Read Two Souls Indivisible Online

Authors: James S. Hirsch

Two Souls Indivisible (15 page)

"Have you seen them?" Cherry asked.

"Seen who?" Halyburton said.

"The little men."

"What little men?"

"The little air-conditioning men. They keep me cool inside."

Halyburton tried to lift his cast up.

"Maybe they went for more fuel," Cherry said.

"Fuel?"

"They keep me cool. I hope the guards don't catch them."

"How do these men get in here?"

"They come in under the door. They work on my air-conditioning unit."

"You're right then," Halyburton said. "They probably went for more fuel."

His words of comfort would stay with Cherry for years to come. Halyburton could have said there were no little menâor told him that he was crazyâbut he didn't. When Cherry was on the brink, his roommate gave him hope that his air conditioning might be fixed.

It was clear that surviving Vietnamese medical care might be as challenging as surviving the torture. Once, a doctor came to the cell to give Cherry a shot, bringing along a burner so he could sterilize the needle in boiling water. He pulled it out with forceps, dropped it on the groundâthen attached it to the syringe.

"You need to put the needle back in the water!" Halyburton yelled.

"No, no, no," said the doctor, waving him off.

Halyburton kept demanding to see the medic, warning the guards that Cherry was going to die. He got no response. Then, on March 12, more than a month after the cast had been put on, the guards moved Halyburton and Cherry to another section of the Zoo, a building called the Garage. There was no explanation for the move. The new cell was larger but darker, mustier, and less comfortable. Their bed boards were on sawhorses.

Cherry, semiconscious, knew he was near death, but when he was lucid he always had the same thought: I will not die in this prison, I will not die in this prison. He had fought too hard all his life to die in this prison. He also realized how much he depended on Halyburton, how he couldn't survive without him. He never wanted to leave him.

On March 18, the medic came to the cell and had Cherry taken out on a stretcher; his belongings remained. He and Halyburton believed he'd be coming back, but when the other prisoners saw him leave, word spread through the camp: Cherry had been taken away to die. Actually, he was returned to the hospital, once again for a short visit. As the cast was removed with a scissors and a saw, Cherry saw his decaying flesh fall off. His thighs looked the same width as his arms. He figured he weighed about eighty pounds, skin wrapped in bone. He also had lagoons of pus on his body and at least a half-dozen bedsores. Then someone picked up a green beer bottle and poured it over his torso. The bottle contained not beer but gasoline, which burned like fire over his gaping wounds. The fumes overwhelmed him.

The gas was not for tortureâit wasn't the "season" for torture, according to Cherry, and the authorities had more devious instruments at hand. It was considered a healing agent, but its vapor was so strong that it knocked him out. He awoke to the doctor slapping his wrists, leading him to believe that his pulse had stopped. He was then given a blood transfusion and fed intravenously.

Returning to his cell in bandages, Cherry was carried in on a stretcher, which was placed on his bed board. An intravenous tube went into his arm, its bag of fluid held by a stand. His bad shoulder was back in a sling, his fractured wrist still not healed. Halyburton draped the mosquito net over him, exposing only his arm with the IV. Cherry had been gone only a few days, but Halyburton was stunned by his physical deterioration. Asleep, he looked more dead than alive.

The next morning Cherry complained that his shoulders were being crushed. Halyburton discovered that the stretcher was supposed to be elevated by six-inch legs, but the bar to lock the stretcher and keep the patient elevated wasn't working, so its sides were pressing in against the sunken Cherry. He felt as if he was being squeezed to death by his own body. Halyburton piled extra clothes beneath Cherry's shoulders, easing the pressure.

"We're in a helluva mess now, Fred," Halyburton said, a line he'd occasionally use to lighten the mood.

Cherry described the removal of the cast and the gasoline bath. Halyburton just shook his head as he said, "I can't believe they did that."

Though now free of the cast, Cherry was in no better shape. He still couldn't move his arm, and all he had to show from the cast was a body pocked with soresâHalyburton counted nine.

At least he was now receiving antibiotics and was no longer hallucinating, but the IV was no panacea. Unknown to Cherry, in the hospital a small tube had been inserted in his ankle, which could be hooked up to an IV line. Presumably this approach would spare a medic the difficulty of finding a vein in his desiccated arm, making transfusions easier. So the medic came to the cell, disengaged the IV, and inserted the line into the ankle tube. After he left, Cherry looked up at Halyburton and said, "Bubbles are going up my leg."

Halyburton thought it could kill him, so he banged on the door and yelled for an interrogator. Not willing to wait, he pulled the line out of the tube, causing the fluid to pour onto the floor.

The medic came first, and Halyburton, frustrated and angry, pushed him toward the door and demanded to see a doctor or interrogator. A guard retaliated and slammed Halyburton against the wall, but he got what he wanted. Eagle, the camp commander, came to the cell. Halyburton hadn't seen him since Heartbreak.

"There's air in there!" Halyburton said, pointing to the tube. "You're going to kill Cherry!"

According to Eagle, Halyburton should have been grateful that the Vietnamese had saved Cherry at the hospital. "Cherry almost died," he said.

"Yeah, that's what I've been trying to tell you for a long time," Halyburton said.

"Yeah, but you have a very bad attitude. You don't speak to guards and doctor that way."

The following day another doctor came to the cell, cut an incision in Cherry's other ankle, and inserted a tube. This one, however, was never used, and soon both tubes were removed and the ankles bandaged, leaving two scars as permanent reminders of Vietnam's medical care.

The new shoulder bandage created a different problem: it was too tight. "My arm is going to sleep," Cherry said. Halyburton investigated the wrap and decided he could do better. He unwound the bandage and for the first time saw the impact of the cast: two

As an aviation cadet in 1952, Fred Cherry was often the only African American among his peers, but his piloting skills erased conventional prejudices against black fliers. Courtesy of Marion Godwin

The cockpit was Cherry's ultimate refuge, allowing him to fly above the poverty and segregation of his youth. Courtesy of Marion Godwin

Commissioned in 1952 as a second lieutenant, Cherry became a pioneer in the integration of the Air Force. Courtesy of Marion Godwin

During the Korean War, Cherry performed a daring airborne maneuver when he used his wing tip to secure the landing gear of another jet. Courtesy of Marion Godwin

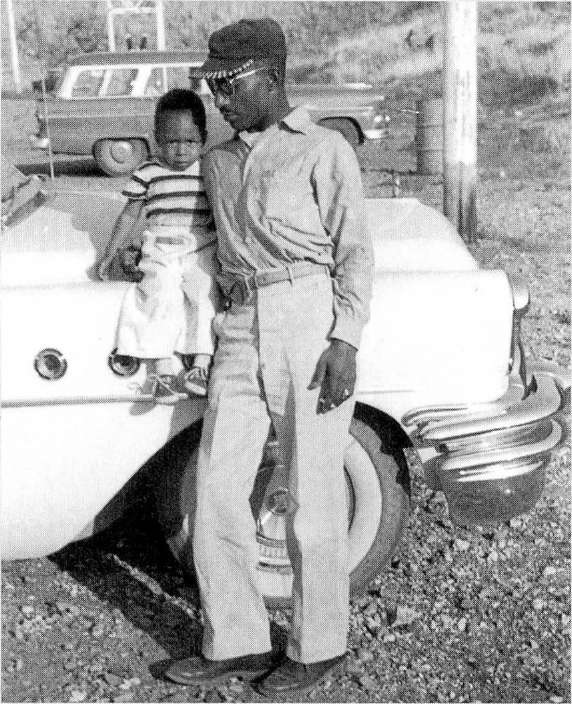

With his adopted son, Donald, in 1955; Cherry was known for his perfectly creased clothes and sense of style. Courtesy of Marion Godwin

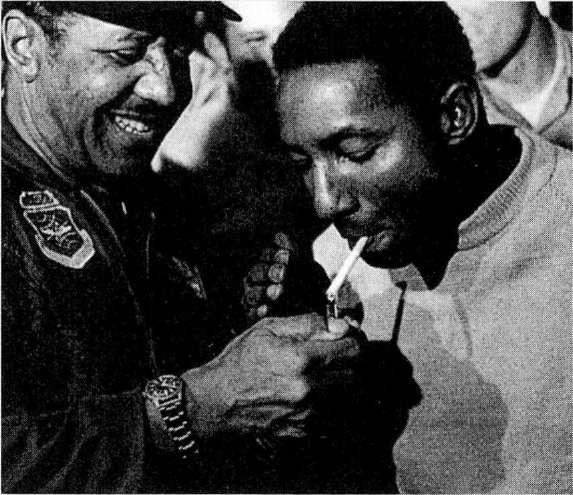

In 1973 Cherry accepted his first light as a free man, at Clark Air Base in the Philippines.

Courtesy of Marion Godwin

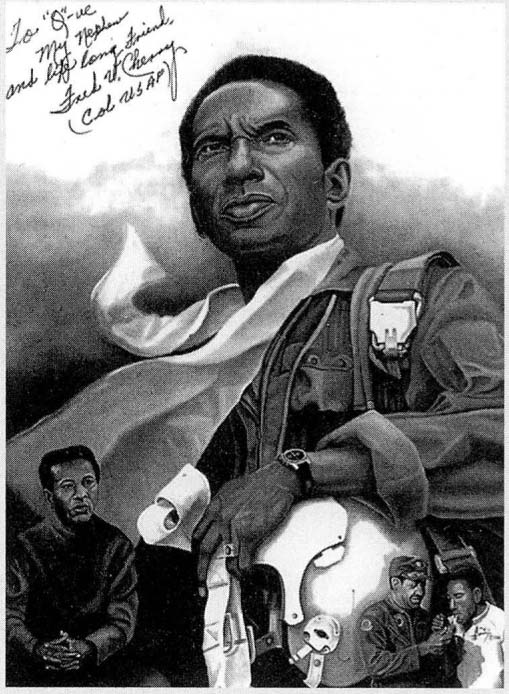

In 1981 the Air Force commissioned this portrait of Cherry, which now hangs in the Pentagon.

Portrait by Harrison Benton