Ultramarathon Man (20 page)

Authors: DEAN KARNAZES

We slogged along within eyesight of one another for much of the first half of the marathon. I was pushing as hard as I could to keep up, and it was draining. I would run ahead and stop to change heating pads, and the others would catch upâlike a quasi-hare-and-tortoise routineâand then I'd charge out again, trying to recapture some of the body heat that was lost from the pit stop. A couple of times I asked Doug if the group was sticking close enough to be safely monitored. He reassured me that things were fine. That was comforting, because I was incapable of going much faster.

As the run progressed, my goggles would instantaneously fog whenever I stopped. The cumulative moisture buildup resulted in instant condensation. If I removed my goggles so that I could see, my eyes would start to water profusely and the tears would painfully freeze. So I left the goggles on and fumbled in the haze.

We runners exchanged few words along the wayâprimarily just grumbles about the cold (it was approaching -40 degrees). Talking was difficult with a “gorilla mask” covering your mouth and nose. You had to wear one, though. Breathing the superchilled air directly could freeze your trachea.

By mile 17, icicles had formed under my neoprene face mask, limiting my ability to eat or drinkâor even move my head. My progress in the soft snow was brutally slow as my feet sank deeper into the yielding surface the harder I pushed off. It felt like I was running at full capacity, every muscle in my body working overtime, but with the snow sucking me down I was barely inching forward. By mile 18, I began having serious doubts about whether I could complete the marathon. My heart raced, but I scarcely covered any ground.

I kept going, numbly.

At the 20-mile mark, my fingers were so cold that I couldn't clench my fists. I was unable to change the heating pads in my shoes at this point; I didn't have the dexterity left. The body heat I was generating by running as hard as I could didn't account for much in the sub-zero temperatures. The cold was winning. It seeped in through every seam of my clothing.

When it's cold beyond comprehension, you start losing your natural instincts.

Am I freezing? No, things are fine. Wait a minute, I can't feel my toes! Should I stop?

When the temperatures are so low, just a few minutes of poor judgment can cost body parts. Unlike the heat of Death Valley, where you can seek reprieve in the shade, there was no escape from the polar cold, no place to hide.

Am I freezing? No, things are fine. Wait a minute, I can't feel my toes! Should I stop?

When the temperatures are so low, just a few minutes of poor judgment can cost body parts. Unlike the heat of Death Valley, where you can seek reprieve in the shade, there was no escape from the polar cold, no place to hide.

The altitude was another factor, and one we'd underestimated in our planning. Thinking only of the relative flatness of the polar plateau, we'd failed to prepare for running at the elevation of a significant mountain. I was sucking the frigid, oxygen-poor air at 11,000 feet above sea level through a neoprene muffler that had frozen solid. Every breath was like trying to suck an ice cube through a straw. I was running in the most desolate, open expanse on the planet, suffocating.

What kept me going? Easy. It is what I lived for. The adventure. The challenge of pushing the human body beyond reality. Not only had a marathon to the South Pole never been run before, but plenty of people doubted it could be done, said it would be impossible. I was out to prove that it could be done, regardless of how irrational, how improbable, how dangerous the effort was. That it was obliterating me in the process only heightened my fighting spirit. I had something to prove, if only to myself: that it

could

be done, that nothing was impossible.

could

be done, that nothing was impossible.

At mile 22, my face mask had become a solid block of ice. My breath had dampened it, and it froze stiff. Eating and drinking became impossible; nothing could reach my mouth through the frozen block. But just as worrisome as the inability to eat or drink was the small gap that had developed between my goggles and face mask. The arctic air sneaked through unabated, searing the tissue along my upper left cheek. With the face mask now completely frozen and immovable, it was impossible to seal off the crack. It felt like Novocain was being injected into my cheek. First came the sting of the needle being inserted, then the area tingled and went numb.

This is how people die in the cold. They push too hard and don't realize it until they've gone past the point of no return. The situation had gotten critical. Every step forward came at a mounting price. My muscles were slowly running out of fuel, and there was no way of getting food into my mouth. The vicious air was attacking my face, so I ran with my head hunched over as far as possible in an effort to deflect the biting headwind and prevent further tissue damage. I slogged forward, trying to keep my feet moving through the sinking surface, ignoring the stinging and hoping that I could reach the Pole before having to curl into a ball on the snow.

Periodically, I glanced up in hopes of seeing something. Not only was the horizon difficult to gauge, but my goggles were fogged and frozen, creating a restrictive tunnel vision. I could see nothing but white in every direction.

There was no way to look at my wristwatch without removing a mitten, which was out of the question at this point. Even if I could get to my watch, deciphering the time through these clouded goggles might very well be impossible. We had been out here a long time, that much was certain. Even while I ran at full capacity, the soft snow, which sometimes swallowed an entire foot, bogged me down so badly that it was grueling maintaining a fifteen-minute-mile paceâabout the speed of a brisk walk on a hard surface. I ran as hard as I could, but barely moved forward. Given the stops to change the heating pads in my shoes, I guessed that we'd been going at it for close to eight hours. Usually I could run two marathons in that time, even on the most demanding course. But not here.

My mind was focused on one thing this entire time: getting through the ordeal in one piece. There were no flashbacks or daydreams, no existential thoughts: the intensity of the conditions and the unrelenting physical demands placed upon me commanded all of my attention. And the situation was rapidly becoming perilous.

Doug and Kris were nowhere to be seen. Had their snowmobiles stalled? Were they lost? It was difficult to decipher anything. The snowmobiles would be next to me at points along the way, and then I wouldn't see them for long stretches of time.

If I were to crumple in a heap on the snow, would they ever find me?

One of our guides, Bean, was an experienced back-country pioneer and had instructed us to always save 10 percent of our energy in case something unforeseen occurred. I had long since tapped into that reserve. In fact, I was running on empty by now.

If I were to crumple in a heap on the snow, would they ever find me?

One of our guides, Bean, was an experienced back-country pioneer and had instructed us to always save 10 percent of our energy in case something unforeseen occurred. I had long since tapped into that reserve. In fact, I was running on empty by now.

I kept scanning the horizon, hoping to spot something, anything. Still only white. Then, remarkably, something emerged in the distance. One glance up, there was nothing; the next, there appeared to be something dark on the horizon. Yes, something was out there all right. Elated, I began to sprint. I couldn't imagine it being anything but the Pole; what else could be out here? The quicker I got there, the less frostbite damage my face would sustain and the sooner I could get new heating pads in my shoes and food in my mouth. It was a reckless all-or-nothing burst; if this little spot in the distance wasn't the finish, I was in trouble.

Thank God, it was. The marker at the South Pole is, well, a pole. A red-and-white-striped pole, like outside an old-fashioned barbershop. It was well past midnight as I charged toward it, heaving my chest forward in an attempt to propel my weary legs over the last bit of course. My goggles were entirely frozen over, and it was difficult to decipher anything. A snowmobile, or something, appeared before me. Actually it was Don, running in the opposite direction for some reason. At the last second I saw his hand in the air, and we high-fived each other. Apparently he was still running the half-marathon. I was in no condition to stop and ask, and we ran right past each other and kept going our own ways.

The midnight sun shone brightly overhead, be-dazzling the snow as I crossed under the makeshift finish line, throwing my exhausted arms up in celebration. It had taken nine hours and eighteen minutes to reach, and it had nearly killed me. My muscles trembled and my face felt like someone was holding a match to itâI couldn't tell whether it was hot or cold. I needed to get to shelter and get something warm in my system.

They put me on a snowmobile and shuttled me to a nearby tent, where a camp stove was heating water. Brent came in a minute later. He was thrashing and twistingâapparently his face mask was stuck to his headâand he knocked over the stove, spilling fuel across the tent floor. The floor ignited, and a fire quickly erupted inside the tent.

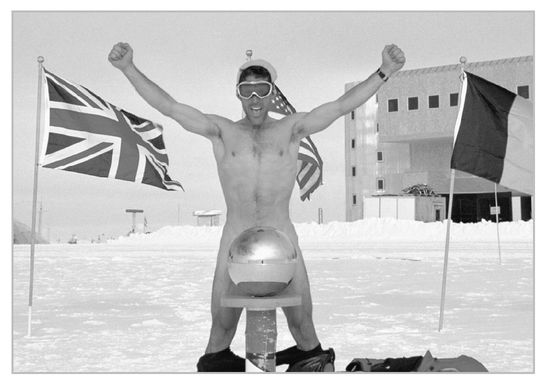

Crossing the finish line

One of the guides saw what had happened and rushed over to put out the flames. After extinguishing the fire, he tended to Brent. The face mask was frozen in place, so it had to be cut off his head with a pair of scissors.

All the while, I was dealing with the frostbite on my cheeks and nose, applying ointment and trying to warm the area. My shoes were off, and I'd wrapped my feet in a goose-down sleeping bag, trying to bring back some of the circulation.

Richard's hip flexors had seized up completely, and he had succumbed to hypothermia. He was partially snow-blind and was suffering from frostbite; he eventually received medical attention for both of those conditions and for exhaustion. The doctor administered four liters of IV fluid into Richard's arm to help revive him.

It seemed like a pretty heavy toll to pay, but, considering what we had just done, things could have been much worse. Any goal worth achieving involves an element of risk. Running a marathon to the bottom of the earth was clearly an extreme case, but the higher the risk, the grander the sense of satisfaction from accomplishing what you set out to do. We did it. And lived.

Â

Â

Â

The next morning

, before we left the Pole, Don had a wild idea: “Let's run around the world naked.” What he meant is that if we ran around the barber pole, we'd actually be circumventing the globeâat its smallest circumference, of course.

, before we left the Pole, Don had a wild idea: “Let's run around the world naked.” What he meant is that if we ran around the barber pole, we'd actually be circumventing the globeâat its smallest circumference, of course.

Despite my frostbite, I wasn't about to miss this one. So the two of us stripped to our boots and did a (quick) loop around the Pole. Now I have the dubious distinction of being the first and only person ever to run a marathon to the South Pole in running shoes, and one of only two to run around the world naked. Luckily I'd emerged from both with all appendages intact.

Just after a run around the world

ANI declared all participants equal winners and recognized each for having completed a unique challenge, and the world's inaugural South Pole Marathon was, with all its obstacles and compromises, one for the history books. Lord knows if there'd be a second one any time soon, if ever. Maybe it was just as well. It had taken nearly a month of being stuck on the ice and two tries to complete the event. We were at the top of our game, and we still barely pulled it off. The next group might not be so fortunate.

Waiting at the airport in Chile were a handful of local press. They wanted to know if I was the guy who had run to the South Pole in his tennis shoes, as they put it. One of the reporters interviewing me asked how I knew I could make it. I explained to him that I didn't know if I could make it, and that is what made the adventure so grand.

“Fantástico!”

He laughed.

“Fantástico!”

He laughed.

The flight home was overbooked and crowded. Our plane broke down in Lima, and we sat in the sweltering midsummer heat for five hours. It was a shock to my system, having just left the Antarctic sub-zero temperatures and now sitting in the tropics.

Four flights and thirty-nine hours later, I arrived home, elated that I'd made it in time. It was Alexandria's seventh birthday.

Her party was in full swing as I tiptoed through the door, the house filled with balloons, giggling girls, and birthday cake. “Surprise!” I said.

“Daddy!” she screamed, and came running over to me. We hugged and she laughed in delight; I, on the other hand, wept like a child. The emotion of seeing my family after being stranded at the bottom of the earth simply overcame me.

Other books

The Compendium of Srem by Wilson, F. Paul

Sultry Sunset by Mary Calmes

A Ship Must Die (1981) by Reeman, Douglas

Queen of the Dead by Ty Drago

Murder at the Azalea Festival by Hunter, Ellen Elizabeth

A Lovely Day to Die by Celia Fremlin

Captured Innocence (CSA Case Files) by Kennedy Layne

Yours Ever by Thomas Mallon