Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (2 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

Josh:

I notice you’re not wearing your Bonds jersey this time ’round.

Kevin:

And you’re not wearing your Clemens jersey.

Josh:

Touché.

Part of the reason it took so darned long for the Steroid Era’s wool to be lifted from casual observers’ eyes was because the sport’s pundits largely protected the modern players from scrutiny. Nearly to a person they’ll profess otherwise, but, as we said, we prefer to tell it like it is. And we are telling you that the game’s most prominent television commentators—most of whom are ex-ballplayers—all had to know something

was amok. During their own playing days, these announcers made it their life’s work to test the very limits of their unenhanced bodies. The years they spend in the booth are meant to allow them to share their wealth of knowledge with their viewers. When players started doing things on the field they themselves had never come close to doing, well, not one came out and said a thing. They had to know. But down to the last man, they remained silent. Are we to believe that none harbored any suspicions about performance-enhancing drugs? We have an easier time believing the Big Tobacco studies expounding the health benefits of smoking.

As far as we’re concerned you can put a black mark next to the name of every scout, general manager, coach, and manager of the era too. They all made a living evaluating talent. Heck, if Josh was onto the juicers—and he was, as a review of the Fenway Park chapter in this book’s original edition demonstrates—they were too. But, lots of fans knew … and were powerless to do a darned thing about it.

You see, back then, there was no way for fans—the one constituency without a vested interest in keeping the game’s big secret hush-hush—to take charge of the conversation. Today, all that has changed. With the rise of the new media, fans play a more active, more direct, and more vital role than ever before in shaping the game’s major and minor story lines. And they do so in real time. Being a fan is a far more interactive experience today than it was a decade ago. That’s why we’ve gone to lengths to make this edition of the book as social-media/cyber-friendly as possible. More than just sharing

our

impressions of the ballparks, teams, and fans across the land, we’ve infused the book with links to the better blogs and Web forums through which each fan base communicates with its members.

In addition, we’ve included links to the ballpark seating maps and ticketing websites, to the menus of sports bars and restaurants, and to a range of other points of baseball interest worthy of cyber (and real world) exploration by readers.

These new aspects of the book are presented, of course, in addition to all of the favorite features of the book fans enjoyed in the first edition. Like its predecessor,

The Ultimate Baseball Road Trip

2.0 is part travel manual, part ballpark atlas, part baseball history book, part baseball trivia challenge, part food critique, part city guide, and part epic narrative. It touches all the bases in endeavoring to make your baseball odysseys fulfilling and meaningful. And it does so within a lively prose style that leaves room for a few dollops of humor and a few dribs and drabs of ketchup (or mustard) along the way. After all, your road trip is important to you. It may just be the most soul-affirming, awe-inspiring, life-altering adventure you ever attempt. In any case, it’s going to be a blast. So, we want your experience reading our book to be fun too.

Everything you need to plan your trip is here. So order those plane or train tickets. Get that tune-up you’ve been putting off. Call your college buddies or dad. Plot your itinerary. Pack your bags. Square things with the boss. Have a heart-to-heart with your significant other, who can either come along for the ride or accept this is something you’ve just got to do. The time is now. One way or another, you’re hitting the road.

The Ultimate Baseball Road Trip

2.0 will be your guide. We’ll be your companions. Just keep us in the glove-box, or on your smartphone, or as a link on the personal computing device of your choice. Whichever, we’ll be there to help you along.

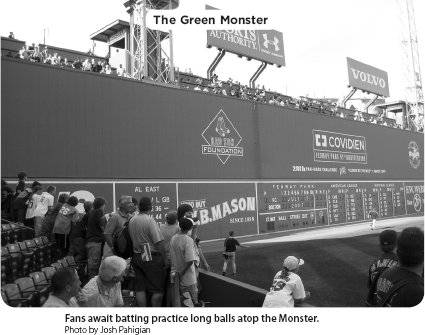

As for our primary piece of advice, it’s to do it all, or to do as much as you physically can. Touch the Green Monster in Boston. Catch a batting practice homer off the B&O Warehouse in Baltimore. Sample the Garlic Fries in San Francisco. Root for the Bratwurst to win the Sausage Race in Milwaukee. Sing “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” three notes off-key in Chicago. Experience all the wonders of the American Game, as you enjoy the most magical summer of your life. Drive safely. Eat heartily. Root for the home team. And keep those e-mails and pictures coming!

BOSTON RED SOX,

BOSTON RED SOX,FENWAY PARK

A Little Green Diamond in the Heart of Beantown

B

OSTON

, M

ASSACHUSETTS

215 MILES TO NEW YORK CITY

310 MILES TO PHILADELPHIA

410 MILES TO BALTIMORE

450 MILES TO WASHINGTON, D.C.

W

ithin Boston’s hardball cathedral, the grass seems greener, the crack of the bat crisper, and the excitement in the air more palpable than anywhere else. In fact, most of the ballparks that have opened in recent years have been designed with Fenway’s old-time charm in mind, as ballpark architects have sought to replicate the nuances of Fenway in much the same way church builders once imitated the Sistine Chapel. “Retro” is the name of the game these days in ballpark design. What’s old is new. Baltimore started the trend when it built Oriole Park at Camden Yards to mimic Fenway’s set-in-the-city ethos, cozy confines, and asymmetrical field dimensions. Cleveland’s Progressive Field offers a nod to Fenway’s trademark thirty-seven-foot-high left-field wall with a nineteen-foot Mini-Monster of its own. Rangers Ballpark in Arlington sports a scoreboard built into the outfield fence like at Fenway. And Washington’s Nationals Park showcases relief pitchers warming up in home-run-territory bullpens that invoke Fenway’s right-field stables.

As the oldest facility in the bigs, Fenway is part ballpark and part time machine. You leave the twenty-first century and enter the 1920s when you ascend the narrow ramps leading from the concourse to the seating bowl and behold the narrow rows of wooden seats, the nooks and crannies created by the zigzagging outfield fence, the slate scoreboard, the green paint, and that looming edifice in left. This living dinosaur has been the stomping grounds of such immortals as Cy Young, Babe Ruth, Jimmie Foxx, Tris Speaker, Ted Williams, and Carl Yastrzemski. It was Boston’s field when your grandfather used to listen to games on a radio the size of a coffee table and when

his

father used to follow the American League the only way a fan could, short of holding a ticket, back then—by reliving the previous day’s events through elaborate newspaper retellings.

Since those dead-ball days, the world has changed to the point where Great Gramps—were he alive today—might barely recognize it, but Fenway has remained essentially the same. Provided you train your eye to ignore the blinking pitch-speed register above the center-field fence, and the neon advertising above the roof in right, your experience within Boston’s ballyard will be pretty close to your granddad’s, right down to the sore butt you’ll drag home after spending nine innings wedged into the tiny hardwood seats that fill the Grandstand. But you won’t mind this slight ass fatigue. Once you’ve gazed at the mighty Monster, rapped your knuckles against Pesky’s Pole, and sat in Teddy Ballgame’s “red seat” during batting practice, you’ll be a convert. You’ll feel like baseball was invented specifically to be played (and watched!) at Fenway. So power down your smart phone, buy a Fenway Frank, and squeeze into that seat.

So where did they come up with the name Fenway Park? No, it wasn’t in tribute to some generous beneficiary named John Q. Fenway. Nor were the rights to the stadium’s name bought and paid for as if the park were nothing but a cheap, tawdry, street-corner … umm … billboard. In fact, when this part of Massachusetts was being developed hundreds of years ago, Boston’s “fens” were a backwater of the Charles River. The Fens Way was the road that ran through the swamp. Thus, the name “Fenway Park.” The Fens were not declared “inhabitable” until 1777, after the completion of a decade-long effort to level the local “tri-mountain” and dump the fill into the 450-acre marsh that became Boston’s Fenway District. Fenway Park was built in 1912 after being designed to fit snugly into the confines of a pre-existing city block. That’s why the field and stands are so irregularly shaped.

After cleaning out their lockers at their old home, the Huntington Avenue Grounds, the Red Sox opened Fenway with a 2-0 win over Harvard University on April 10, 1912. Then, eight days later, the home team defeated the New York Highlanders 7-6 in the park’s first official game. The

opening-week exuberance was dampened, however, by the sinking of the

Titanic

in the icy North Atlantic. Fenway took center stage six months later, though, as the Red Sox celebrated a World Series title on the Fenway lawn after downing the New York Giants 3-2 before seventeen thousand fans in the deciding game. With the victory, Boston’s American Leaguers (who were also known as the Pilgrims, Americans, and Red Stockings in their early days) claimed the second of five World Championship banners they would raise between 1903 and 1918. They might have had six if John McGraw’s Giants hadn’t refused to play the Pilgrims in 1904, owing to the feisty manager’s disdain for the upstart Junior Circuit.

After laying claim to being the most successful franchise of the first two decades of the Modern Era, the Red Sox sold Babe Ruth to the Yankees for $100,000 in 1920. Thus began a long period of what might best be described as haplessness. Following their victory over the Cubs in the 1918 October Classic, the Red Sox would not taste World Series champagne for a very, very long time. In fact, it was eighty-six years before the Red Sox broke the supposed “Curse of the Bambino,” overcoming a three-games-to-none deficit to beat the Yankees in the 2004 American League Championship Series and then sweeping the Cardinals in the World Series. With another Series sweep, this time of the Rockies in 2007, the Red Sox cemented their claim to being the most successful team of the first decade of the new century.

In between these golden eras of Beantown ball the local rooters experienced their share of heartbreak. The Old Towne Team took its World Series opponents the full seven games in 1946, 1967, 1975, and 1986, only to fall short each time. For at least three generations of New England life there were no “Red Sox fans,” only “long-suffering Red Sox fans.” But all that has changed. And as a result, Fenway is a more popular destination than ever before. Game after game, the ballpark sells out, as hardcore fans who have followed the team since birth merge with pink-hat-wearing band-wagon-jumping corporate types. This is an annoyance for Beantown seam-heads, but, most agree, a relatively small tradeoff for the privilege of experiencing what many of their fathers and grandfathers never did: a World Series victory parade.

Kevin:

I miss the curse.

Josh:

Blasphemy! I won’t hear it!

Kevin:

No, I really miss it. It was one of the most mystical things in all of sports.

Fenway has stood the test of time, to be certain, but not without enduring some brushes with mortality. In 1926 a fire destroyed the left-field bleachers and for seven years thereafter ownership cried poverty while third basemen and shortstops tiptoed into the charred rubble after pop-ups. These were dark days for the Boston Nine. Dark and sooty days. Finally, in 1934, the team installed new seats along the left field line. It was at this time that the Green Monster was erected. “The Wall,” as it is known to locals, consists of concrete, and is coated with wood, plated with tin, and covered with green paint. Prior to its construction, a much shorter fence had stood atop “Duffy’s Cliff,” a ten-foot embankment named after Sox left fielder Duffy Lewis, who was adroit at scaling the hill to catch fly balls.

Other changes have been made to the park through the years too. When Fenway was constructed it was customary for relief pitchers to warm up on the field of play behind the outfielders. Mind you, this was during the Dead Ball Era, when long fly balls were rare and starting pitchers usually went the full nine. As time passed, relievers came to more commonly warm up in foul territory or under the stands. Finally, in 1940, the Red Sox brought in the right-field fence and

added twenty-three-foot-deep bullpens in home run territory. It was no coincidence that a sweet-swinging lefty named Ted Williams had burst onto the scene the year before. The pens were dubbed “Williamsburgh” and “The Kid” promptly began dropping homers into the inviting landing strip.

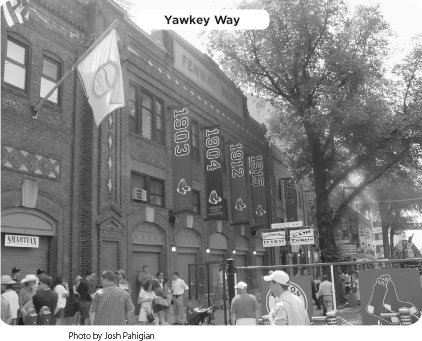

The most obvious modification to Fenway since John Henry’s Fenway Sports Group bought the team in 2002 would have to be the addition of nearly three hundred seats atop the Green Monster. Another biggie was the expansion of the manual scoreboard in left to include the National League scores, which it had decades earlier. Other major changes have included the replacement of the glassed-in .406 Club above home plate with an open-air luxury seating area, the addition of right-field roof seats, the installation of two gigantic high-def video screens above the centerfield bleachers, a massive food court behind the bleachers in right, and the closing of Yawkey Way on game day so that only ticket holders may partake in the just-outside-the-gates festivities. For the most part your humble authors approve of these changes. We understand that Henry and Co. paid $700 million for the team and must cram as many fannies into Fenway as possible. Fortunately, the renovations have been made with the sensibilities of baseball purists in mind and have not too egregiously compromised Fenway’s nostalgic feel. In fact, the Monster Seats are more visually appealing than the ratty old screen into which long fly balls used to settle above the Wall. And they look like they’ve always been there. Likewise, management’s efforts to widen Fenway’s concourses, expand its concession areas, and modernize its facilities have dramatically improved the fan experience. It wasn’t long ago that male fans had to relieve themselves into trough-style urinals that stood in the middle of each Fenway men’s room. We kid you not. And it wasn’t long ago that, in the dying days of the Yawkey Trust’s stewardship of the team, fans and local radio hosts spoke about the replacement of Fenway with a shiny new retractable-roof ballpark on the South Boston waterfront as if it were a not-too-distant inevitability. For preserving Fenway for future generations of New Englanders to call “home,” we tip our caps to John Henry.

Since the arrival of Henry and Co., the Red Sox have added nearly four thousand seats, increasing Fenway’s capacity to a bit over thirty-seven thousand for night games and a bit under that for day games. This unusual day/night split exists because several hundred center-field seats are covered with a black tarp during day games to provide a better backdrop for hitters. Once you factor in the standing room tickets, ballpark capacity settles somewhere around thirty-eight thousand, which gives Fenway one of the smallest “full houses” in the bigs, right there with the Oakland Coliseum, Tropicana Field, and PNC Park. The 38,422 fans the Red Sox drew to a June 2011 game against the Padres was the largest Boston crowd since World War II. That banged-out house also represented the

Red Sox 668th consecutive home sellout. For the record, the biggest Fenway crowd ever to fill the park turned out for a double-header against the Yankees in 1935 to the tune of an official attendance of 47,627. Fans were standing in the aisles, hanging from the rafters, sitting on each other’s laps, and otherwise jamming the park to such a ridiculous extent that soon after, fire laws were put in place disallowing the Red Sox from “over-filling” the park.