Under the Bloody Flag (15 page)

Read Under the Bloody Flag Online

Authors: John C Appleby

Ports and havens in the south and south-west, which had long-standing interests in maritime depredation, played a leading role in sending out men-of-war. In May 1558 Rye was described as ‘such a scourge to the French as the like is not in this realm’.

63

Further west, Dartmouth, Plymouth and neighbouring havens were heavily involved in the business of plunder. London seems to have played a modest part in the sea war. Along the east coast Newcastle also participated in sending out men-of-war. The promoters of such ventures included traders and shipowners, such as Richard Fletcher of Rye, or William and John Hawkins of Plymouth, and Hugh Offley of London. Lesser members of the gentry, including the Raleghs in the West Country, whose landed interests were complemented to some extent by interests in shipowning, were also involved in sending out armed vessels against the enemy.

64

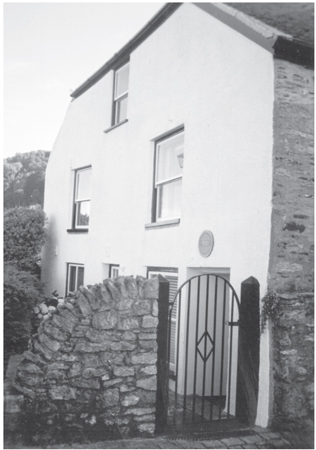

The house of John Davis, Dartmouth, Devon. Conveniently located, this modest residence was the home of one of the leading navigators and explorers of Elizabethan England, who appears to have had little interest in plunder. By contrast, Drake was able to purchase Buckland Abbey with the booty he acquired from his voyage of 1577 to 1580. (Author’s collection)

The activities of these men-of-war were heavily concentrated in the Channel and the western approaches, and usually took the form of short-distance raiding which spilled over into the spoil of vessels of varied origin. The war thus provoked widespread complaints from the victims of indiscriminate attacks, who included the subjects of Philip II. In July 1557 a Flemish adventurer complained that his ship and a French prize had been taken by the Raleghs and their associates. At the prompting of the council, both were returned with compensation for the owners. In the following month the council dealt with complaints concerning the disorderly plunder of Spanish merchants by Strangeways, and the piratical seizure of another Flemish vessel. The Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports was also involved in investigating similar allegations against adventurers based in Rye.

65

The disorder at sea appears to have intensified during 1558. The men of Rye, especially, pursued a form of enterprise that repeatedly confused the distinction between legitimate privateering and piracy. In February 1558 Richard Fletcher and his partner came to the attention of the council for the seizure of a vessel laden with a cargo from France, which was claimed as lawful prize, though the owner was an alderman of London. In March the council ordered the restoration of the

Job

of Antwerp, which had been taken by Fletcher. Towards the end of May it ordered the imprisonment of various local seamen for their disorderly conduct in a ship of the port.

66

The following month, in a case which may have been connected, Thomas Wait, shipowner, was sent by local officers to appear before the council for an offence committed at sea by one of his vessels. Despite employing spies in Rye and neighbouring ports to arrest Wait’s men, the officers informed the council that ‘[neither] ship nor any of the mariners came here since’.

67

With the war going badly, the regime faced a difficult situation at sea. The loss of Calais early in 1558 was a profound blow to the status of the Tudor monarchy. But it reflected the growing disorganization and disorder of the maritime conflict. In March the council intervened in an Admiralty case to assert that a Scottish vessel, taken by a group of adventurers in Newcastle, was lawful prize. Several weeks later, it ordered the appearance of John Asshe, gentleman and captain of the

John

of Chepstow, and John Ellyzaunder, the master of the vessel, to answer a charge of piracy for sinking a ship of Lübeck. In May it issued similar orders for the appearance of Strangeways and Thomas Stukeley. The survival of pirates such as Strangeways was accompanied by the appearance of a new group of adventurers, including Stukeley and Thomas Phetiplace who was taking French prizes off Alderney during August 1558.

68

Despite a determined effort to deal with piracy and unruly spoil, the closing months of Mary’s reign witnessed widespread complaints against the piratical activities of English men-of-war. With the war still going on, these problems were part of Mary’s legacy to her successor. In 1559, for example, John Ralegh, who was at sea in a ship owned by Hugh Wright, seized the

Hawk

of Danzig off the Scilly Isles.

69

The plunder of neutral shipping was the product of a prolonged period of disorder at sea which grew out of conflict with France during the 1540s. Weak royal rule provided greater opportunity for piratical activity to flourish. But if the later 1540s and 1550s demonstrated the inability of the mid-Tudor regime to eradicate piracy or lawlessness at sea, the period also underlined the difficulties it faced in trying to deal with an increasingly complex activity that was sustained by forces beyond its control.

The persistent disorder at sea enabled a growing number of men to earn renown or notoriety, or a mix of both, as pirates. The activities of Strangeways, one of the most notorious pirate captains operating during these years, to some extent mirrors the development of piracy, while demonstrating the challenge it presented to the mid-Tudor monarchy. In 1549 Strangeways, who probably came from Dorset, was one of Thompson’s company at Cork. By 1553 he was known to the council as the ‘Irish pirate’, though he operated on either side of the Irish Sea, plundering vessels and disposing of their cargoes locally.

70

He fled to France to avoid arrest, but in March 1554 he returned with two vessels laden with munitions and mail shirts, arriving at court in search of a pardon from the Queen. After a short spell of imprisonment, during which his portrait was evidently painted by a fellow prisoner, the German artist Gerlach Flicke, he was released, allegedly through purchasing the favours of one of the Queen’s ladies-in-waiting. Undeterred, he resumed his piratical activities, provoking Spanish complaints and claims in the High Court of Admiralty. He seems to have established contact with leading figures among the rebel rovers in France, though it is possible that he was acting as an informer. In March 1556 Thomas White recounted the troubling experiences of the Tremaynes, who were arrested for piracy and accused by Strangeways of being involved in a conspiracy against the Queen. Despite ‘being but little men in person’, White reported that they reviled Strangeways so convincingly, and in the face of either the threat or use of torture, that he ‘was ready to weep and think he had accused them wrongfully’.

71

The Tremaynes were released, and Strangeways was roundly rebuked by the council. By the later 1550s the pirate captain was in straitened circumstances. Following an Admiralty case of 1557, involving Spanish claims of £4,000, he served as one of the captains of the vessels assembled at Portsmouth for service in the Channel. The following year he was living in Dorchester, apparently poor and in great debt, though he was planning an expedition to seize the Portuguese fort at Elmina in Guinea, with the backing of a group of London merchants and the Lord Admiral.

72

Strangeways’s volatile career encapsulates the changing character of English depredation, which laid the groundwork for the emergence of more ambitious and far-reaching schemes for plunder during the 1560s and beyond. The survival of other members of his company reinforced the link between succeeding generations of pirates. In September 1559, when Strangeways was arraigned at Southwark, his accomplices included William Cheston, described as an old pirate, who had served with Coole, Thompson and Stephenson.

73

At a time of severe social and economic tension, the careers of such men suggest that the attraction of piracy and sea roving was growing, particularly among seafaring communities. With the benefit of favourable attitudes ashore, the rapid growth of hostility towards Spain during the 1550s, reinforced by commercial grievances among merchants in the south-west and London, laid out the prospect of piracy becoming a patriotic, popular and profitable enterprise.

Notes

1.

APC 1547

–

50

, pp. 130–1, 254; Rodger,

Safeguard of the Sea

, p. 195.

2.

APC 1547

–

50

, p. 155.

3.

APC 1547

–

50

, p. 131.

4.

APC 1547

–

50

, pp. 363–4, 448, 465, 467–8, 489;

CSPD Edward

, p. 45; Oppenheim

, Administration

, pp. 101–8.

5.

CSPD Edward

, pp. 59–61.

6.

CSPD

Edward

, p. 59.

7.

CSPD Edward

, p. 60.

8.

M.J.G. Stanford, ‘The Raleghs take to the Sea’,

MM

, 48 (1962), pp. 22–4; J. Youings (ed.),

Raleigh in Exeter 1985: Privateering and Colonisation in the Reign of Elizabeth I

(Exeter, 1985), pp. 94–5.

9.

Calendar

, pp. 7–8;

Tudor Proclamations

, I, pp. 444–5;

CSPI 1509

–

73

, p. 90; Stanford, ‘Raleghs take to the Sea’, pp. 24–5. According to a report of September 1549 at least 300 ships were taken, Byrne (ed.),

Lisle Letters

, I, p. 696.

10.

Calendar

, pp. 6–7;

CPR 1549

–

51

, pp. 296–8. For the Flemish response see also B.L. Beer and S.M. Jack (eds.), ‘The Letters of William, Lord Paget of Beaudesert, 1547–63’,

Camden Miscellany XXV

(Camden Society, Fourth Series, 13, 1974), pp. 42–3, 49, 68.

11.

Calendar

, p. 11; HCA 13/5, ff. 248–50; HCA 1/34, ff. 73–4, 80–1.

12.

Calendar

, p. 5.

13.

CSPI 1509

–

73

, pp. 80, 86; SP 61/1/29.

14.

CSPI 1509

–

73

, p. 81.

15.

CSPI 1509

–

73

, pp. 80, 83, 86–7, 90, 99–100.

16.

CSPI 1509

–

73

, pp. 92, 96, 100; HCA 1/34, ff. 19–22;

Tudor Proclamations

, I, p. 438. According to a report of April 1549, ‘a horde of pirates some 20 sail strong, composed of lawless men of all nations’ were ranging the coast of Ireland,

CSPF 1547

–

53

, p. 31.

17.

CSPI 1509

–

73

, pp. 100, 103.

18.

CSPI 1509

–

73

, pp. 92, 100, 107.

19.

CSPI 1509

–

73

, pp. 83, 105;

CSPD Edward

, p. 151.

20.

APC 1547

–

50

, p. 253; L.B. Smith,

Treason in Tudor England: Politics and Paranoia

(London, 1986), pp. 27–8.

21.

APC 1547

–

50

, pp. 253–4

22.

APC 1550

–

52

, pp. 29, 31, 53, 98, 112–3, 157.

23.

APC 1550

–

52

, pp. 79, 113, 148–9, 233, 354, 442, 467;

Tudor Proclamations

, I, p. 497.

24.

APC 1550

–

52

, pp. 149–50, 197.

25.

APC 1550

–

52

, pp. 369, 464;

APC 1552

–

54

, pp. 8, 10, 22, 76, 254–5 for the rest of the paragraph. D. Loades,

England’s Maritime Empire: Seapower, Commerce and Policy 1490

–

1690

(Harlow, 2000), p. 63.

26.

APC 1550

–

52

, pp. 370–1, 377, 467;

APC 1552

–

54

, pp. 57–8, 81, 174, 197, 273. J.G. Nichols (ed.),

The Diary of Henry Machyn, Citizen and Merchant

–

Taylor of London

(Camden Society, 42, 1848), p. 25 for the

Bark Aucher.

27.

Calendar

, pp. 13–4;

Select Pleas

, II, pp. 99–100.

28.

Calendar

, pp. 13–4;

CSPF 1553

–

58

, p. 231.

29.

Nichols (ed.),

Diary

, p. 4.

30.

CSPD Edward

, pp. 254, 283, 293.

31.

APC 1554

–

56

, pp. 52, 55–6, 58, 60–1, 100–4, 109, 126–7.

32.

APC 1554

–

56

, p. 151.

33.

APC 1554

–

56

, pp. 168, 183–4, 215; Oppenheim,

Administration

, pp. 110–4.