Under the Sea to the North Pole (11 page)

Read Under the Sea to the North Pole Online

Authors: Pierre Mael

At the same time a peculiarly shaped cloud was noticed on the southern horizon.

There could be little doubt but that this cloud was the smoke of the steamer. The

Polar Star

had overcome the obstacle, and was now coming full speed in search of the explorers.

A long hurrah saluted this apparition. Henceforth they were at ease. Lockwood was right. The palaeocrystic ocean did not permanently exist. The sea was open in front of the navigators who, however, knew how careful they would have to be, for those sudden clearances are quite as quickly succeeded by the return of considerable packs. Fortunately the wind varied but little, leaving the south for the south-east only, and then returning to the south.

At six o’clock in the morning the

Polar Star,

after exchanging signals with the land party, went on in advance of them towards the north. They would only see her again on the 78th parallel, which was the farthest they could go without revictualling.

On reaching this point in a temperature of fourteen degrees, the first squad went aboard the ship. This was on the 8th of May.

But thereupon the ship experienced another misfortune. The wind suddenly jumped round to the north-west, and in less than two hours, ice overspread the sea. At the same time the thermometer went down to twenty-eight degrees below zero, a really severe temperature in a season which many times already had seen the mercury at zero and even at two degrees above it.

The ship must evidently seek a refuge in some indentation in the coast. Two days were passed amid intense anxiety, for notwithstanding the lowering of the temperature, which did not stop until it stood at thirty-four degrees, a tempest sprang up, dashing the blocks against each other and against the ship.

In this truly critical situation, Captain Lacrosse suggested an essentially practical expedient. The guns of the

Polar Star

were loaded with dynamite shells, and fire was opened on the coast ice, with the same care and vigour as if on an army of human besiegers. At the same time, as there was no want of water, a jet of steam was kept playing on the floes. After thirty-eight hours of this battle of the giants, the crew, exhausted by their efforts, could enjoy a little rest, which they had well deserved.

On the 5th the march was resumed, and the steamer took advantage of a long strip of water which had opened along the coast. Going full steam ahead, they left the land expedition behind, and at a speed of fourteen knots ran the 150 kilometres which still separated them from the ,8oth degree.

There she dropped anchor. The weather was terrible.

The snow storms continued without interruption, and the cold had returned and made the working of the ship most painful.

For the first time Isabelle rather regretted her resolve.

Not that she feared for herself, although her sufferings at these times were beyond the strength of ordinary women. But the brave girl sympathized with her companions in their misery, and among them was one whose troubles appeared especially great. The nurse, Tina Le Floc’h, had not recovered from the bronchitis contracted at the beginning of the expedition, and she was now coughing in a most alarming way.

When he heard this cough. Doctor Servan became gloomy and frowned; he had done all he could for his patient, and he knew there was but one way of restoring the poor Breton to health, which was to send her back to her native land.

But unluckily they were then too far from France to hope for a sufficiently prompt return. Certainly there was not a member of the expedition who would not have sacrificed all its results to prolong the days of the good nurse. Alas! The sacrifice would have been entirely lost. Even if they were to start for the south at once, it would take three or four months for them to return to France, and that under the most favourable conditions. And in the present state of the ocean it was to be presumed that with the ice open from the north, the ship would be shut in to the south.

There was only one resource, and that was to clear out as soon as possible from the dangerous embrace of the tempest, and land on some part of the coast where it would become possible to form a summer station in which to prepare for the approaching winter.

On the loth of May, the thermometer still stood at twenty-four degrees. The snow having ceased for a little, the sky became visible. From the topmast cross-trees a good view of the surrounding landscape was obtained. It was a scene of appalling desolation.

Whither did this land of Greenland extend?

The shore was now running to the north-east. A peninsula of immense cliffs over two thousand feet high rose in an impregnable wall, and these walls of mica, schist and syenite showed not a single break, not a single port in which a ship could shelter.

At this picture a sort of religious terror was produced among the crew. A few of them were discouraged, and gave expression to this discouragement. One of them gave the coast a name, which happened to catch the fancy of the forecastle and furnish some amusement: “The barrier of the infernal!”

And never was comparison more apt. That long uninterrupted line was evil to gaze upon, and the

Polar Star

looked but a miserable straw at the foot of that mighty palisade. At the same time the strip of open water moved further out along the shore, leaving a ledge of ice three good miles in width.

The impression of weariness and superstitious fear reappeared on the 12th. The ship had been at her station at the foot of the cliff beyond the time agreed with the land party, and news of them should have arrived a day before. From the ship it was impossible to explore the elevated coast. But what was not possible to sailors on board ship might be so to travellers on foot. There was nothing to prevent them from communicating by means of firearms, and signalling their arrival in these desolate regions.

The anxiety became acute on the 13th. The land party had not reappeared, and on board everyone was in fear for them. They must have exhausted their provisions, and there was no means of taking help to them.

What could be done?

The officers held a consultation, and the boatswains were allowed to join in. Such was the general anxiety that the second boatswain, Riez, proposed that the ship should go back, and none but Lacrosse and D’Ermont could say a word against it. And this desire to retreat was encouraged by the report of the look-out, that enormous ice floes were in sight.

Captain Lacrosse, bitter at heart, was about to give the necessary orders for this movement to the rear, when Isabelle entered the saloon.

It had come to be the custom to speak openly before her, and to conceal nothing of the decisions that had been arrived at. In a few embarrassed words Lacrosse told her of the determination to which they had just been led.

He could not help showing that he was not of the opinion of the majority.

“As for me,” he said, “I have always thought that the man who advances has far more chances than the man who retreats, and that to say nothing of courage, our very . interest counsels us to remain here and not to go back.”

Isabelle waited only for this. She exploded.

“What!” she exclaimed. “Are we to be stopped by this? What! Because we are in face of a disquieting probability, are we to give up without a fight a position we have won, a victory which everything promises us? Do you not see that to retreat is to irretrievably ruin the expedition? We must do one of two things. Either we return direct to France; or we return to Cape Ritter. In that case what do we gain? A retreat of four degrees cannot improve our position. We are at the gate of the fine season, and less than one hundred and sixty miles from the point which Lockwood and Brainard, in want of provisions, reached on foot. We have provisions in abundance, and more, we have means which none before us possessed, and we have verified their efficiency. Are we to give up the game? Are we to declare ourselves beaten at the first obstacle? Can you not see that this cliff must be nearing its end, and that by the very nature of the soil this rocky coast must give place to low lands much cut into? Is it for me to remind you that schistose rocks are but accidents of the ground, intermittent upheavals of the terrestrial crust? To-morrow, after to-morrow, or later, the sun will raise the temperature and the sea will be open; the floe that has just been reported can but be a last patch of the pack we have just traversed.”

She spoke with emotion, with communicative conviction. The company hesitated. A final argument overcame all resistance. She continued,—

“And our friends, our brothers on the land, are we to abandon them? Why search for them towards the south, when they are much more likely to have gone towards the north?”

She was right. There was every likelihood that the explorers, finding it difficult to keep to the cliffs, had cut across the peninsula. To retreat was to leave them without provisions on this inhospitable shore.

“Come, gentlemen,” concluded Isabelle, supplicatively, holding out her hands, “one more effort, one only; everything tells me that we shall soon reach the end of this rocky wall, for some more favourable cape that the mist now hides from us; and that under the 81st parallel. Come! Cheer up for our own glory and for that of France!”

The men rose as if they were electrified. One shout gave they all,—

“ Forward! for the honour of France.”

And Captain Lacrosse, going on deck, gave orders for more steam.

Isabelle was right, and once again the adage that “Fortune favours the bold” was justified. The pack that had been sighted seemed to clear away from the

Polar Star,

and the sun emerging from the mist showed a blue sea on which there was but a floeberg here and there.

Ten miles to the north-west they could perceive the extremity of the cliff ending in a low narrow cape. The steamer was hurried along to it at fifteen knots. When she reached the end of the promontory the radiant ocean extended out of sight to the north, while the Greenland coast ran away to the north-west.

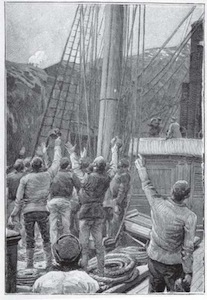

Suddenly, in the silence of admiration which followed this discovery, there was a report. The eyes of all turned towards the coast. A puff of white cloud rose on the crest of the lowest cliffs. The explorers were there.

On the deck of the

Polar Star

excited cheers responded to the shot, and the ship, nearing the shore, cast anchor beyond the point so gloriously doubled.

“This cape,” said Captain Lacrosse, “can only bear one name, that of the heroic woman who inspired us with courage. We will call it henceforward, Cape Isabelle.”

Again there was a triple round of clapping. Then two boats left the ship and reached the sandy shore of a lovely bay. Half-an-hour later the whole of Lieutenant Hardy’s men were on board; and a third detachment took their places.

The voyage was then resumed on a favouring sea. Twice again did the

Polar Star

put in for the purpose of relieving the detachments. At last, on the 28th of May, four weeks after the

departure from Cape Ritter, the steamer dropped anchor at the most northerly point of Greenland in 83° 54' i2". There the coast ran off to the south-west. On the horizon was a bay, which they recognized at once as the eastern arm of Conger Inlet in Hunt Fiord. Lockwood Island was in the centre, and at the end of the wonderful panorama were the black rocks of Cape Alexander Ramsay.

They had reached the promontory which the two heroes of the Greely expedition had named, without being able to reach it, after a name dear to all American hearts. This was Cape Washington. Up to the present all competitors had been distanced. France had gone farther than all.

The delight of the crew was boundless; it almost reached delirium. They shouted, they wept, they kissed each other. Some of the sailors began stamping their feet, walking on their hands, and dancing most fantastically. Now they believed themselves sure of final success. They had but 6° 4' or 606 kilometres, and they would reach the Pole itself.

The sky continued propitious. This coast which Lock-wood and Brainard had found bordered with ice in 1882, but which they had seen the ice break away from the following year, was now free from its frigid girdle.

The first work to be done was to complete the map. It took six long days, but this was permissible to explorers who had been over the whole of the ground. Although the heat was not as great as usual, the year promised to be exceptionally mild, and the thermometer quickly rose to really extraordinary levels. The temperature, which at first did not exceed nine degrees, stood on the 8th of June at sixteen and on the loth at eighteen; so that there were complaints of the heat of the sun.

But this abnormal rise was, of great service to the travellers. In the first place it allowed of excursions into the interior and along the coast. They were thus enabled to discover that the arm of the sea called Hunt Fiord by Lockwood, was a regular gulf between Cape Washington and Cape Kane, from the latter of which began a series of cliffs forming the coast of Conger Channel, which in turn communicates with Weyprecht Fiord, to the south-east of Lockwood Island. Beyond this island they could see no further than the extreme point of Cape Ramsay, but they recognized with scrupulous care all the discoveries of their predecessors. Hazen Land, terminated by Capes Neumayer and Hoffmeyer and bounded by Wild and Long fiords. The vegetation on these different tablelands appeared strangely abundant for such latitudes. The presence of bears and musk oxen led to profitable hunting expeditions, to say nothing of lucky shots at eider ducks, ptarmigan, dovekies and lagopedes. Finally, on the i2th of June, with the sea open to the north, it was decided to land, and build the house in preparation for the second wintering.