands used to go to Eastern Germany as seasonal workers. Most of the inhabitants of the areas the Poles claimed, especially Silesia, were really Poles, though attempts had been made to Germanise them.

These territories were historically Polish, and East Prussia still had a large Polish population in the Masurians.

Triumph and Tragedy

786

I reminded Bierut that there was no dispute about giving Poland the portions of East Prussia which were south and west of Königsberg, but he persisted that Germany, who

Triumph and Tragedy

787

had lost the war, would lose only 18 per cent of her territory, while Poland would still lose 20 per cent. Before the war Poland’s population was so dense (about eighty-three per square kilometre) that many Poles had had to emigrate.

The Poles only asked for their claims to be closely examined. The boundary they proposed was the shortest possible line between Poland and Germany. It would give Poland just compensation for her losses and for her contribution to Allied victory, and she believed that the British would wish her wrongs to be righted.

I reminded him that till now it had been impossible for us to find out for ourselves what was going on in Poland, since it was a closed area. Could we not send people into Poland with full freedom to move about and tell us what was happening? I favoured ample compensation for his country, but I warned him they were wrong to ask for so much.

Mr. Eden saw the Poles again at his house late that night.

Many subjects were touched upon. At ten o’clock next morning I had a stern talk with Bierut alone.

War, he said, provided an opportunity for “new social developments.” I asked whether this meant that Poland was to plunge into Communism, to which I was opposed, though of course it was purely a matter for the Poles. Bierut assured me that according to his ideas Poland would be far from Communist. She wanted to be friendly with the Soviet Union and learn from her, but she had her own traditions and did not wish to copy the Soviet system, and if anyone tried to impose it by force the Poles would probably resist. I said that internal questions were their own affair, but would affect relations between our two countries. Of course there was room for reform, especially on the great landed estates.

Triumph and Tragedy

788

“Poland will develop on the principles of Western democracy,” he answered. She was not small; she was in the centre of Europe; she would have twenty-six million Polish inhabitants. The Great Powers could not be indifferent about her development, and if this was to be on democratic lines, particularly on the English model, some changes would be inevitable.

I once more impressed on him the importance of free elections. It was no good if only one side could put up candidates. There must be free speech, so that everyone could argue matters out and everyone could vote, as was the case in Great Britain. I hoped that Poland would follow the British example and be proud of it. I would do all in my power to persuade Poles abroad to return to Poland at the right time. But his Provisional Government must encourage them. They must be able to start life again on honourable terms with their fellow-countrymen. I was certainly not satisfied with the behaviour of some Polish officers in suggesting that all Poles who returned would be sent to Siberia, though it was true that many Poles had been deported in the past.

Bierut assured me that none were being deported now.

I continued that Poland must have courts of law independent of the Executive. The latest development in the Balkans had been not towards Sovietisation but to police government. The political police arrested people on the orders of the Government. The Western democracies deplored it. Would Poland improve? Was the N.K.V.D.

leaving the country?

Bierut replied that, generally speaking, the whole Russian Army was leaving. The N.K.V.D. played no rôle in Poland.

The Polish Security Police were independent of them and Triumph and Tragedy

789

under the Polish Government. The Soviet Union could no longer be accused of attempting to impose such “forms of assistance” upon Poland. Conditions were returning to normal now that the war was over. He professed to agree with me about elections and democracy, and assured me that Poland would be one of the most democratic countries in Europe. The Poles did not favour police regimes, though exceptional measures had had to be taken to heal the serious rifts of war. About 99 per cent of the population were Catholics. There was no intention to oppress them, and the clergy, generally speaking, were satisfied.

I replied that Great Britain wanted nothing for herself in Poland, but only to see Poland strong, happy, prosperous, and free. There had been no progress after Yalta, but matters had improved greatly in the last few weeks. There was now a recognised Polish Government. I hoped that it would make itself as broad as possible, or at least make sure that the elections were as broad as possible. Not everyone had been equal to the terrible events of the German occupation. The strong resisted, but many average folk bowed their heads. Not all men could be martyrs or heroes. It would be wise to bring all back into the main stream of political life.