Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea (11 page)

Read Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea Online

Authors: Adam Roberts

‘And you think we have sunk into this legendary space?’

‘Legends are rarely invented out of nothing, my friend,’ said Lebret, gravely. ‘They are invariably based upon facts, race-memories, primordial truths. Often distorted and embellished of course, but at their core is always a truth.’

‘This crack, or chasm – you believe it to be a literal feature of the world?’

‘Literal,’ said Lebret, a more characteristically ironic gleam entering his eye, ‘is a very dull and materialist word for a Hindu to use – don’t you think?’

‘I am trained in Western material science, after all,’ Jhutti replied, smiling. Then, in a low voice he added, ‘Cloche will never agree to use his vessel to explore this new ocean. Never. He wishes to go home, and nothing else.’

‘I fear you are right,’ agreed Lebret. ‘But perhaps he can be persuaded? The possibilities, for science I mean … they are unprecedented!’

‘Does he seem to you the type of man who can be persuaded? Of anything?’

‘No,’ Lebret conceded, wearily.

The two sat in silence for a long time.

‘Surely de Chante must have finished working on the vanes?’ said Lebret. ‘Let us go and see what the situation is.’ And so they walked along the shallowly-angled corridor and through into the bridge.

But there was no sign of the diver. Fifteen minutes became twenty, and Boucher’s agitation grew. ‘I’m getting,’ he complained, bunching his hands into fists and unflexing them again, ‘these

spasms

in my hands. Is anybody else getting that?’

‘Where is our diver?’ asked Lebret.

‘Nobody knows.’

Half an hour passed.

‘Spasms in my hands,’ the lieutenant complained, vaguely. ‘And where’s de Chante? Where has he

got

to? He should be back by now. Are the forward vanes working now?’

‘No, Lieutenant.’

‘He’s gone,’ said Lebret.

‘Hush!’ pleaded Boucher, making alternate starfish and ball shapes with his hands. ‘Don’t say so!’

‘Gone,’ repeated Lebret. ‘It’s true.’

‘There must be some way we can see what he’s up to – does he show up on the sonar?’

‘I’m not sure the sonar’s even working, Lieutenant,’ reported Le Petomain. ‘It has returned only blankness since we began our dive. But even if it

is

working, a diver swimming close about the hull wouldn’t show up on it – unless he passed directly in front of the sensor, perhaps.’

‘I’ll have a look through the periscope,’ Boucher announced. ‘Somebody go down to the observation room – open the shutters and see what you can see.’

‘I’ll go,’ said Billiard-Fanon. He stomped, scowling, down the corridor.

Boucher clambered up into the con. They heard the miniature whir of a servo, as the periscope deployed and began to rotate. ‘It’s dark,’ he called, a little superfluously. ‘But de Chante has a light on his helmet, doesn’t he? I should at least be able to see that.’

They waited.

‘He must be beneath the vessel. Le Petomain,’ Boucher called down through the open hatch, shortly. ‘There’s nothing up here – I ask you to roll the ship a little, and also to pitch her back and forth, so I can see more.

‘The vanes are stuck, Lieutenant,’ the pilot replied. ‘I can pitch by shifting air in the ballast tanks, but the manoeuvres will be a little stiff; and rolling the vessel is beyond me.’

‘Let’s start by pitching forward a little.’

Slowly, the

Plongeur’

s whale-shaped nose dipped forward in the water; and the men in the observation chamber braced themselves. The walls of the vessel groaned mildly. The floors slanted forward once more.

For a moment there was nothing. Then, abruptly, there was a clatter from below, and Billiard-Fanon clambered up the hill and into the bridge. His big face was sweating.

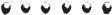

‘Light!’ he cried. ‘Below us – light!’

‘What?’

‘I didn’t see to begin with,’ said the ensign, gruffly. ‘It’s not visible when the ship is lying flat. I opened the shutters, turned the lights off and smoked a cigarette. Nothing to see. But then – the vessel pitched forward, and …’

‘You saw de Chante’s light?’

‘What?’ Puzzlement gave Billiard-Fanon’s long, jowly face an idiot look.

‘De Chante,’ said Castor. ‘You saw his helmet light?’

‘There’s no sign of

him

. I’m talking about

the light

! God has not abandoned us! Come and see!’

Billiard-Fanon led Lebret, Jhutti, Ghatwala and Castor down

into the observation chamber. The angle of the corridor meant that they had to pick their way with some care.

‘There!’ said Billiard-Fanon, triumphantly.

At first – nothing. But then, slowly, unmistakeably, a mauve-blue gleam was nebulously but unmistakeably visible at the bottom of the viewing portal.

‘Light,’ breathed Billiard-Fanon.

‘We can all see that, I presume,’ said Lebret. ‘Yes? That rules out the notion of hallucination. There is

something

shining down there.’

‘But what?’ asked Castor.

The light possessed some strange aspect – a deathly, or more precisely a life-in-deathly quality to the hue. A chill blue. An antithetical blue – purple-black and uneasy.

‘We must inform the captain,’ said Billiard-Fanon.

‘Yes,’ said Lebret. ‘I think we must. When he sees this, he will understand – understand that we must go further down and investigate!’

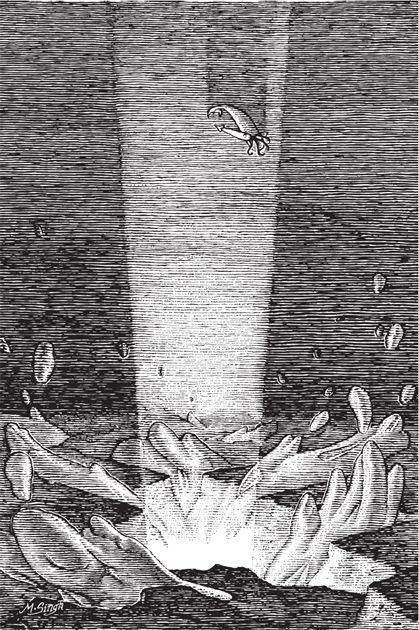

Boucher tapped gingerly at the door of Cloche’s cabin and went inside. Four minutes later he re-emerged. The captain followed him. The old man had not, by the look of him, been sleeping. Indeed, his beard appeared even more massy and spread-out than before – almost as wide as his broad chest, covering three of the four brass buttons on his jacket, as thick as a beaver’s tail. Cloche had fixed it to his shirt with a tie-pin – of all things. Cloche’s eyes were fixed, stern, the signals of a set and implacable will. ‘My lieutenant says there is a light in the water.’

‘Indeed, Captain!’

‘Messieurs,’ he said. ‘I am

also

told that we have lost de Chante – lost at sea. Is it so?’

‘It appears so, Captain.’

‘A brave sailor,’ Cloche growled. He seemed to have forgotten that only hours earlier he had called the fellow a coward. Nor did he seem unduly distressed by the loss of one of his crew. ‘Did he fix the vanes first?’

‘No, Captain.’

Cloche tutted. ‘A malfunction with his apparatus,’ he said. ‘Clumsiness? An accident? Or perhaps there truly

are

dangerous currents in this sea. It is a great shame. And what of this light you say is below us?’

‘It is, I think, distant. Blue-white.’

‘Well! Well! Show me!’

Boucher led Cloche down to the observation chamber, with a half dozen others following behind. The captain peered through the broad porthole at the weird, vague illumination. ‘Very pretty,’ he announced. ‘And?’

Nobody said anything for several long seconds.

‘Perhaps we ought to investigate, Captain,’ said Jhutti, eventually.

‘Just so,’ agreed Lebret. ‘We

must

descend further, and see what is causing this light.’

‘No,’ said the captain, without hesitation. He pointed a finger at Boucher. ‘I gave orders that we were to ascend. Why have we not done so?’

‘The forward vanes remain to be fixed,’ said the lieutenant, in a tremulous voice.

‘If they cannot be fixed, then we must ascend without their help. Fill the ballast tanks fully with air. Angle the propellers. The ascent might not be as smooth as we would like, but ascent is the order.’

At these words, Lebret laid a hand on the captain’s arm. Cloche glowered at him, and he removed the hand. Lebret smiled with his usual supercilious insouciance.

‘Surely, Captain,’ he drawled. ‘Surely we could spare a

few

hours – to descend a little deeper through this strange medium, and discover the cause of this light? Science would honour you as its discoverer …’

‘I am not interested in the accolades of Science,’ replied the captain, abruptly. ‘Science can conduct its own investigations. I am interested only in returning my command to port.’

‘But to have come so far – to within touching distance of a mystery hitherto unsuspected by …’

‘When

we have returned to the surface,’ interrupted the captain,

forcefully, ‘I shall submit a full report. I have no doubt that the French Academy of Science will sponsor a – properly equipped – scientific expedition. It will surely be a simple matter to retrace our steps. But this – Monsieur Lebret –

this

– messieurs all – is not

our

business.’

He took hold of his magnificent, immense beard with two hands, and gave it a mighty tug – as if, by this emphatic physical gesture to forestall any and all disagreement.

Lebret, though, persisted. ‘No, Captain, I must register my disagreement. After everything we have been through – to miss this opportunity? It would be like a nineteenth-century explorer travelling through immense hardship to within two hundred yards of the North Pole and then giving up and going home.’

Cloche turned his steel eye towards Lebret. ‘You must

register your disagreement

, must you Monsieur?’ he said, in a level, voice. ‘Consider it registered. Consider it simultaneously disregarded. We return – as soon as the vanes are fixed.’

‘Monsieur Captain …’

‘No, Monsieur! No! The

Plongeur

suffered triple malfunctions simultaneously … either through sabotage, or perhaps through some design flaw. It is not safe,

not

a safe vessel to embark upon further exploration. We must return to port, sir. I order it.’

Lebret persisted. ‘What if the light and de Chante’s disappearance are connected? What if he is

down

there? Ought we not at least to investigate?’

‘Monsieur,’ said the captain, addressing himself to Lebret. ‘Speak again, so as to contradict my order, and I shall confine you to your cabin. Monsieur de Chante is dead. He is a hero of France, and shall be honoured –

when

we return to port.’

The scientist in Ghatwala spoke up for Lebret’s suggestion. ‘One hour, Captain!’ he pleaded. ‘Delay the ascent by one hour – to give us time at least to

observe

this phenomenon!’

‘And to give de Chante a little more time to return to the airlock,’ put in Boucher. ‘If he is able.’

Cloche glared at them, one after the other. ‘I sniff

insubordination

,’ he said, in a steady voice.

‘No sir!’ Boucher yelped. ‘We follow your orders, sir! It is only a question of whether we do so immediately, or whether you can permit us one hour to prepare for …’

‘Half

an hour,’ said Cloche, thunderously. ‘That is all!’

AN INTERVIEW WITH CAPTAIN CLOCHE