Truman (30 page)

Authors: David McCullough

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Political, #Historical

As much as he enjoyed going out to the farm to see his mother and sister, he had no desire ever again to live in the country. He loved the town. “He liked his walk up to the courthouse square,” said Margaret. “He liked people…he genuinely liked people and he liked to talk to them….”

In many ways it was still the town he had grown up in. Farmers crowded the Square on Saturday nights, but the rest of the week, nights were quiet, broken only by the sound of passing trains and the striking of the courthouse clock. Margaret Phelps and Tillie Brown still taught history and English at the high school. The town directory listed most of the old names of the original settlers—Boggs, Dailey, Adair, McClelland, Chiles, Hickman, Holmes, Ford, Davenport, McPherson, Mann, Peacock, Shank, not to say Truman, Wallace, and Noland. Harry knew nearly all the family histories—it was good politics to know, of course, but he also loved the town.

His devotion to Bess appears to have been total, no less than ever. On his travels, at summer Army camp, he wrote to her nearly every day. How had he ever gotten along without her before they were married was a mystery he pondered in a letter from Fort Riley, Kansas, the summer of 1930. “Just think of all those

wasted

years….”

“Have you practiced your music?” he wrote to Margaret from. Camp Ripley, Minnesota, another summer. He had splurged and for Christmas bought her a baby grand piano, a Steinway, a surprise she did not appreciate. She had dreamed of an electric train. “I’m hoping you can play all those exercises without hesitation. If you can I’ll teach you to read bass notes when I get back.”

As early as 1931 there was talk of Harry Truman for governor, a prospect that delighted him. “You may yet be the first lady of Missouri,” he told Bess. Whatever inner turmoil he suffered, however many mornings of dark despair he knew, the truth was he loved politics. He was as proud of the roads he had built and of the new Kansas City Courthouse as of anything he had ever accomplished, or hoped to. Work was progressing on the new Independence Courthouse, his courthouse, as he saw it, and everyone approved. “From the time of the establishment of Jackson County until now,” wrote Colonel Southern in the

Examiner

, “men with the same indomitable courage of the county’s namesake, Andrew Jackson, have dwelt in this ‘garden spot of Missouri’—with eyes always fixed on the future greatness of this great domain and with the thought uppermost to build, build, build a county that the rest of the state would be proud of.”

But the greater satisfaction for Harry was in what he had been able to do for ordinary people, without fanfare or much to show for it in the record books—things he could only have done as a politician. Years afterward, over lunch in New York with the journalist Eric Sevareid, he would describe how as a county judge in Missouri he had discovered that through a loophole in the law, hundreds of old men and women were being committed to mental institutions by relatives who could not, or would not, cope with their care or financial support, and how by investigating the situation he had restored these people to their rights and freedom. This, he said, had given him more satisfaction than anything.

“He loved politics,” remembered Ted Marks, “and he strived for something and never let loose until he got there. I think no matter what job he held he put all he had into it. He enjoyed it and did the best he knew how….”

He had not found his real work until late in life, not until he was nearly forty. But then, observed Ethel Noland, hadn’t he been a late bloomer all along? “He didn’t marry until he was thirty-five…. He didn’t do anything early.” Politics came naturally. “There,” she said, “he struck his gait.”

Harriet Louisa Gregg Young and Solomon Young.

Mary Jane Holmes Truman and Anderson Shipp Truman.

Martha Ellen Young Truman and John Anderson Truman at the time of their marriage, December 1881.

Harry S. Truman at about age ten.

In a graduation portrait of the Class of 1901, seventeen-year-old Harry Truman stands fourth from the left at the back. Bess Wallace is on the far right, second row, and Charlie Ross sits on the far left in the front row. The Latin inscription over the door says: “Youth the Hope of the World.”

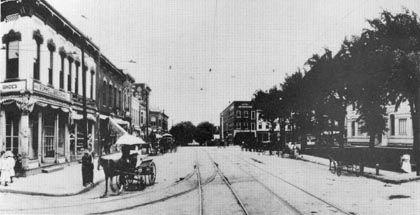

The center of Independence, Jackson Square, at the turn of the century. The courthouse is on the right.

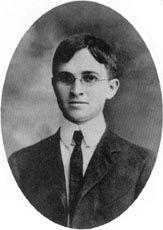

Truman at about the time he was employed as a clerk at the National Bank of Commerce, Kansas City. “His appearance is good and his habits and character are of the best,” wrote a supervisor.

Cousins Nellie and Ethel Noland, to whom he was the adored “Horatio.”

The junior partner of J. A. Truman & Son, Farmers, stands with his mother and grandmother Young by the front porch of the house at Grandview.

The work day began with his father’s call from the foot of the stairs at 5:30

A.M.

Here, Truman rides the cultivator across a field of young corn.

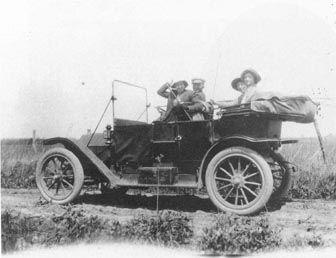

Truman at the wheel of the second-hand, right-hand drive, 1911 Stafford touring car that transformed his life. With him are Bess Wallace (in front), sister Mary Jane Truman, and cousin Nellie Noland.