Two Rings (27 page)

Authors: Millie Werber

16

JACK HAD NEVER MET HIS BROTHER MANNES, AND I COULD tell that my husband was both eager and anxious when we arrived at the door of Mannes's handsome Victorian home in Beacon, New York. It was the end of June 1946; we had been met at the boat by Jack's uncle Philip, and he had brought us up the Hudson Valley that first evening to stay with Mannes, who had guaranteed our passage. The door opened on an elegant entryway, and we saw Jack's brother and his wife standing in the gentle light. Mannes stepped forward at once, greeting us warmly, enfolding us both in an oversized embrace.

Mannes's wife, Brina, on the other hand, was another story entirely. She stood stiffly beside him, arms folded across her ample chest. We were ushered into the front hall; she said a formal hello to Jack, and then, glancing briefly up and down the length of me, she asked Jack, “This is your wife?” She didn't address me; she didn't extend a hand; she barely nodded

in my direction. As if I were some appendage, like a piece of old luggage Jack had brought along.

in my direction. As if I were some appendage, like a piece of old luggage Jack had brought along.

Then, to me, for the first time: “You should take a bath.” Not “Please come in. You must be tired from your trip. Would you like to sit down?” Not “Would you like something to drink?” Not “Welcome to my home. Thank God you have survived and made it to America.” Not anything warm, not anything human. Just “Take a bath,” as if before she could touch me, before she could sanction my body on her bedsheets, she needed first to ensure that I washed the European germs off me.

Okay, I thought, okay. Maybe I'm being a little sensitive; maybe I'm mishearing the iciness, the cold condescension in her voice. She was, after all, a rich and well-established woman. Her husband had invented the design for one-piece pilot uniforms. Like the children's snowsuits you see now, where a single zipper extends from one shoulder all the way across the body and down the opposite leg, the design had allowed airmen to get into and out of their uniforms with ease. Mannes had gotten multiple military contracts during the war and had grown rich. Brina was from Radom, just like the rest of us, but she was a big shot in America now, and here I was, fresh from an overseas voyage out of an old and old-fashioned world. She probably saw me gaping at the Studebaker in the driveway as I came in; who had ever seen anything like that before? Maybe what I heard as dismissive disdain was just a newfangled form of formality.

I took my few things and went upstairs. As I undressed in the attic bedroom where we would sleep, I heard the tub being filled on the second floor, which surprised me, because I

thought I would be expected to draw my own bath, especially given the way I had been treated when I first arrived. I went down to the bathroom and slipped into the warmth of the tub. That was good. It was good to let myself relax, to settle down into the suds. I was newly pregnant by this time and had just spent ten days on rocky seas lying nauseous on a bunk in the lower deck of an army transport boat.

thought I would be expected to draw my own bath, especially given the way I had been treated when I first arrived. I went down to the bathroom and slipped into the warmth of the tub. That was good. It was good to let myself relax, to settle down into the suds. I was newly pregnant by this time and had just spent ten days on rocky seas lying nauseous on a bunk in the lower deck of an army transport boat.

Someone knocked at the door. “Don't wash your face.” It was Mannes. I couldn't understand why he would say that, but I didn't pay it much attention. A few minutes later, he knocked again. And again came the obscure instruction through the door: “Malka”âhe called me by my Yiddish nameâ“don't wash your face with the bathwater.” This got me nervous, wondering what was wrong with the water that I shouldn't let it touch my face. Then a third time: “Don't wash your face, Malka. We put a disinfectant in the water.”

It was like the earth had opened underneath me. I was back in Auschwitz, being deloused. I had thought that, finally, I had arrived in a place of safety, a place where I wouldn't have to feel myself always the outsider, the unwanted, the scum of the earth. I had thought that maybe here, in this new land of opportunity, Jack and I could start again from scratch, start clean and build something together, a new life. But I was made to realize that here it was no different; here, even in my own family, I was still the dirty Jew.

Â

Â

Â

I hadn't wanted to come to America. Even though Jack wanted very much to meet his one remaining sibling, I kept thinking of what my grandfather said to me when I was a childâthat the streets in America were made from traif. Even with all the optimism people had after the war for the endless opportunities of Americaâin America you could be anything, in America people could grow richâstill, America seemed frighteningly foreign to me, utterly unlike anything I understood as home. But I knew that I didn't have a home in Europe anymore. A couple Jack knew had returned to Radom some months after the war, and they had been hanged by the local Poles, who presumably feared that the couple might want their property back. So Jack worked with the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, the Jewish agency in Europe, to arrange for our passage, and we set off, along with my father and Jack's one remaining nephew, Sidney, in the middle of June 1946.

Â

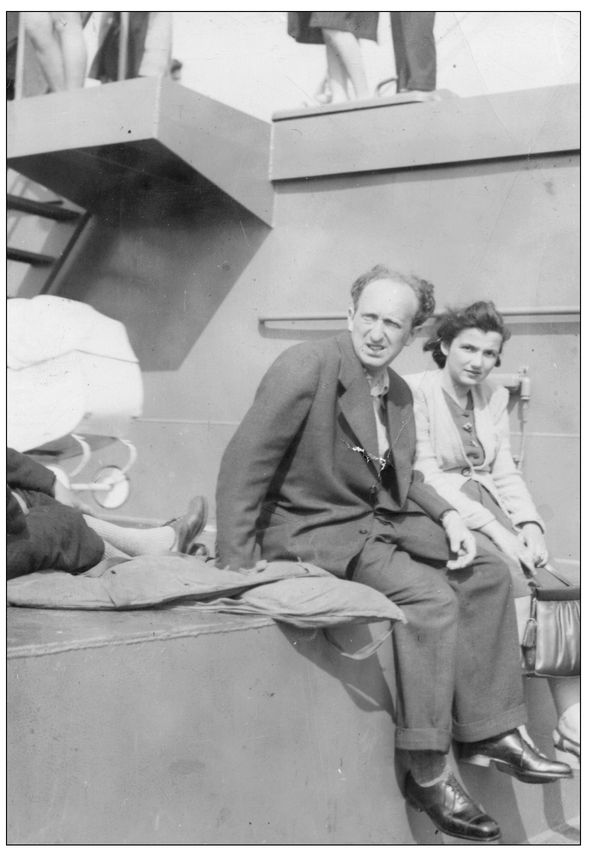

On the boat to America

It had started out well enough. We recognized Jack's uncle, Philip, at the docks because he was carrying a sign that said “Werber” on it, and we pushed our way through the throng to get to him. Philip took us first to his apartment in the Bronx. He told us he was a roofer and showed us all the roofs along the Grand Concourse that he had worked on. The Grand Concourse in those days was a fancy area; the men dressed in fur collars and the women wore sheer stockings made of nylon. We thought he must be a millionaire to have made all those roofs, but as it turned out, he only fixed roofs; he didn't lay them from scratch. Still, his apartment building was on a lovely, tree-lined street, and as we entered his apartment, we saw a tremendous table that seemed to stretch the length of the entire living room. It was piled with food. We couldn't believe how much foodâroasted chicken, sliced brisket, potatoes steaming hot in a porcelain bowl. We had never eaten such a feast. We thought, this is what America

is, this profusion, this easy availability of luxury. Jack's uncle, a simple roof-fixer from Poland, had his own apartment and didn't want for food; he even owned a car. It felt good to get to this America. This land of possibility, we thought, might hold possibility for us, too.

is, this profusion, this easy availability of luxury. Jack's uncle, a simple roof-fixer from Poland, had his own apartment and didn't want for food; he even owned a car. It felt good to get to this America. This land of possibility, we thought, might hold possibility for us, too.

That seemed less trueâor not even true at allâonce we arrived at Mannes's house. For the three weeks we spent there, we were made to feel that we were nothing at all.

Â

Â

Â

I had brought with me from Europe a bar of soap, a little oval of Palmolive soap that smelled like a field of fresh-cut flowers. Mima had found it somewhere when we were living in Kaunitz. This bar of soap, neatly wrapped in its corrugated green paper, was for me a token of another world, long before the war, a world where women had soft skin and silken hair, a world in which women could walk down the street and smell fresh and cleanâlike the women from the magazines my mother used to keep in our apartment for her clients to look at. I loved this little bar of soap, and I decided right away when Mima gave it to me that I would never use it; I didn't want to use it up with water and washing. I made myself a little promise insteadâthat whenever I would be able to buy real underwear, whenever I could get some panties and bras and stockings of my own, I would nestle this sweet-smelling bar of soap among my delicate underthings, and I would be able to wear that lovely scent upon me every day.

And that's what I did. I kept the soap as a sachet, and when I arrived in Beacon fourteen months later, I still had that bar of soap with me.

After ten or twelve days on the boat, and now in Beacon for several more, I wanted to do some clothes washing, so I asked Brina if there was someplace I could wash out a few of our clothes. Yes, she said, in the basement; I could find a basin and a slop sink there, but she didn't have any soap. “Oh, I have some soap,” I told her. “I'll give you mine.” Though I thought it was odd that she didn't have any soap for her own washing, I went and got my bar of Palmolive, and Brina took it from me and ripped off the paper wrapping, and, handing it back to me, said, “Good, you can use this.”

So I washed out our clothes in the basement slop sink, and I used up my little bar of soap. I gently cried the whole time as I watched it dissolve.

When Mannes saw me later that day, he could tell that I had been crying, even though I tried to hide it. He asked what was wrong. I told him I was fine, that I had just been doing some washing during the afternoon and I was tired. He asked if I liked the washing machine they had. Washing machine? What washing machine? I did everything by hand. “Why did you do that, Malka? We have a beautiful machine that will do the washing for you.” And he showed me the thing in the basement, and he pointed out the box of soap powder on the shelf right above it. It was Ivory soap. I didn't know the name, and I couldn't read the English writing on the box.

Why was Brina so harsh? She didn't know me; she didn't know Jack. What could she possibly have had against us that she treated me with such contempt?

Perhaps I was an embarrassment to her; perhaps she thought of me as the immigrant Polish servant girl. I was prost,

common, like Chava, Chiel Friedman's wife. Brina treated me as the ignorant laborer, alive only to do her bidding.

common, like Chava, Chiel Friedman's wife. Brina treated me as the ignorant laborer, alive only to do her bidding.

Mannes suggested that Brina take me shopping. I had been wearing a suit I had made in Europe using material from a suit that belonged to a man. It had a loose-fitting jacket and a long, wide skirt. It wasn't much, but I thought it was pretty enough. Apparently, though, it wasn't the style in America. I came down one morning from the room Jack and I shared in the attic, and Brina looked at me and said, “Look what she is wearing!” As in “How pathetic! How scandalous that she should be dressed this way.” The current style, it turned out, was just the opposite of what I had onâpencil skirts, everything tight to the body and trim. I was out of fashion. This was apparently intolerable. Kindly Mannes suggested a correction.

Brina and I set out for a day in town. I was nervous to go out with her; I didn't know what to expect. I was thoroughly in her power; I didn't know my way about the town, and I didn't yet know any English. But, still, I was excited by the prospectâthe idea of going into a store, with money to spend; the idea of looking around at the items for sale; to pick up, maybe, a hat, a pair of gloves; to try something on and look at myself in the mirror. These simple pleasures in life, these girlish delightsâthey had been lost to me for so long. I was happy at the idea of a little adventure.

We went first to a shoe and hosiery shop. Brina was known there, as she was known throughout Beacon. The proprietor greeted her warmly, and Brina introduced me as if I were a charity case, a pathetic creature from another world: I was her “greener.” That became Brina's standard descriptor of both me and Jackâher “greeners,” her greenhorns. The term had such

condescension in it; it was so breezily dismissive, so cavalier: a greenhornâsomeone ignorant, someone foreign, maybe not quite human. The wordâit's the same in Yiddish as in Englishâcomes from the Middle Ages; it refers to a young cow whose undeveloped horns are still green.

condescension in it; it was so breezily dismissive, so cavalier: a greenhornâsomeone ignorant, someone foreign, maybe not quite human. The wordâit's the same in Yiddish as in Englishâcomes from the Middle Ages; it refers to a young cow whose undeveloped horns are still green.

The store owner looked at me with a mixture of pity and dismay. I felt awkward and embarrassed, but I was angered, too, that Brina had presented me as if I were a pauper. The man must have understood Brina's meaning, because he went to the back and got several pairs of stockings to give meâfor free, as a form of charity. It was generous of him, to be sure; but I was mortified. I had no wish to be a charity case.

He handed me the package, I nodded my thanks, and we left.

Woolworth's was next, the local five-and-dime. I remember feeling overwhelmed by the amount of stuff they had for saleâaisle after aisle of household goods, stationery, toiletriesâeven an aisle for “Sundries,” for items that didn't fit into any other category. Brina bought some things and handed me the bag to carry for her on our walk home.

It's not that I minded the carrying so much; I would have been happy to carry a package for her if she had asked. But she didn't ask; she presumedâas if the whole reason for my being there, for being out with her shopping was

so that

I could carry the packages for her.

so that

I could carry the packages for her.

When we got home, she took the bags from meâboth the one from the hosiery shop and the one from Woolworth'sâand she kept the contents, stockings and all, for herself.

I began to realize that I was her maid. I had come to America to be Brina's maid.

One afternoon, I sat outside to take a little rest in the sun. Brina called to me from the kitchen: “Malka, come here.” Dutifully, I came in and saw her sitting at the table grinding meat. She said, “Malka, here: grind this meat for me.” No need for pleasantries, no need for warmth, no need to ask, might I please. . . . I was her servant, not a guest, not a member of her family.

I grew frightened of her.

Other books

The Apothecary by Maile Meloy

Blaze by Andrew Thorp King

The Unofficial Downton Abbey Cookbook by Emily Ansara Baines

Strike Out Where Not Applicable by Nicolas Freeling

The Wedding Affair (The Affair Series Book 2) by Suzanne Halliday

Secret Father by James Carroll

Creekers by Lee, Edward

The Book of Someday by Dianne Dixon

Hearts in Darkness by Laura Kaye

Faithful Ruslan by Georgi Vladimov