Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea (34 page)

Read Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea Online

Authors: Adam Roberts

‘I am to be addressed as the Holy One,’ boomed Billiard-Fanon. ‘And my actions in shooting you were directed by God himself.’

‘Is that so?’ Lebret returned. His elation at being able to speak again to the

Plongeur

had pushed his feverishness to the back of his mind; but his hands were trembling nonetheless, and his head, jaw and throat burned and ached. ‘Well in that case, I suppose my

survival

must have been directed by God himself too. It was certainly against the odds. And here I am, inside this chamber, speaking to you on a piece of technology that would make us all rich, if we could carry it back to France and sell it.’

‘Are you alive?’ Billiard-Fanon mused. ‘Or are you a delusion – a devil, sent to trick us?’

‘You’re the Holy One,’ Lebret creaked. ‘

You

should know.’

‘You speak like a devil,’ Billiard-Fanon announced.

The others seemed less persuaded by this quasi-religious explanation. ‘What other kit is there, down there?’ Castor asked. ‘Anything interesting?’

‘Come and see,’ Lebret said. ‘But bring the vessel’s first-aid box with you. I have a fever, and need penicillin.’

‘How are we to get to you?’ Pannier asked. ‘Some bastard stole the only remaining diving suit.’

‘That was me – that was how I got here. Look – are you in the observation chamber? What can you see?’

‘I’m there,’ said Castor. ‘I can see a faint light, and … well, it certainly looks like a giant shell.’

‘That’s because it

is

a giant shell. Dakkar probably modelled

it directly on Botticelli’s

Birth of Venus

. It contains a device, or perhaps it only

focuses

the device’s beam – and that has been drawing both us and the iron of the

Plongeur

down here. This is the end of the line, as the tram drivers say. Castor – can you see the source of the light?’

‘A circle, I think.’

‘Yes! That is a hatchway. Even without diving gear, if you take a deep breath you can swim easily to it; and through it is plenty of air – and food. Food!’

‘And drink?’ Pannier asked. ‘A good Côte du Rhone? A little rum?’

‘Listen,’ said Lebret, tucking the communication slate under his arm and pulling his shivering body along the corridor. ‘Look, I’m going to open the hatchway and put my head out.’

‘And flood your compartment?’ Castor asked.

‘It’s zero-g, it’s a cosmos of water – it’s a waterverse—’ Lebret gabbled. It was hard to distinguish the sense of elation from the giddiness of fever. He felt as if his whole body were a helium balloon. ‘Weightless, weightless. A little water spills in, but not – look here I am.’

He did not stop to consider whether the communication slate might or might not be waterproof; he simply opened the hatch and poked his head through.

It took a moment to adjust, of course, but even without goggles it was easy enough to see the

Plongeur

. Indeed, it could hardly be missed – a massive tube of metal lying on its side and filling most of the vast shell-shape. Lebret blinked, halfway along he could see the rip in the vessel’s fabric – the mess room – and nearer the hatch was the oval porthole of the observation chamber. A pale shape, like a dab of white paint in the middle of a painter’s nocturne, was Castor’s face, pressed against the glass. Lebret waved, but as Castor lifted his arm to wave back Lebret had to pull himself back inside the corridor to breathe.

‘I saw him!’ Castor was saying. ‘Lebret – I think it truly

was

him.’

‘You

think

?’ came Pannier’s voice.

‘His face is all swollen. But – I guess if he was

shot

in the face …’

‘I have prayed!’ boomed Billiard-Fanon, suddenly. ‘And God has answered me. Bring out the heathen.’

‘Who do you mean—?

‘Jhutti!’ snapped Billiard-Fanon. ‘

He

shall swim the waters. If he lives, as Lebret says he will, then perhaps we shall follow him. But we will watch from the observation chamber, and see whether this is all the devil’s trickery.’

Lebret clutched the communication slate to his chest. He was shivering more violently now, and the fever was mounting in his head. The whole right-side of his head was pulsing and throbbing. It was intensely uncomfortable. ‘Send Jhutti, by all means,’ he said. ‘But tell him to

bring some penicillin

with him!’

Presumably there was a delay whilst Jhutti was brought out from whatever cabin he had been held in, and forced or cajoled into the airlock; but time was becoming harder and harder for Lebret to grasp. The voices of the various members of the

Plongeur’

s crew mingled and jarred against one another. Only when somebody – Pannier, it sounded like – cried ‘he’s out!’ and Billiard-Fanon demanded impatiently, ‘Where? Where? Oh! I can see him!’, did Lebret pull himself together.

He stuck his head back through the hatch and into the water. A shape was kicking and arm-stroking through the waters, like a man half-swimming, half-walking along the bottom of a swimming-pool: Jhutti! Lebret reached out one trembling arm, and the scientist seized it. It was a simple matter drawing him into the tube.

‘It’s true!’ Jhutti gasped, as he sucked at the air. ‘It’s a structure – a corridor, and filled with air.’

‘Is that you, Jhutti?’ Billiard-Fanon demanded. ‘Put your face back up, so we can see.’

Jhutti twisted about in the corridor, and thrust his upper portion back into the water. When he drew himself back into the corridor, Lebret grabbed him. ‘Medicines, medicines!’ he begged. ‘Did you bring any?’

Jhutti shook his head, and tiny droplets of moisture left his

beard to float away. ‘They did not give me anything to bring,’ he said. ‘I am sorry.’

‘Billiard-Fanon’s shot wounded my jaw,’ Lebret explained, muffling the words and shaking. ‘I fear the wound has become infected. I must have medicine!’

‘You do look ill,’ Jhutti agreed. ‘And I am sorry for it.’

Voices from the communication slate made it clear that the others were about to leave the airlock and swim across too.

‘I am sure one of the others is bringing the first aid box,’ Jhutti said, unconvincingly.

‘I hope so,’ shuddered Lebret. He took as deep a breath as his tightened airways would allow, and stuck his head back into the water.

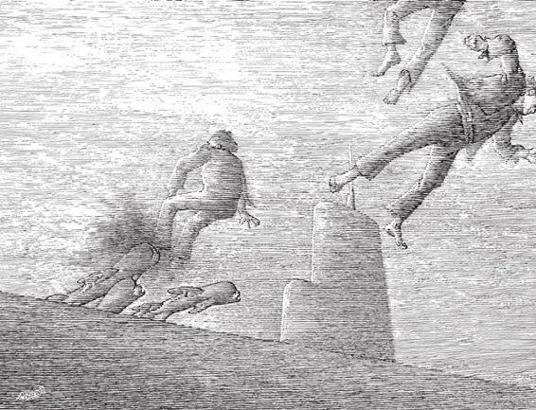

Blink, blink, and he saw the whole scene in wavery but discernible fashion. Billiard-Fanon was in front, swimming with strong kicks of his leg and coming straight for the hatch. Behind him was Capot, and behind him Pannier. There was no sign of Castor.

Lebret, looking back at the

Plongeur

, saw what happened next before anybody; but there was nothing he could do to warn the others. From the rip in the metal flank of the submarine, a shape swam out; and it was followed by another, and then another. Childranha. Even in his feverish state, Lebret immediately understood what had happened. As the

Plongeur

passed by the second sub oceanic sun, some of the creatures must have gone inside the flooded mess hall. And why not? There was food in there, and Lebret had good cause to know how hungry the beasts were – for protein, and also for oxygen. As the vessel sank away from that sun, and oxygen levels in the surrounding ocean sank to nothing, the childranha would not have been able to leave that little cell of oxygenated water, even if they wanted to.

But they were leaving it now. Lebret tried to signal, waved his arm with the absurd slowness of all underwater motions. That, or the expression of evident terror on his swollen face, alerted the three sailors. They looked round, and saw the monsters speeding towards them. Each reacted in his own way.

Billiard-Fanon smiled. It was unmistakeable. He crossed himself, and resumed his swim. He did not even hurry his motions, as if perfectly confident that God would protect him.

Capot writhed and kicked, wasted energy and time in a panicky wrestle with empty water, and finally struck out as fast as he could for the hatchway. The leading childranha-fish overtook him easily, and sank its fangs into his shin. The young sailor opened his mouth and vomited out a perfect sphere of air; but where his foot had been was only a spreading mess of red liquid coiling through the clear water, and the first childranha was swimming left with a boot in its mouth. A second childranha darted in and bit into end of the severed leg.

Of all of them, Pannier’s reaction was the most rational: he quickly assessed the threat, estimated the distance still to swim and balanced it against the distance back to the airlock, and immediately doubled back. He swum with large, strong thrusts of his legs and his arms and was back at the submarine before the childranha got to him. If he had been able to get the door smoothly open at first go he might have lived; but his fingers fumbled at the catch, and there was a flurry of childranha lurched at him, and then his arm was separate from his body and floating away to the side, trailing flossy strands of blood.

Billiard-Fanon was at the hatch. He pushed past Lebret, and ducked inside, disappearing with a wriggle.

Lebret looked back. Capot kicking and thrashing his arms, stirring up a cloud of dark around him – his own blood – as two childranha worried at his body. It was hard to make out exactly what was happening to Pannier, but certainly he had not made it back inside the submarine.

Somebody was tugging on Lebret’s legs. In the zero-gravity this slight pressure was enough to drag his body down. He slid out of the water and into the air, gasping. ‘Close the hatch, you idiot!’ Billiard-Fanon was yelling. ‘Close it!’

Lebret wanted to say:

we’re safe in here, the air burns them

. But his throat was so tight with horror he could barely breathe. Jhutti pressed the button, and the hatch closed.

‘Both dead!’ cried Jhutti. ‘Devoured – both men devoured!’

‘They were tested,’ said Billiard-Fanon, in a strange voice. ‘God tested them, and they were found wanting.’

‘How can you say so?’ demanded Jhutti. ‘How can you possibly say that?’

‘Do not raise your voice at

me

, M’sieur,’ said Billiard-Fanon, placidly. ‘Did I not

also

swim through the shoal of devils, like Daniel in the den, like Shadrach, Mesach and Abednego in the fiery furnace? And I am unharmed! I am unharmed!’

All three men were still inside the tunnel.

‘I need penicillin,’ Lebret gasped. A flush of terrible heat was washing through his body. His eyes were streaming, his muscles twitching and trembling. ‘I fear that I have contracted blood poisoning.’

Billiard-Fanon took Lebret’s face between his two hands and looked into his bleary eyes. ‘I did

not

miss,’ he said. ‘I took aim at your face, right in the middle of your face, and I fired. Yet God has spared you!’

‘I need first aid,’ said Lebret. Helplessness almost overwhelmed him; tears of frustration and pain filled his eyes. As he blinked them away they had the effect of making Billiard-Fanon seem to shimmer and twitch, as if possessed by devils. ‘I am dying,’ he gasped. ‘But penicillin will save me—’

‘God spared you!’ Billiard-Fanon cried. ‘

He

has a plan for you, my friend. Can you not see his light, glinting in my eyes?’

Lebret could see very little now. He was wheezing heavily, his whole body in a feverish agony. ‘Penicillin,’ he croaked.

‘You

have no need

of medicine!’ Billiard-Fanon declared, letting go of his face. ‘God has spared you! He will not let you die. You were a wicked man, I know; a traitor and murderer. But God’s grace is available even to the most wicked! If you have repented, in your heart. If you accept Christ. Your faith will cure you.’

Lebret did not have the energy to argue. He was aware of his surroundings only through a veil of pain and fever.

Jhutti carried him down the corridor and into the main chamber; and he heard Billiard-Fanon crying out about devils and monsters and instructed Satan to get behind him – which must have meant he had laid eyes upon Dakkar. Then Lebret slipped into a dream of being flayed, or of sinking into a bath of acid, or some nebulous but horrible Boschian experience of that nature.