Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (7 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

Earlier that year, Fenway hosted its first NHL game, welcoming the Philadelphia Flyers and Boston Bruins for a regular season New Year’s Day extravaganza. On an unseasonably warm 39-degree day, thirty-eight thousand Boston fans enjoyed a pregame concert by the Dropkick Murphys and then watched the Bruins win 2-1 in overtime.

Kevin:

You weren’t kidding about the Sox diversifying Fenway’s revenue stream.

Josh:

No, I was not.

Kevin:

Concerts. Hockey. Futbol. What’s next, American Revolution re-enactments? Or auto racing?

Josh:

Not funny.

Kevin:

What did I say?

Josh:

You know John Henry owns NASCAR’s Roush Racing team, right?

Kevin:

I do now.

Josh:

He owns the Premier League’s Liverpool Football Club too.

Kevin:

I actually knew that. They’re my favorite football side. Makes me pine for a few pints with the scousers at the Twelfth Man.

Josh:

Huh? What?

Kevin:

You know, the Spirit of Shankly who rock Anfield when Chelsea’s in town.

Josh:

Who? What? Are you talking about Chelsea Clinton or Chelsea Handler?

Kevin:

You really don’t know anything about soccer, do you?

In the middle of the eighth inning Red Sox fans stand in unison and sing along to the 1970s Neil Diamond hit “Sweet Caroline,” shouting out, “So good, so good, so good!” and swaying to the feel-good ditty that blares through the Fenway speakers. And how, you ask, did this unusual ballpark tradition begin? According to a fine bit of investigative reporting the

Boston Globe

did a few years back, it was the brainchild of Amy Tobey, a game-day productions staffer at Fenway who spun the song for the first time at the stadium in 1998 and then periodically afterwards, until 2002 when the Henry group requested she play it during every game.

On Opening Night 2010, Mr. Diamond made a surprise appearance in the Fens in the middle of the eighth. With a microphone in hand, a Red Sox hat on his head, and the words “Keep the Dodgers in Brooklyn” scrawled across his blue blazer, he led the sing-along. Then, the Red Sox finished off a 9-7 win over the Yankees.

Josh:

Keep the Dodgers in Brooklyn? Does this guy know what decade this is?

Kevin:

Maybe not, but I bet he knows why the Liver-pudlians hate Chelsea.

Josh:

Are you talking about Chelsea Handler?

Kevin:

Never mind.

No trip to Fenway would be complete without the obligatory impromptu chorus of “Yankees Suck” during the middle innings. This nightly affirmation of shared purpose and understanding among Red Sox fans is as sure to occur when the Red Sox are playing the Yankees as when they’re playing the Orioles, Royals, Rays, or … well, you get the point.

Look for the K-Men in left-center in Monster Section 10. Whenever a Red Sox pitcher records a strikeout, they post another red K, facing either forward for striking out while swinging or backward for striking out while looking. They also flash signs throughout the game when certain Red Sox players do something notable. For example, they flash A-G-O-N when Adrian Gonzalez hits a homer. This is a tradition that dates back to Roger Clemens’s heyday of the 1980s, although back then the K-Men were in the centerfield bleachers and a metal screen was all that could be found atop the Wall.

The Red Sox play a trio of victory songs over the P.A. system on nights when the home team wins. The eclectic set includes the aforementioned “Tessie,” the uplifting Three Dog Night tune “Joy to the World,” and the anthem “Dirty Water” by the Standells. The water to which the latter song refers is the Charles River, along which the 1960s cult classic informs its listeners they’ll find Boston’s “lovers, muggers, and thieves.” The catchy refrain of “Boston, you’re my home!” sends every Red Sox fan home with an oddly pleasant melody reverberating in their eardrums.

Cyber Super-Fans

- Boston Dirt Dogs

This smart, funny site is the Web’s best source for gossip about the Sox, as well as for trade rumors and conspiracy theories

. - Sons of Sam Horn

This site’s name honors burly Sox flash-in-the-pan Sam Horn, who later served as a studio analyst on NESN for a while

. - The Remy Report

This site comes courtesy of former Sox second baseman/NESN color man/tireless entrepreneur/local restaurateur Jerry Remy

.

As a glam team, the Red Sox have some high-profile fans these days. And we’re not talking about the guys who paint their chests red in the centerfield bleachers. We’re talking about actual celebs who turn out in the Fens to support the home team. Maine author Stephen King is one. He can often be found keeping score in the infield boxes.

Meanwhile, actor Ben Affleck, who has local ties and whose mom still teaches in the Cambridge Public School Department, likes to sit down the third-base line.

Sports in (and around) the City

The Cape Cod League

Barnstable County, Massachusetts

http://v2.capecodbaseball.org/

Each summer the nation’s best college players and a few dozen baseball scouts flock to the peninsula that is one of New England’s premiere vacation destinations. The players, who arrive on “the Cape” to take part in the invitation-only summer circuit, play a forty-four-game schedule that runs from mid-June through mid-August. They live with local families, work part-time jobs, often in support of the Cape’s thriving beach-tourism industry, swim in the warm Cape waters, and bask on the Cape’s beaches. And each night they test their skills against other top prospects. For many players, this is the first time they have to use wooden bats instead of the lighter aluminum ones allowed in the college game. And it shows. Pitchers dominate the Cape League.

In recent decades, the Cape’s ten fields have served as the proving grounds for up-and-comers like Jeff Bagwell, Albert Belle, Will Clark, Nomar Garciaparra, Todd Helton, Ben Sheets, Frank Thomas, Jason Varitek, and Barry Zito. But those are just a handful of the recent success stories. The Cape League actually dates back to 1885. It was a “town league” in those days, and wouldn’t become a college league until 1963. In 1919, though, future Hall of Famer Pie Traynor played for the club in Falmouth. In 1967, Thurman Munson batted .420 for Chatham, a record that would stand until 1976 when Buck Showalter batted .434 for Barnstable.

Today, during a typical Major League season, about two hundred Cape Cod League alumni appear in the bigs, or, to put it another way, one in every seven major leaguers spent a summer on the Cape. And not only do the games on the Cape showcase some of the most highly regarded names on the

Baseball America

top prospects list, but they do so at intimate ballparks that serve as high school fields during the spring. The games begin between 5:00 and 7:00 p.m., and admission is free.

The league’s ten fields are all located within fifty miles of one another. For directions and a current schedule, visit the web address above. Oh, and don’t forget to pack your bathing suit too!

Doug Flutie, the former Boston College and Canadian Football League legend, who finished his career serving as third-string quarterback for the New England Patriots, often sits down the first-base line. He wears a glove on his left hand and once snagged two foul balls in the same game.

Former General Electric CEO Jack Welch is a Sox diehard too. He usually camps out in one of the posh luxury boxes upstairs.

Aerosmith frontman Steven Tyler has been known to sit right behind home plate near Dennis Drinkwater. As for the guy who sits a few seats to the third base side of Drinkwater behind the plate, wearing the oversized 1980s-style yellow earmuff headphones, that’s Red Sox senior baseball advisor Jeremy Kapstein.

We Wrote a Book

During our original trip, we visited most Major League cities for only a few days before piling our junk back into the road trip car and hauling our butts to the next city. And during our second trip, we actually flew around the country in style (read: discount coach seats), watched one or two games in each city, and then headed back to the airport. In both cases, the road or skies always beckoned. But Boston is where it all began. Josh’s home city and Kevin’s onetime adoptive home city served as the launching pad for our adventure.

While we were in Boston, Kevin got married, earned a Master’s degree, and fell in love with New England clam chowder. Josh got married, earned a Master’s degree, and developed a severe food allergy to lobster. Red Sox games were attended. College classes were taken and then, later, taught. Beers and good times were had. But most importantly (with apologies to Meghan and Heather), Boston is where we realized we could parlay our love for baseball and our writing skills into something wonderful. Boston is where

The Ultimate Baseball Road Trip

was born.

Josh had just returned from a brief hardball sojourn during which he and his future wife Heather had visited the ball yards in New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, when Kevin popped his head into Josh’s office at Emerson College where we were both teaching writing courses. Kevin offered his daily “What’s up?”

“Not much,” Josh said.

“Hey, how was the baseball trip?”

“It was …” Josh began, but then he looked away. “It was …” he tried, before pausing and shifting uncomfortably in his seat. Then he lowered his head into his hands and wept like a small child.

“I’ll come back in a little while,” Kevin said, backing out of Josh’s office like a terrified crab. He avoided Josh for the next nine days, before finally stopping in again when he ran out of printer paper. “Recover from the breakdown yet?” he asked, inching his way toward Josh’s supply cabinet.

“Sort of,” Josh said.

“Something terrible happened during the road trip, didn’t it?” Kevin asked.

“Yes,” Josh said.

“Wanna talk about it? What happened? Car crash? Another lobster poisoning? Another incident with Canseco?”

“Well,” Josh said, his eyes starting to well with tears. “It was pretty bad. I ordered a Philly cheese steak at Veteran’s Stadium in Philly and it was … it was … it was … it was bland! And the meat was chewy.”

“You ordered a cheese steak at the Vet?” Kevin howled. “Everyone knows the cheese steaks at the Vet are bland and chewy! Why didn’t you go to

Pat’s

or

Geno’s

?”

“Pat’s? Geno’s?”

“They’re steak joints down on 9th Street. That’s where I get my fix when I’m catching a game in Philly. I could have told you before you left that it was a mistake to get a cheese steak at the Vet!”

“But you didn’t!”

“I didn’t think of it. Don’t feel bad. I ordered a chewy steak myself the first time I went to the Vet. That’s how you learn.”

“So every baseball wanderer that visits Philly has to learn his lesson?”

“At least until the Phillies build a new ballpark … or at least start selling decent steaks inside the Vet.”

“Until then what? Getting one’s hopes up and eating a bland cheese steak at the game is just gonna be part of the visiting fan’s experience?”

“Exactly.”

“That sucks.”

“Yeah, kind of. But it’s not like there’s a baseball bible dedicated to making sure fans get the most out of their ballpark travels … making sure they don’t waste their time and money on inferior cheese steaks or lousy tickets. You live and learn.”

A few days later while sitting in the Cask & Flagon outside Fenway Park, we decided it wasn’t right that baseball fans should travel unaware to foreign big league parks and cities. So we vowed to walk blindly one last time into every Major League park, to take careful notes and occasional pictures, and then to share our tips, opinions, and observations with the world. Our goal was to ensure that no (semiliterate) baseball fan afterward would ever buy chewy meat or substandard seats again. We were fired up and ready to go. Then we procrastinated for three and a half years before getting our act together and hitting the road.

NEW YORK METS,

NEW YORK METS,CITI FIELD

A Diamond Fit (and Priced) for a Queen

F

LUSHING

, N

EW

Y

ORK

10 MILES TO YANKEE STADIUM

105 MILES TO PHILADELPHIA

200 MILES TO BALTIMORE

205 MILES TO BOSTON

C

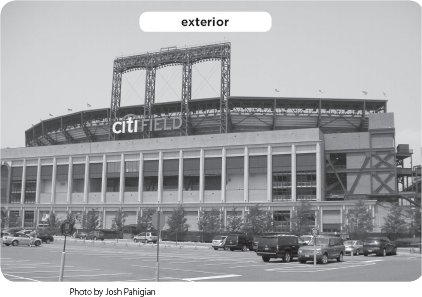

iti Field may not be the coziest ballpark built in recent years. And it doesn’t reside in anything resembling a fun and festive game-day neighborhood. But we’ll give it this: It’s a ballpark, not a stadium like the towering Shea Stadium, which had served as the Mets home from 1964 to 2008. The unfortunate reality for the Mets, though, is that since Citi Field’s opening during the throes of one of the worst US economic downturns in history, it has been widely panned for offering substandard sight lines at exorbitant prices. It certainly didn’t help that the park debuted with the logo of one of the worst culprits of the banking crisis tattooed across its marquee at a time when many American households were still struggling to make ends meet. Citi was one of the largest recipients of TARP, or the Troubled Asset Relief Program, enacted under President George W. Bush. And many people were put off that the banking giant had pocketed $45 billion in taxpayer money, then turned around and paid the most money any company had ever paid to name a sports facility, shelling out $400 million for the naming rights to the new Mets park. But politics aside, Mets fans are still a rabid bunch, and the fact that attendance at their games has fallen from more than forty-five thousand fans per game during the last several seasons at Shea to barely thirty thousand at Citi during 2011, speaks volumes about how New Yorkers have received the new park. It also speaks to the economic reality of the times for fans, as attendance has fallen—though not nearly as dramatically—across MLB.

From the auto-shop-lined streets outside, Citi actually projects a charming old-time façade, even if the towering upper deck rises higher than the regal reddish-brown brick arches that comprise the first few stories. After fans vacate the 7 Train or the spacious parking lots in which they’ve left their road-trip mobiles and walk past the Big Apple that used to periodically emerge from behind the center-field fence at Shea, they pass through the arches and into a beautiful marble rotunda that was designed as a tribute to the entryway of Brooklyn’s old Ebbets Field. In fact, the entire exterior façade, not just the rotunda, was designed to replicate the façade of the ballpark that served the Dodgers from 1913 to 1957. If you Google “Ebbets Field” and refresh your memory of its old façade at the corner of McKeever and Sullivan Place, you’ll see what a striking resemblance Citi bears to it. While this may be a nice tip of the cap to old-time Dodgers fans like Mets owner Fred Wilpon, Citi Field has actually been criticized for this. Many modern-day Mets fans, who grew up going to games at Shea, feel as though the park

goes overboard honoring a history that has little to do with their own.

Similarly, many Mets fans feel that the Jackie Robinson Rotunda is more a Brooklyn Dodgers homage than a New York Mets one. And they’re right. The Rotunda features a big blue No. 42 sculpture, as well as a wealth of Robinson quotes and photos of him with his Dodgers teammates. It does offer entry to an extensive Mets Museum and Hall of Fame that keeps the focus on the home team. But not far away, the Mets Team Store sells not only Mets apparel, but Sandy Koufax jerseys and other pieces of Dodgers gear. And for us, this takes the nostalgia thing a bit too far. While we understand that Mr. Wilpon grew up in Brooklyn and was a childhood friend and teammate of Koufax at Lafayette High School, it struck us as odd to find Dodgers gear on display in the Mets store. We have to agree with the Queens fans that it’s a tad goofy for a team with a five-decade-plus history of its own to hitch its wagon so dramatically to another team’s legacy.

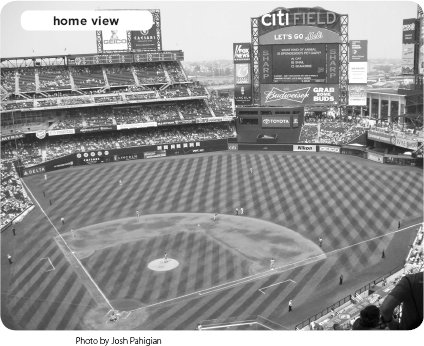

Despite this Dodgers fixation, and the unfortunate fact that 16,400 of Citi Field’s 41,800 seats are on the upper level where we found the views of the field to be pretty poor, we did find many things to like about the park. The open first-level concourse is well done, for example, offering quality views to folks roaming around, except from behind home plate where an in-stadium bar occupies that space. And Citi offers a tremendous range of specialty foods that are available at field level as well as upstairs. At a lot of other parks, the good foods are only sold downstairs. But the Mets made certain to put a top-notch food court on the third level too, and for that we applaud them. We also like the wavy lighting banks high above the upper deck, and the built-in quirks, like the bigger-than-at-Shea Home Run Apple behind the center-field fence, and the distinctive Shea Bridge in right field. Another outfield eccentricity, though, that we were not so keen on: Above the black batter’s backdrop in center, an overabundance of massive advertising signs blocks what might have otherwise been a nice view of Flushing Bay. The video board is dwarfed by the signs surrounding it. Now, we know advertising is part of the ballpark experience these days, just as it was in our fathers’ and grandfathers’ days, but the concept is taken to an absurd extreme when the square footage of the JumboTron pales in comparison to the Budweiser and Geico signs.

Josh:

If I peek between the billboards with my binocs, I can see the bay.

Kevin:

If you have to try that hard, it doesn’t really count as a “view,” does it?

Josh:

At least you can’t see all the chop shops like at Shea.

Citi Field was designed by the noted ballpark architects at Populous (formerly HOK) and built at a cost of $850 million. The funding came from the sale of municipal bonds that will be repaid by the Mets with interest. Construction began in July 2006 in the parking lot behind Shea Stadium’s left-field fence, and was completed in time for Opening Day 2009. Before the Mets took the field for the first time, though, the St. John’s Red Storm hosted the Georgetown Hoyas for a Big East game on March 29, 2009. The visitors won 6-4 after former Mets closer John Franco tossed out the ceremonial first pitch.

Two weeks later, the Mets hosted the San Diego Padres for the first major league game in Citi history and the home fans went home disappointed: The Friars spoiled the debut with a 6-5 win. Jody Gerut actually led off the game for the Padres with a home run. In the long history of big league baseball, that clout ranks as the first and only leadoff dinger to open a new ballpark.

Later that April, aging Met Gary Sheffield hit his five hundredth homer at Citi against his original team, the Brewers. Then in June, the Yankees’ Mariano Rivera notched his five hundredth career save at Citi. The Mets generously awarded him the pitching rubber from the game and installed a new one for the rest of the season.

Another noteworthy event occurred on August 23, 2009, when Phillies second baseman Eric Bruntlett recorded an unassisted triple play off the bat of Jeff Francoeur to end a 9-7 Phillies win. The fifteenth unassisted trifecta in MLB history was just the second to end a game and the first to do so in NL play. Bruntlett caught Francoeur’s line drive, then tagged second base to double off Luis Castillo, and tagged Daniel Murphy as he came trotting in to second.

Josh:

I’ve scored an unassisted Triple Play at Chili’s.

Kevin:

Come again?

Josh:

I can eat an entire Triple Play appetizer and still have room for my meal.

Kevin:

I

thought

you’d expanded a few belt sizes since our first trip.

Although we second the prevailing opinion among Queens fans that the Mets borrowed too heavily from the Dodgers in designing their new park, the team’s reverence for its National League forebears was established long before Fred Wilpon took the reins of the Metropolitans. In fact, the familiar Mets logo fuses Dodger blue and Giant orange. The bridge in the foreground represents the Mets “bridging the gap” that existed after the Dodgers and Giants headed for the West Coast. The skyline in the background depicts buildings from all five boroughs of New York City, including the Williamsburgh Savings Building, the Woolworth Building, the Empire State Building, the United Nations Building, and a church spire symbolic of Brooklyn.

As for the Mets’ longtime home, Shea Stadium was named after prominent New York attorney William Shea, who worked tirelessly to bring Senior Circuit hardball back to the Big Apple after the departure of the Giants and Dodgers in 1958. In 1959, Shea announced his intention to form a third Major League, to be called the Continental League, and to place one of the charter members in New York. A year later, the league disbanded before it played a game, but not before the National League had accepted two of its prospective franchises—Houston and New York—as expansion teams. The expansion of 1962 made the NL a ten-team circuit.

The Mets played their first two seasons at the Giants’ old Polo Grounds, then on April 17, 1964, christened Shea Stadium with two bottles of water—one from the Harlem River that flowed near the Polo Grounds, and the other from the Gowanus Greek Canal, which ran beside Ebbets Field. The Mets lost their first game to the Pirates, then they kept on losing. For the third straight year the Mets finished dead last in the NL, posting 53 wins and 109 losses. Nonetheless, the fans turned out at Shea to watch them play. The Mets outdrew the Yankees, who won the AL pennant that year, selling 1.7 million tickets to the Yanks’ 1.3 million. A full house was on hand to witness Phillies ace Jim Bunning’s perfect game against the Mets on Father’s Day, and then again when Shea hosted the 1964 All-Star Game.

The team’s first winning season came when the “Miracle Mets” of 1969 surpassed the previous franchise record of seventy-three wins en route to a 100–62 mark. After sweeping the Braves in the first National League Championship Series ever played, the Mets downed the Orioles in a five-game World Series.

Kevin:

They’d never finished higher than ninth place in the league before that season.

Josh:

A “miracle,” indeed.

As the first of the so-called cookie-cutter stadiums, Shea utilized motorized underground tracks to convert its stands from baseball to football and vice versa. The horseshoe-shaped facility housed the Jets for two decades and was originally designed to be expandable up to ninety thousand seats, should management ever decide to add outfield seating on all levels.

In the years after Shea’s construction, cities like Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Cincinnati followed New York’s lead and built multipurpose stadiums of their own. While these highly functional and eerily similar-to-one-another facilities efficiently served two professional sports teams in each city—baseball and football—they left fans longing for the day when each ballpark was a world unto itself.

As for those Jets, they set an American Football League attendance record at Shea in 1967, selling out all seven of their games to draw 437,036 fans. But in 1973 the Jets had to play their first six games on the road because the Mets needed Shea for the postseason. Amazingly, manager Yogi Berra’s Mets had won the NL East that year despite having a record of just 83-79. They then dispatched with the Reds in the NLCS before bowing to the A’s in a seven-game World Series. If the Jets felt slighted by being turned out for a stretch, they didn’t show it. They continued to play at Shea for another decade, before finally leaving for the Meadowlands in 1984.