Tumbledown (25 page)

Authors: Robert Boswell

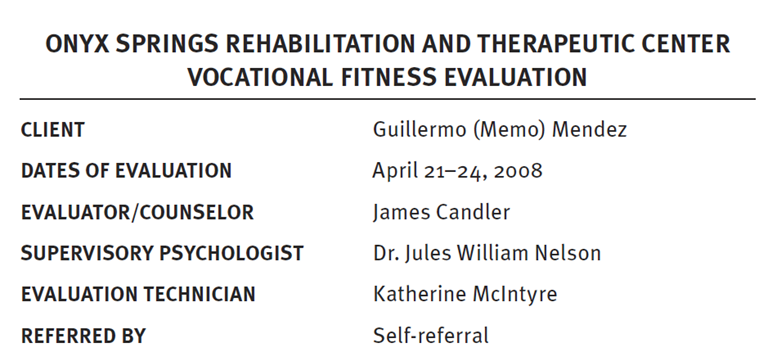

TYPE OF EVALUATION

A three-day evaluation of abilities, needs, talents, and shortcomings. (See full description of the three-day evaluation in

Addendum A.

) Assessments that require a psychologist’s input and interpretation were administered by the evaluator under the tacit supervision of the supervisory psychologist. (See

Addendum A

for details of counselor-administered psychological assessment.)

REASON FOR REFERRAL

Client articulates as follows: “I want to see what’s possible that I could do at some point down the road, and the sh_t that no way can I do, now or ever.” In concert with the evaluator, the reason for the referral was refined as an examination of vocational and educational aptitude, as well as a measure of emotional and psychological predilections and readiness.

CLIENT BACKGROUND

Guillermo Mendez is a twenty-one-year-old male of Hispanic ethnicity. Both parents are living and are second-generation immigrants from Mexico. His father is employed as a foreign-car mechanic by Griffin’s Auto Repair Services in San Diego; his mother is employed as a cashier at Big O Tires in Imperial Beach. Client reports that his family life as a child was loving and busy. He has four younger siblings, all of whom live with the parents in National City, California.

Client has a high school education (Sweetwater High School, National City) and is currently employed by the United States Army, holding the rank of private first class. His grades in high school, by his own admission, do not reflect his intelligence or aptitude. Client reports being a “lousy” and largely unmotivated student in high school: “I was pretty

crapadaisical [sic]

because I couldn’t see the point. Now I see the point. Jesus and Joseph, do I see the point.”

Client reports no history of arrests or substance abuse.

Client worked part time during high school at a number of businesses, including the following: Burger King, Von’s, Griffin’s Auto Repair Services, Subway, and Big O Tires. He enlisted in the U.S. Army during his senior year and began his service immediately upon graduating.

Client has never been in therapy.

EVALUATION METHODS

Review of Medical and Employment Records

Counselor Interviews

Standardized Assessments

ASSESSMENTS ADMINISTERED

American Identities Artistic Aptitude (Full Inventory) Assessment

American Identities Personality Inventory

American Identities Spatial Aptitude and Reasoning Assessment

American Identities Systemic Work Values Inventory

American Identities Vocational Aptitude and Interest Assessment, Advanced

California Psychological Inventory

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2

Novak Mental Status Examination, third edition

Otis-Lennon School Ability Test

Stennis-MacLean Anxiety Inventory

Strong Interest Inventory

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, fourth edition

Valpar Component Work Samples

VCWS01 - Small Tools Mechanical

VCWS02 - Size Discrimination

VCWS04 - Upper Extremity Range of Motion

VCWS10 - Tri-Level Measurement

VCWS12 - Soldering and Inspection

VCWS15 - Electrical Circuitry & Print Reading

VCWS17 - Pre-Vocational Readiness Battery

Valpar Whole Body Range of Motion

(For a full description of each assessment, see

Addendum B.

For the client’s individual scores for each assessment, see

Addendum C.

)

INTERPRETATION OF RESULTS

In terms of Guillermo’s general physical mobility and strength, he . . .

As far as Guillermo’s general intellectual skills go, he seems . . .

Guillermo’s grooming and dress were . . .

Results of the mental status assessment show . . .

His interests and talents coincide with . . .

The possible personality traits that might conceivably hold him back include . . .

Guillermo stated his vocational goals as follows . . .

In terms of Guillermo’s willingness and ability to resume life-threatening violence at the behest of his country’s major oil interests, he . . .

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Guillermo’s personal desire to discontinue active combat should be thoughtfully considered by the appropriate person or persons in charge. Even though there is nothing in Guillermo’s assessment that shows definitively that he is physically or psychologically incapable of continuing his duties as a soldier, the assessment is far from infallible, and the client’s own statement of preference should . . .

An examination of the Social Introversion subscale of the MMPI-2 may not seem noteworthy unless one adds personal observation to the analysis. The term

alienation

or

social alienation

is frequently . . .

It is within my purview to recommend a full psychological evaluation even though none of the assessments point in an obvious fashion to . . .

How does one assess the ability to continue doing that which no one should be asked to do . . .

Hell no,

he won’t go . . .

I have been asked to write—in the crippling language of this discipline—another man’s memoir, and end with a life or death recommendation. To do this, I need not only weeks of examination but something like an omniscient understanding of his psyche, and I would need the same all-knowing comprehension of the conditions of the war, and, for that matter, the reasons

for

the war. While I am accustomed to assuming this type of role, in terms of this client’s situation, I am feeling a tad uncertain or unreliable in this specific case, as if I have bitten off more than . . .

Guillermo Mendez is a man of integrity. He approached each of the assessments honestly, even though he had a private agenda (which he did not reveal until the exit interview) that could have been advanced by a dishonest approach.

I must not cheat,

Memo thought,

despite the dire circumstances of my life.

Even in the final interview, he did not reveal all of his thoughts, but you need to hear them before you decide to send him back to Iraq, and my measurements permit me to offer an articulation of those thoughts with a degree of precision that . . .

Jesus, god, help me write this thing . . .

DAY 11:

Over the weekend Maura read a book Barnstone had given her about a man who went to Alaska, deep in the sticks, and died there, and she got into a long, unbelievably tedious conversation with another girl on the at-risk floor about ways to release bad energy from your body (the girl had scars up and down her arms), and she read a second book Barnstone had dropped off about biologists measuring the beaks of finches to prove the theory of evolution. It didn’t sound like a page-turner, but she got into it, finishing it at three Monday morning, reading with her lamp under the blankets because it was way after lights out. A few hours later, at the sheltered workshop, the assembly butterfly jammed, and Billy Atlas could not get it to run. Maura wanted to roll out a cafeteria table and take a nap. Her work scores were shit without sleep, and the broken assembly machine seemed like a wish come true.

“You want it fixed?” Vex asked.

“Don’t let him touch it,” Maura said.

“Thanks for offering, Vex,” Billy said. “I appreciate your offer, but I need to make a call.” To everyone, he added, “You guys take a break.”

Billy had trouble, as he often did, finding the right key on the facility key ring, and before he could open the door to the office, Vex had the machine running again.

“Vex stuck his arm in the assembler machine,” Rhine said. “We’re not supposed to stick our arms in the assembler machine, Mr. Atlas, and Vex did.”

“Mr. Billy Atlas,” Alonso said.

“Just Billy, guys,” Billy said.

“It’ll jam again,” Vex said, having already resumed his relentless box assembly.

It did jam again, and this time it took Vex almost a minute to get it running. “Once I’m off the clock,” he said, “I’ll fix it permanent.”

It jammed twice more, and near the end of the day, it made loud rattling thumps, like gym shoes in a clothes dryer, and then an almost dental grinding. It smelled of burning rubber. Billy unplugged it.

“The only thing is take the motherfucker to pieces and put it all back together,” Vex said. “I need tools, a hookup, and some chicken or beef sandwich, no condiments.”

Resisting Vex’s offer once again, Billy Atlas pulled out one of the cafeteria tables and gave them each paper and a pencil. “Write a story,” he told them.

“Can’t we just sleep?” Maura asked.

“Not no but hell no,” Alonso said.

“What sort of story?” Rhine asked. “There are very many sorts of stories.”

“Whatever kind you like,” Billy said.

“I like different sorts of stories,” Rhine said.

“You’re going to have to tell him what kind,” Maura said. “Why are we writing stories?”

“I like stories,” Karly said, reaching out to Billy, who did not take the hand but patted her on the back. She reached around and patted him on the back, too.

“A fairy tale,” Billy said. “Here’s how it starts: Once upon a time . . .”

Remarkably, all of them started writing even though it was obviously busywork. Maura understood why they did it: they all liked Billy, even Vex. Who wouldn’t like him? He was like a tub of butter that even the meanest alley cat would lick.

Besides, there was only a half hour before the van arrived.

Maura retold “Little Red Riding Hood,” moving it to Minnesota so she could have some snow on the ground, which provided her with tracks in the white landscape, which tipped off Hood that the fathead wolf was in the cabin with her granny, and Hood peeked through the window (why don’t characters in stories ever shut the damn shades?) and observed Granny and Wolfy getting it on. Maura spent a paragraph describing this action explicitly, especially the wolf’s furry loins and wolfish cries, and then the van driver honked and she didn’t get to finish.

“It’s like we’re all dogs,” Jimmy said.

“We’re dogs now?” his mother asked, and at the same moment Billy Atlas said, “What kind of dogs?”

They were at the dinner table, Jimmy and Billy at the far end due to the filthy condition of their clothing. Pook had begun the meal with them but conversation had driven him away. He had taken his plate to his room: pot roast, yams, green beans, which was what everyone was eating except Billy, who would only eat boxed cereal, bread, pimento cheese, and potatoes. He had a bowl of Cheerios and a yam. May Candler insisted that a yam was the same as a potato. With his fork Billy poked the yam, which was the orange of traffic cones. There was no way he could eat a yam.

“Any kind of dog,” Jimmy said, “and we live by dog rules, like we jump around and flap our heads when other dogs come by and bark and play and chase each other and growl.”

“I don’t much care for thinking of us as dogs,” his mother said. “Couldn’t we be emu or something more elegant for your mother’s sake?” his father asked.

“Let him finish,” his sister said. Was she really there? Was it one of those rare nights when she wasn’t working or out with Armando Sandoval? Or had memory—Jimmy’s and Violet’s both—put her there, insisted that she had been present that momentous evening? The most true statement: she was both there and not there.

“I wanna be a Lassie,” Billy said. They had seen

Lassie

on Nick at Nite at his house earlier that week—they did nothing at the Atlas home but watch television since the Candlers did not have cable—and the boys hated the show, especially the apple-cheeked Timmy, but Billy refused to be prejudiced against the beautiful and amazingly well trained dog who could hardly be held responsible for the butt-stupid show. “What kind of dog is that?”

“A lassie is a girl,” Jimmy’s father said, and at the same moment Violet, if she was present at all, said, “Collie.”

“It’s just a comparison,” Jimmy said. “I don’t mean we’re really dogs.”

“What do you mean then?” his mother asked.

“It’s just that dogs see the world like dogs.”

“Thank you for that insight, son,” his father said. “Pass the yams.”

“I’m not done,” he said and passed the yams to his father. “Now I have to start all over.”

The groans came from multiple sources.

“Make us collies this time,” Billy said.

“I’m just saying that it’s like we’re all dogs, everyone here sitting at the table.”

“Can I still use my fork,” his father asked, “or am I meant to bend over my plate and . . .” He lowered his head and took a lick of the roast.

Jimmy and Billy laughed appreciatively.

“I rather like being a dog,” his father said, gravy sticking to his nose.

“You’re pandering,” his mother said.

“That’s disgusting, Dad,” Violet might have said, but she would have been smiling and would have laughed aloud after she spoke. One of her roles in the family—a wholly unconscious role, though one she relished—was defender of their father against their mother. In her supple hands, the part did not require her to turn against their mother, and most of the time, she merely used laughter to undercut the tension.