Tumbledown (29 page)

Authors: Robert Boswell

“He’s a sedimentary artist,” Billy had said, referring to their sixth-grade geology lessons. “You know, how sedimentary rocks can have layers of stuff. But he’s also kind of volcanic.” There was one other type of rock, but they couldn’t remember it.

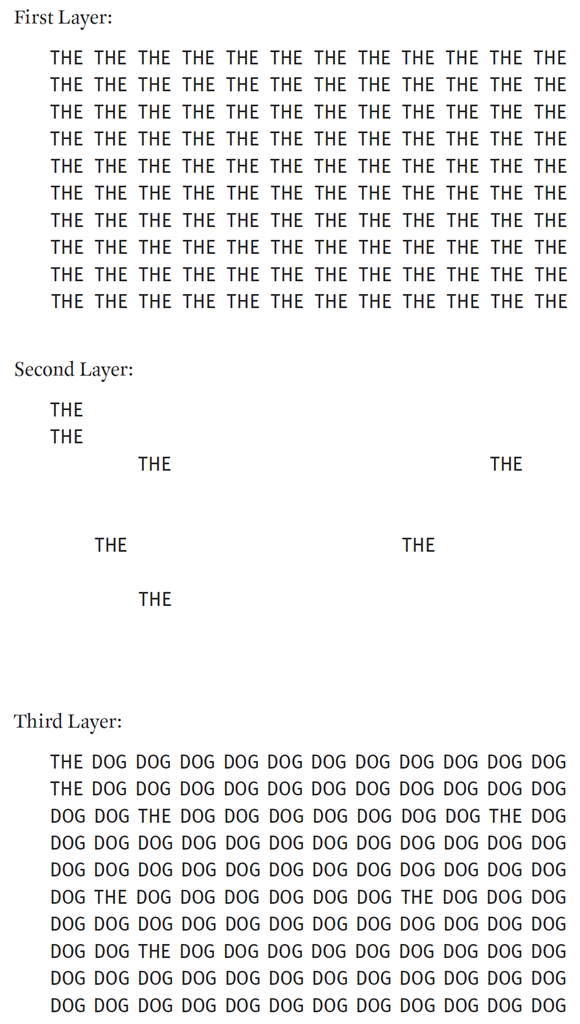

Jimmy thought Pook’s method of composition had to reveal something about him. Why did he have to paint the whole canvas pink in order to have that pink sun emerge when he failed to paint over it? It was like having a hundred guitars each playing a different note, and then mixing and silencing them sequentially to create a song. Or if you were writing a book, you’d have to write a single word over and over and over, and then cover most of the words with new words, and then cover most of the new words with newer words, until a story emerged. He got out the typewriter and Wite-Out from his dad’s study.

He gave up. He shouldn’t have started with THE. Pook always started with the deepest thing, and there was no way THE could be very deep. That meant you had to know what was deep before you knew anything else, which Jimmy didn’t know how to do.

Many paintings hung on the walls of the Candlers’ house, but not the paintings of Frederick and May. It was a point of honor not to hang their own work. They traded with other artists. Periodically, some came down and others went up. When Pook painted from the porch, the inside of the house became the setting for the portraits, and the paintings on the living room wall appeared in the background but they were transformed. Abstract paintings became representational, portraits became landscapes, and landscapes became flowers or wallpaper or slabs of meat. Pook painted everything from memory and each item was not merely altered but remade. Even the objects that were identifiable—the piano, for example—were made unspeakably odd, and Jimmy had not been able to say why.

“There’re no black keys,” Billy pointed out.

Frederick and May did not immediately trust their estimation of Pook’s work. They knew art and they had both taught for years, but this was their son and he was damaged. They were prone to compliment his few successes excessively. And this time it mattered in an entirely different way. If Pook was as talented as he seemed to be, the question of how he might spend his life was finally answered.

Frederick placed a few of Pook’s canvases in the station wagon and drove to Phoenix. He was acquainted with an art dealer who had connections to galleries in New York, Santa Fe, and Los Angeles. Frederick did not tell the dealer that the artist was his son but claimed the paintings were the work of a student. The dealer flipped for them. He sent slides to the owner of a New York gallery. Plans were made. The gallery wanted to stack the paintings three high on its walls and augment them with paintings on easels. Fifty versions of Pook staring at the customers. They set a date that gave Pook several months to finish the remaining portraits.

Pook was told nothing of the plans, and for days all he did was situate and re situate his easel, paint canvases brown, set up and take down his easel. Then one day he painted four canvases, and the next day, he painted three more. The following week, he had a day of seven completed pieces. He had more than fifty paintings by the time of the opening.

And still, Pook knew nothing. As long as he had a window seat, he liked to fly in airplanes. It was easy to convince him to fly to New York with his parents. They planned to stay at an inexpensive hotel in New Jersey that Frederick and May often used, but the gallery owner lived in the high-rise across the street from the gallery, and the three Candlers stayed in an apartment on the fifteenth floor owned by a family spending the year in Europe.

Violet was seventeen by that time, and she remained home to look after Jimmy and, of course, Billy Atlas, who was spending the night despite Violet’s protests. “Couldn’t you two spend one weekend apart?” It would be years before they would see pictures of the show, the paintings stacked like windows, one upon another, all of the images of Pook staring out, staring back. In every painting, the figure peered out directly, as if to look the observer in the eye. They were unnerving and powerful.

It was impossible,

one art critic would argue,

to say that one of Paul Candler’s pieces was better than another.

Some had background objects—trees, the house, a car, Pook’s idea of a horse or goat or pumpkin. There were never other people. In most, Pook was standing, but he squatted in some, reclined against a fantastically polka-dotted chaise, stood on tiptoes. There were no nudes, but his clothing changed, and most of it was either imaginary or based on his memory of actual clothing. For one shirt he painted dark blue trains against a yellow background, and Jimmy realized the shirt was modeled after a pajama top he wore, which had no trains but cowboys with lariats. He asked Pook about it, taking the pajama top to show him. Pook pointed to the raised lariat and its perfect circle of rope. “I remembered smoke,” he said. “That made a train.”

Frederick and May dressed up for the opening, but they saw no reason to ask Pook to change from his habitual jeans and T-shirt. He was the artist and eccentricity was expected. They ate first, bringing food to the room since Pook did not like restaurants. After the first few bites, he took his plate to the bathroom and finished eating there. They timed their entrance, as the gallery owner requested, to coincide with the height of the crowd.

“We have a surprise for you,” his mother said to him. “I know you don’t much care for surprises, but this is one you’ll like, I promise.”

At first, it did seem that he liked it. He ran in a quick circle around the room, his head turned up at the paintings. He knocked one patron to the floor and splashed wine on another. “This is the artist,” the gallery owner told them, and even the knocked-down man laughed it off. This part of the story, Jimmy and Violet pieced together from their parents’ accounts, and they had not thought to wonder about the detail of the man laughing until later when they discovered how the paintings had been marketed. Pook had been offered up as something of an idiot savant.

When Pook finished his lap, he walked out the door. May ran after him, leaving Frederick to explain. The opening was a mild success, but the show would turn into a fantastic triumph the next day when the world learned that the artist had leapt from a balcony on the fifteenth floor to the sidewalk, dying on a spot directly across from the windows of the gallery, expiring under the gaze of his creations. The paintings were snapped up quickly, and the gallery owner would one day admit that he should have raised the prices but the death had so befuddled him that he’d missed the opportunity of a lifetime.

What Violet remembered most was Jimmy’s reaction when she told him Pook was dead. She had been watching a movie when their parents called, and she had not wanted to answer the phone. Her mother’s voice trembled when she spoke. Violet leapt up and turned off the television. She was crying when she called her brother into the living room.

“Pook’s dead,” she said. “He jumped out a high window.”

Jimmy dropped to the floor on his bottom, simply sat on the rug with a thump. He was not crying but staring off into space. Billy, who had come into the room with him, got down on his knees to put his arms around his friend.

“Mom said the exhibit upset him,” Violet told him, kneeling next to her little brother. “He didn’t know what he was doing.”

“Pook always knew what he was doing,” Jimmy said.

“Not this time,” she insisted. “He wouldn’t have killed himself if he’d known.”

Jimmy shook his head. “He didn’t like people seeing him. Seeing him in the pictures. Seeing so many of him. All of him.”

Later, Jimmy cried in her arms, but it was this conversation on the floor that stuck with Violet, how the boy was so utterly certain about his brother’s indecipherable act.

Candler remembered it differently. He and Billy had been in Pook’s room while Violet watched television. They were playing a narrative game, a running dialogue, where one and then the other would invent plot. The secret treasure—the narrative always included a secret treasure—had to be in Pook’s room, they reasoned. They were not normally permitted to enter his room, and so it only made sense that the elusive treasure was in there.

Unlike the rest of the house, Pook’s room had no paintings, nothing on the walls but scraps of lined paper, taped in place, in even intervals. The scraps were all at the same height. Nothing was written on the bits of paper. Pook’s dresser was neat and his desk was clear of clutter. In his closet were empty hangers on the rod, and below, a neat stack of pants and shirts on one side, and a neat mound of dirty clothes on the other side.

They found the treasure between the mattress and the box spring. Jimmy held up the mattress, and Billy pulled it free. A painting. The painting on the large canvas that Jimmy and Billy had stretched. Unlike any of Pook’s other paintings, it was set in the very room in which they stood. It showed the pieces of paper on the wall. In the painting, each scrap held letters:

mon, two, wen, thrus, fry.

To show all the scraps, Pook had painted his body only in outline, a ghostly absence. There was something about those painted pieces of paper, how the whiteness of them seemed to vibrate. They were the deepest layer, the gesso that covered the canvas before any paint was added.

Then the phone rang and Jimmy’s sister shut off the movie and began to cry.

The boys did not show the painting to Violet. They did not show it to anyone. They hid it, first in Jimmy’s room and later at Billy’s house. It hung now in James Candler’s office. It was the only one of Pook’s paintings that any of the family still owned.

And years later there was a night when James Candler was in bed with Saundra Dluzynski, asleep beside her, dreaming that he was a boy and wearing his cowboy pajamas, which had transformed into a shirt with a pattern of trains billowing steam. And both Jimmy in the dream and the sleeping James in bed would recall how Pook’s head was angled in that painting, and in his left hand there was an object—a ball? an apple? What had he held? Candler shifted in bed, rolling his head along his pillow, half awake. And then he woke with a start: a pine cone. Pook, in that self-portrait, held a pine cone as if he was ready to toss it. The tiny clouds of steam on the shirt. The trains. The lariats. The bicycle without a seat. The scraps of paper on his wall. The big brother who goes away on a trip and never returns. What made Pook different from other people, Candler realized, if vaguely, as if he were still dreaming, was that Pook was just one person, and always the same person, and all those images of himself made it impossible to continue with his single life. Yes, Candler thought, at last that mystery . . . but he drifted off and lost forever the thread.

Billy Atlas remembered one other detail from the night Pook died. When Jimmy fell to his butt on the carpet and Billy went to his knees to put his arms around his friend, Jimmy whispered, “We didn’t save him.”

Once Pond a Time

Even the gods cannot change the past.

—AGATHON

She killed the car. She had stopped again at the tiny local museum to sit on its porch, peer through the darkened windows, and compose herself. She had not expected America to be so utterly unchanged when she had been through so much. Only her name was the same. She had kept her maiden name when she married, and she carried it now as a widow: Violet Candler. She was thirty-eight years old, and her husband had been twenty years older, which meant they had expected him to go first. Just not so unreasonably soon.

She climbed from the ugly, dirty, decrepit, perfectly adequate car, and returned to the comforting porch. She had her brother’s cell phone, which meant she could not think of herself as lost so much as misplaced. The party in their honor—hers and Lolly’s—was going strong and she would have to return, but she’d also had to escape it for a while. She enjoyed parties, generally, but not with loud, bad music and dozens of strangers, all wanting to shake her hand and tell her how much they liked Jimmy yet having nothing real to say about him—or perhaps nothing they were willing to say. He was evidently in line to become their boss, and they were careful, which rendered them tedious.

The porch was modest and tidy, its painted wooden planks solid under her shoes. Through one of the black windows she made out an enormous wing, rising from a great and oddly shaped body. She wondered about the nature of this museum and the treasures the house might hold. A fantasy of strangeness presented itself but vanished when she realized she was staring at a piano, a baby grand, its black lid raised as if to fly away.

She had left the party with the excuse of going to see the Congregation of Holy Waters Museum, and though she had tried to follow her brother’s directions, she had gotten lost. She only managed to find it because Jimmy said it was practically under the freeway. It was impossible to drive in Onyx Springs without running into the freeway, and she tried every exit until she saw the modest blue sign for the museum. It was closed, of course, but she parked and examined the old building. The only part of the evening she genuinely enjoyed took place in the squeaking porch swing.

She had driven off to return to the party and didn’t know how thoroughly lost she was until she realized that she was driving by the museum again. After circling for half an hour, she was back on that tempting porch. The swing was soothing and the interior of the car smelled bad. Out in the relative dark, she could ignore, for the moment, her navigational incompetence.

The car was not hers and not her brother’s. A rust-laden ancient Dodge Dart, it belonged to Jimmy’s hapless friend Billy Atlas. It was the only car he had ever owned, a fact that struck her as deeply pathetic. He had driven it since he and Jimmy were in high school. On the one hand, she admired her brother’s loyalty to his friend; on the other, Billy Atlas was an incompetent. She didn’t dislike him, exactly, but she never looked forward to seeing him.

They were all, for the moment, living together in Jimmy’s house: her brother and his fiancée, Billy Atlas, and Violet. The house was fairly new and (thankfully) had plenty of bedrooms and Jimmy kept it clean, but it was a drafty, unattractive barn that managed to be ostentatious and cheap at the same time. Why Jimmy would buy such a place baffled her. He owned a fancy automobile, as well. It was a pretty object, much the way an ashtray might be pretty, but why would he spend a fortune on a car?

Jimmy had changed. They had been close when Violet was in college and Jimmy in high school. She had driven home regularly to see him, and they phoned twice or more each week, talking about the people they were seeing, their colorful array of lovers. They had been frank about sex and desire and the attendant feelings of uneasiness and fear, but their real topic had been the future, what they were going to do, how they were going to make their lives interesting and bold—

meaningful.

They planned to have meaningful lives. Their conversations bolstered her when she decided to live in Europe. She left for England young and excited and full of the electric heat of possibility, and now she had come home, her youth spent, her husband dead, and her brother was neither the friend he had once been nor any man she knew.

Oh, she missed Arthur. Not the way he was at the end. She was not sad to see that final, diminished version of him disappear. She missed the man she had married, the gentle, absentminded man who wanted nothing more from life than to spend it with her. She flipped open Jimmy’s cell with the intention of calling him. Only while she was examining his contact list did it occur to her that, of course, she had

his

phone. Who was she meant to call? Ideally, it would not be someone at the party. She didn’t like the idea of her ineptitude becoming a joke to pass around like a bowl of dip. She had only been back in the States for ten days, and she wasn’t ready for even a minor humiliation. Unfortunately, Jimmy’s contact list was merely first names. Lolly was one of the few she knew, and she was the last person Violet wanted to call for help. She had inadvertently introduced Jimmy to Lolly, and there were few things in her life she regretted more.

Lolly Powell drove her mad. She was a woman who shaped her identity to fit the immediate circumstances of her life, a talent she must have discovered at some point in her youth, and she clearly had never gotten over the astonishment of her adolescent success. All of which left her bereft of an actual personality. She simply did not make sense as a person. She was an enormously competent child, and now she had no outlet for that competency except as it concerned Jimmy. They were in that stage of romance where they could not keep their hands off each other, which meant Lolly spent her time being a sex object, and Violet had to admit that she was terribly competent at it.

Terribly competent.

Violet had almost changed her plans to stay with her brother once she understood Lolly was coming, too. If her parents hadn’t divorced she might have gone to Tucson.

More to the point: Lolly’s cell, like Violet’s, didn’t work in the U.S. She didn’t particularly care to ask Billy Atlas for help either, but he, at least, would be discreet if she requested it of him, and his was the only other name on the list she recognized.

The call went directly to voicemail: “This is Billy to the B—” She ended the call, folding her arms over her chest and pushing with her toes to rock the swing. She was going to have to call a stranger.

As she thought this, something brushed against her leg. She stopped swinging and shifted her feet. She felt it again and lifted her legs, folding them onto the swing. Her heart hurtled beyond reason into something resembling terror. The open phone provided a nimbus of light, and there on the painted planks was a cat, a tabby, her head cocked away from the phone’s illumination.

“You gave me a scare, kitty,” Violet said, lowering her feet slowly, displaying her free hand in the phone’s light as she neared the cat. Curling its head to accept the offering, the cat revealed the opposite side of her feline face, which was matted with blood. Violet startled and the cat bolted. She called after it apologetically, but the opportunity had passed.

One of the entries on the phone’s contact list had

at home

written after the name, and she tried that one. At least, if he answered, he definitely wouldn’t be at the party.

“Coury residence.”

“Is this Jimmy Candler’s friend Mick?”

A long pause ensued and then a tentative “Yes.”

“I’m terribly sorry to bother you, but I’m Jimmy’s sister and I know it sounds ridiculous, but I don’t know my way about Onyx Springs and I’m lost.”

“You need directions?” He asked for her location, and she told him. “I’m trying to get to a bar . . .” She realized that she could not recall the name of the place. “It’s out on a highway . . . I . . .”

“I can be at the museum in five or five and a half minutes,” this Mick Coury said. “If you don’t mind the porch? If it’s not too dark.”

“I like the porch.” She almost added that she liked the dark and winged things hidden inside, the dark and damaged things that prowled the deck, but she held back. She already sounded stupid; she didn’t want to sound crazy.

Mick had been upstairs, barefoot in his bedroom, shifting his weight experimentally from one foot to the other, when the telephone rang in the hall. He went to get it. His mother didn’t like to answer the phone if both her boys were in the house. The two greatest inventions in the history of humankind, she liked to say, were the answering machine and disposable diapers. “What about the wheel?” Mick had asked her.

He had a plan for the evening: hanging out with Maura at the only place she was permitted to hang out—her dormitory. Not in her room. Boys couldn’t go to the girls’ rooms because they might layer together in a dormitory bed and ladle kisses along the length of their bodies. On the ground floor were Ping-Pong rooms and board games and a TV like a great rectangular mouth—no eyes or nose, just the mouth, as if instead of mounting the head on the wall, the taxidermatologist had cut everything away but that enormous mouth, which hung on the wall and people stared into it, the monster’s immense mouth, from which no one could look away.

He had showered. He had toweled off. He had rubbed the towel over his hair briskly. He put on black socks but felt funny naked in black socks and took them off. He combed his hair. It was still damp, and he toweled it again. He rolled deodorant on his pits. He couldn’t decide whether to put on the shirt first or his underpants. How do people make such decisions? What is the underlying basis for such decisions? He went with the underpants. He put on the same black socks, but they sheathed him from the carpet’s sly tickle. He took off the black socks. He sat on the edge of the bed and simultaneously lifted his legs while with two hands he waved the pants. He shot his feet into the pants’ oval openings.

Who says he puts his pants on one leg at a time like everybody else?

He was buttoning his shirt and thinking about balance, the carpet licking his bare soles, when Mr. James Candler’s sister called to ask for help. Such an unexpected call, but it had been a day for the unexpected. For one thing, Maura finally got to ride in his Firebird. “Thank god your brain wires fried,” she said upon climbing in. “You were definitely an asshole before.”

He had taken her to lunch. She wasn’t supposed to go anywhere without an official chaperone, but Billy Atlas gave her special permission to ride with Mick while he ferried the others to KFC. Maura’s diet didn’t permit fast food, and Mick escorted her to a diner. That was another unexpected thing, eating at a diner, whose chairs had padding and silver legs, and the utensils were not made of plastic. Also, Karly had all day not wanted to make wedding plans with him. Could something be repetitively unexpected? Routinely unexpected? A daily unexpected thing that he could count on?

After he finished talking to the lost woman, he reunited phone and receiver. He put on his socks and shoes. He didn’t examine himself in the mirror, which always took longer than anyone might suspect. He couldn’t afford the time when there was a woman waiting for him, a stranger who needed assistance. Had Mr. James Candler advised her that Mick was the one she should call if she strayed off course? What other answer could there be?

Downstairs, he dipped into the living room to say good night to his mother, who was spread over the couch buns like a condiment. The room would have been dark except for the television, a black-and-white movie offering a shifting, grumbling light. His mother wore sweatpants and a T-shirt, her after-work uniform. Today’s T-shirt was red with yellow lettering: I CAN RESIST EVERYTHING BUT TEMPTATION. He knew that was funny, though it didn’t make him laugh. Her eyes left the screen long enough for her mouth to say, “Call me if you’re going to be late.”

“I’ll call you if I’m going to be late,” he replied.

She looked at him then. “You didn’t comb your hair.”

Mick ran his fingers through his hair, the ravines between tingling much the way his bare feet had against the carpet. He counted backward from twenty to appease her, to prove that he had taken his meds, which he hadn’t. Not a whole pill, anyway. His mother had read an article in a magazine about how to tell if a person was crazy: have him count from twenty to zero without a mistake. Only people not at the moment out of their minds could do it, evidently. Mick could do it. Sometimes he got the perfect amount of medication in his bloodstream, and tonight was such a sometime. He felt light and alive and free, and not in danger of levitating out of it. Firmly rooted and all that.

“All right, I suppose,” his mother said. “Have fun.”

The reliable Firebird roared to life. On the way to the diner, Maura had told him that he drove at a

glacial

speed. That had made him laugh. The lunch had gone well until near the end. The waitress, her short sparse hair like electrical filaments, had said, “How does every thing taste?” Mick considered how humans tasted things, and how animals had specialized tasting abilities, and how every creature, even something such as a halibut, which was what he’d been eating, must have the ability to taste, and how did the hook taste when it bit into the fish’s mouth? He could not answer, staring dumbly at the waitress, but Maura saved him.

“Z’all great,” she said.

How it was possible that he could not come up with such a simple, generic line? A waitress was not interested in philosophical truth-saying. She was checking in, being polite, protecting her tip. It seemed to him that all he needed to do was memorize a few rote sayings, latch on to a handful of clichés, and he’d be sane.

“Have a nice day,” he practiced as he steered, not zipping along as he would when he had taken no meds. Sane driving, though slower than any other car on the road. “Take care,” he rehearsed. “Keep your head up.”

The Firebird ducked under the freeway’s dark awning and just beyond, the unlit museum crouched by the side of the road. The car in the lot was older even than his own, and he felt a sudden kinship with this mislaid woman. A shadow on the porch rose from the swing and descended the steps, gaining color and human dimensions as she approached, shedding her shady existence, utter transformation. How magical life was when you really saw it. She had blond or maybe light brown hair, a willowy build, a woman older than Karly or Maura, but no older than his mother. He got out of his car to greet her.