Two Rings (26 page)

Authors: Millie Werber

We picked ourselves up and walked the rest of the way, grabbing on to the tree trunks and branches for support as we made our way down.

The cottage was old and shabby. We knocked quietly on the thin wooden door, not wanting to wake everyone inside.

An old man answered, thin and stooped; we could see just past him into the one small room: A cow stood idly in the middle. The man had no barn for his animal, so it lived with him. We knew this man couldn't have much, but we were fairly desperate. We hadn't eaten in two days; we had been sucking on bits of ice. I took off my ring, the little band Jack had given to me just a few days earlier in Livorno, and held it out to him. We had nothing else to offer, and we needed, desperately, to eat. But the man wouldn't take it. He told us, in German, that we were now in Austriaâwe had managed to cross the border without knowing itâbut that he had nothing he could give us; he could barely feed his own family with the meager amount he had.

An old man answered, thin and stooped; we could see just past him into the one small room: A cow stood idly in the middle. The man had no barn for his animal, so it lived with him. We knew this man couldn't have much, but we were fairly desperate. We hadn't eaten in two days; we had been sucking on bits of ice. I took off my ring, the little band Jack had given to me just a few days earlier in Livorno, and held it out to him. We had nothing else to offer, and we needed, desperately, to eat. But the man wouldn't take it. He told us, in German, that we were now in Austriaâwe had managed to cross the border without knowing itâbut that he had nothing he could give us; he could barely feed his own family with the meager amount he had.

He wished us luck and sent us on our way.

It was full daylight by this time, and we were worried that we might be taken for smugglers in this border town. We must have looked a mess after our night on the mountain. We fell in with a group of workers and tried to walk along with them so we would not be noticed. I walked behind Jack, keeping my eyes down, wanting, as ever, to be unseen. But I saw. Looking down, I saw that Jack's pants, flimsy city things unfit for the mountains, had been torn to shreds on the ice, and as they tore, his skin tore, too, and now the shreds of fabric and skin had frozen together. His backside was frozenâthreads and flesh and bloodâfrozen into one. He must have been too cold, perhaps too scared, to feel the pain. I knew we had to get inside somewhere; he had to warm his body. What would happen if he got frostbite on his backside?

We passed a store; maybe it was a bakery, I don't know. I remember there were round ovens inside. We went in and

showed the woman there what had happened to Jackâhe just turned around and I pointed to his backside. She let us warm up by the ovens, and she gave me a needle and thread to try to sew up Jack's pants after they had softened and I was able delicately to separate the fabric from his skin. It wasn't very good; the pants really needed a big patch, but we managed. As always, we managed.

showed the woman there what had happened to Jackâhe just turned around and I pointed to his backside. She let us warm up by the ovens, and she gave me a needle and thread to try to sew up Jack's pants after they had softened and I was able delicately to separate the fabric from his skin. It wasn't very good; the pants really needed a big patch, but we managed. As always, we managed.

We found our way to the train station and headed, without eventâthank Godâback to Germany.

Â

Â

Â

In later years, Jack and I would marvel at what we went through on our little adventure in Italy. How stupid we were to try to cross the Alps on our ownâtwo city-dwellers tackling a mountain. It's absurd, if you think about it even for a moment. We could have died out there on the mountains, and no one would ever have known. But somehow, by luck, by chance, by nothing more solid than thatâsomehow we made it, and when we arrived back in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, we made our arrangements to get married.

15

JACK WAS A ROMANTIC. FROM THE VERY BEGINNING UNTIL the very end, he always wanted to sweep me off my feet, to celebrate my presence in his life. We were married on January 24, 1946. We had no money, no photographer, few guests. The war was still raw for all of us, and we were all as much aware of the many, many people who weren't with us as we were of those few people who were. Weddings in those days weren't simply joyous affairs. But Jack worked hard to make the day grand, and I loved him for the ardor of his effort.

I was finally reunited with my father when Jack and I returned to Garmisch-Partenkirchen. My father agreed, heartily, to the marriage: Jack was known to be a good man, and he came from a good family. Feter gladly endorsed the idea, too. Feter's approval mattered a lot to me; during the war, he had saved my life. Twice, reallyâfirst, when he had forced me, against my will, to go to the factory to work, and then again when he figured out where to hide me during the oblava in the factory kitchen. He had protected me during the war; his opinion of what I should do afterward meant a lot to me.

Â

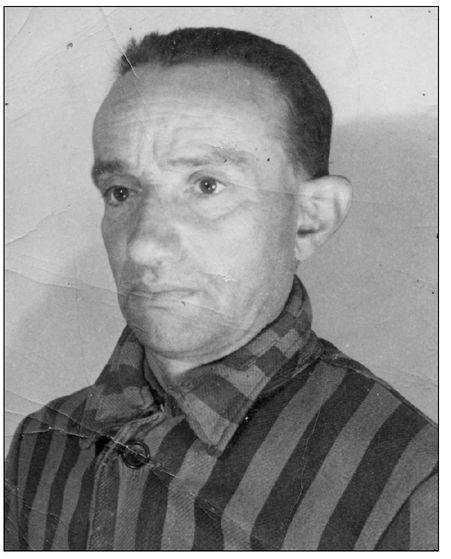

My father, several months after the war

I went to the rabbi in town to ask him to perform the

chuppah

. I didn't mind so much one way or the other whether a

rabbi would officiate at the wedding; I was done with all that, and had been since Auschwitz. I went to the rabbi out of respect for my father and uncle; I knew they would care, and I wanted to please them. But I suppose there are timesânot many, perhaps, but a few over the course of my lifeâwhen my own sense of what is right has outweighed my tendency to conform to other people's pleasures. This was one of those times.

chuppah

. I didn't mind so much one way or the other whether a

rabbi would officiate at the wedding; I was done with all that, and had been since Auschwitz. I went to the rabbi out of respect for my father and uncle; I knew they would care, and I wanted to please them. But I suppose there are timesânot many, perhaps, but a few over the course of my lifeâwhen my own sense of what is right has outweighed my tendency to conform to other people's pleasures. This was one of those times.

The rabbi was an elderly man with watery eyes and vague wisps of a beard. He looked every inch the part, and he spoke to me with a distant formality as we sat across from each other at a table in the apartment where he lived. There was simply no softness in the man. Perhaps he had seen too much during the war; perhaps he had been through too much himself. I know he, too, had survived the camps. What was left of himâif there ever had been any moreâwas hardened, as unfeeling as stone. He agreed to officiate at the wedding, but told me that first I had to go to the

mikveh

, to be ritually purified, according to tradition.

mikveh

, to be ritually purified, according to tradition.

This struck me as outrageous. Purified? Me? In what way, precisely, had I been sullied? I asked him, “Rabbi, do you know where I have been? I have just come from Auschwitz, and you want me to go to the mikveh?”

He didn't care. What mattered to him were only the exacting details of the law. He insisted: Either I go to the mikveh, or he would refuse to perform the wedding.

“Would you prefer that I live with a man without a chuppah? Is that better?” I asked.

I thought perhaps he might try to convince me, might try to explain to me the importance of going to the mikveh. Maybe

he understood the meaning of this ritual; he was a rabbi, after all. Maybe he understood what made it necessary for me to be “purified” before I was wed.

he understood the meaning of this ritual; he was a rabbi, after all. Maybe he understood what made it necessary for me to be “purified” before I was wed.

But he wasn't interested in conversation or explanation. He nearly spat at me: “I don't care what you do: Either you go to the mikveh, or I won't perform the chuppah.”

So I shot back, suddenly, uncharacteristically, defiant: “Then you are not the rabbi for me.” I got up, turned around, and walked out.

I was so proud of that! It felt so good. Even now, when I think about it, I am proud that I had the courage to stand up to that man. For years already, people had been telling me what to do. They said, “Go,” I went; they said, “Work,” I worked. “Get up”; “Lie down”; “Stand here”; “Go there.” That was my life; I had been formed within the pattern of being obedient to orders. But when I went to this rabbi, hardened and hard-hearted as he was, something in me suddenly stood up to protest. His unconsidered command hit up against something solid in me, something strong and unbending, something that said, simply, “No. I won't do this. It makes no sense.” It was my small bid to right an infinitely skewed world. And it felt good.

Jack didn't mind; maybe he was even a little bit proud of me, too. Instead, my uncle would perform the wedding. He had married me to Heniek in the ghetto; he would marry me to Jack, now.

Jack made all the arrangements, such as they were. He had been buying whiskey in Stuttgart, where it was cheaper, and selling it in Lippstadt for a small profit, so he had accumulated

a little money. He bought burgundy-colored material, which we had made into a wedding dress. The dressmaker asked to be paid in food, so Jack asked Srulik Rosensweig, the man who worked in the American kitchen and would bring cans of soup for us back to the apartment, to take something from the kitchen to pay the dressmaker, and he did. Jack wanted me to have my hair done, like a proper, elegant lady. So he found a hairdresser and went out and scavenged some wood so she could build a fire to heat the water she washed my hair with. He asked my father to go to Feldafing, a deportation camp not far from Munich, to see if he could find some kosher meat to serve at our little wedding party. We were living like vagabonds with nearly nothing to our names, managing from day to day on leftovers, scraps, whatever bits and pieces we could findâa sandwich made from the fat off the top of a can of soup; a dress stitched together from a soldier's discarded uniform. And yet Jack took these bits and pieces and out of them created a miracle of a day, a wonder of a wedding.

a little money. He bought burgundy-colored material, which we had made into a wedding dress. The dressmaker asked to be paid in food, so Jack asked Srulik Rosensweig, the man who worked in the American kitchen and would bring cans of soup for us back to the apartment, to take something from the kitchen to pay the dressmaker, and he did. Jack wanted me to have my hair done, like a proper, elegant lady. So he found a hairdresser and went out and scavenged some wood so she could build a fire to heat the water she washed my hair with. He asked my father to go to Feldafing, a deportation camp not far from Munich, to see if he could find some kosher meat to serve at our little wedding party. We were living like vagabonds with nearly nothing to our names, managing from day to day on leftovers, scraps, whatever bits and pieces we could findâa sandwich made from the fat off the top of a can of soup; a dress stitched together from a soldier's discarded uniform. And yet Jack took these bits and pieces and out of them created a miracle of a day, a wonder of a wedding.

He gave me chrysanthemums. A cold-weather flower, a flower needing long nights to bloom, a flower befitting our experience. But these chrysanthemums were white and lush and thick with life, befitting the day.

Jack took me to the attic of the apartmentâhe always thought attics held a special romance; he offered me the flowers, and he gave me a scrap of paper torn from a brown bag on which he had written a wedding poem:

White flowers, tender flowers

Like your soul free from sin

Despite the difficult, hard life

Not altered by storm, cold and wind.

Like your soul free from sin

Despite the difficult, hard life

Not altered by storm, cold and wind.

Â

The tender flowers I send to you today

May they continue to be your symbol;

From the depth of my heart

My wish beams with love and much joy

I should be your last one and you my last one,

Always mine.

May they continue to be your symbol;

From the depth of my heart

My wish beams with love and much joy

I should be your last one and you my last one,

Always mine.

In the middle of winter, a flowering poem, a poem like a flower that grows white, despite its sojourn in the dark.

After all that Jack had endured, where did he find the resources to write something of such delicate beauty? This was astonishing to me. And, too, the hopeful confidence about the future without pretending to eclipse the pastâthat we were not for each other the first, but, oh, that we might be for each other the last. I treasure this poem, its beauty, its honesty, its love.

I read the poem with Jack looking on. When I was done and looked up at him, overcome, I think, by the simple beauty of the thing in my hands, Jack took me in his arms and bent his head to mine, and he kissed me then with a passion, an urgency even, I had not known he owned. And I was surprised to find and pleasedârelieved, to be trueâthat I wanted him just as much. I wanted him, too.

Â

Â

Â

We went first to a German justice of the peace for a civil ceremony. Jack joked, “I'm taking you to a priest to get married.” It was, I have to say, somewhat mortifying to stand before a German official and listen to him pronounce us man and wife. What had the man been doing a year earlier? Where had he been? But never mind. It was a bright winter day, and we rode to City Hall in an open sleigh drawn by a white horse. It was something out of a fairy taleâme in my new wedding dress holding my oh-so-white flowers and the snow glistening all around. It was beautiful, and it was fresh and clean and crisply bright.

My uncle performed the chuppah at the apartment. Other than the two of us, my father, Mima, and Feterâwe had maybe twelve other people with us, all from Radom. The ceremony was performed according to tradition; the celebration

after, with meat supplied by my father, was simple and brief. A friend of ours somehow managed to scrounge two oranges for the occasionâa rare delicacy even before the war. Those oranges provided what luxury the wedding had, and we were grateful to see them set on our wedding table.

after, with meat supplied by my father, was simple and brief. A friend of ours somehow managed to scrounge two oranges for the occasionâa rare delicacy even before the war. Those oranges provided what luxury the wedding had, and we were grateful to see them set on our wedding table.

It wasn't much, but it was enough. Jack and I had found each other. We were in love. We were married. That was a start. That was enough.

Â

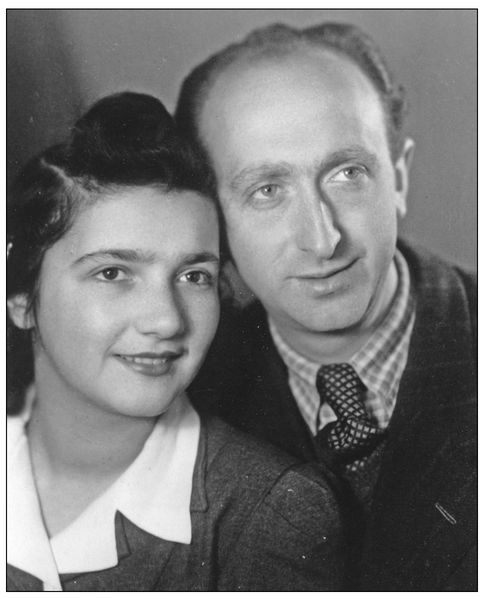

Jack and me, 1946

Other books

LLOYD, PAUL R. by Hags

El dragón de hielo by George R. R. Martin

The Reign of Wizardry by Jack Williamson

The Great Pony Hassle by Nancy Springer

The Trinity: The Ashland Pack Series by Bryce Evans

Destiny Abounds (Starlight Saga Book 1) by Annathesa Nikola Darksbane, Shei Darksbane

Whipped) by Karpov Kinrade

Long Mile Home: Boston Under Attack, the City's Courageous Recovery, and the Epic Hunt for Justice by Helman, Scott, Russell, Jenna

Hasty Tasty Low Carb Snacks & Appetizers by Claudia Jayson

Complete Works of James Joyce by Unknown