Under the Sea to the North Pole (23 page)

Read Under the Sea to the North Pole Online

Authors: Pierre Mael

Henceforth it would be known not only in the world of science, but in the ordinary world, that the North Pole is an island where there reigns a spring climate due to the combined influence of solar rays and magnetic effluences; that this island is washed by an open sea separated into two zones by a wall of rocks surmounted by perennial ice, and that it is not impossible to discover in this wall the fissures, by which the two concentric circles of the palaeocrystic ocean communicate. Perhaps this passage might allow of a ship reaching the centre of the globe.

It was also known that a series of subterranean and submarine passages put in communication not only the two seas but the arctic lands and the Pole itself, and that travellers availing themselves of the same means could repeat the adventurous attempt which two men- and a woman had conducted so successfully.

These reflections poured sweet consolation into the hearts of the explorers. Said Hubert,—

“We have not yet finished our work. We have to carry our boat to the edge of the walls of rock, and that is not going to be easy.”

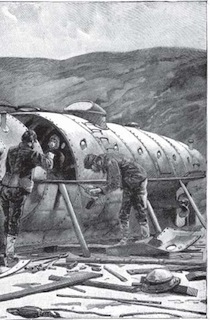

It was a very long affair. It took ten hours to take the boat to pieces, to carry her, and to put her together again.

The worst part of the task was the transport of the pieces over the ragged slippery icebergs. Nevertheless at the end of the ten hours the boat was peacefully afloat on the waves of the open sea, and the three companions, now sure of return, had moored her in the shelter of some high rocks while they went to sleep.

When this well-earned rest was over, Hubert accurately fixed the position of the subterranean tunnel.

It was in 41° 48" longitude west from Paris.

Twelve entire days had elapsed since their departure, when the bold explorers came alongside the field of ice on which their friends awaited them. Three of them only were there. The others had been prudently sent back, and among them De Keralio.

Lieutenant Pol, Doctor Servan and a sailor had remained behind at their dangerous post on the ice.

They had with them a sledge and the team of dogs required to draw it. The first living being to welcome the travellers was the brave Salvator. They could not keep him away. He threw himself into the sea and swam out to meet the boat, into which Guerbraz and Isabelle helped him.

The brave dog was enthusiastic in his demonstrations. His transports of joy were indescribable. It seemed that he would never be satisfied at the sight of Isabelle. While by his barking, his jumping and his caressing he manifested his joy at her return.

They were no longer in the mild atmosphere of the Pole; they

had again entered the kingdom of the cold.

The journey to Courbet Island was laborious beyond expression in a temperature of about 40 degrees below zero. But the happiness of returning to the station, the satisfaction of having surmounted all obstacles, sustained the strength and courage of the little troop. On the 20th of September, after having been met by a rescue party from the ship, they at length reached the

Polar Star.

Alas! bad news awaited them. Not only did they learn of the treason and ill-omened projects of Schnecker; but they also heard that two sailors had died. They had also the sorrow of hearing bad news from Cape Washington, where death had removed two men from the ranks, and, what affected Isabelle more than anything else, Tina Le Floc’h was very ill on board the ship, and Doctor Le Sieur did not think she would survive many days.

The expedition’s second wintering, in spite of the success obtained, had begun under the most melancholy auspices.

CHAPTER XV

A SIEGE.

A

SSUREDLY the actual position of the expedition was as good as it could be. The

Polar Star

was in excellent shelter at Long Creek, and safe from the outside storms and the shocks of the ice field. Solidly fixed in her cradle, and guarded by two high walls of syenite, she had but to wait for the end of the bad weather to resume the voyage to France, through the seas to the south of her.

There was no scarcity of provisions; independently of the reserve of liquefied hydrogen, they had enough coal for the daily heating. There would also be plenty of light, and if they did not possess the same abundance of fresh provisions, if they were wanting in the marvellous resources of the mould improvised the winter before, they had still preserved things enough to furnish all the requirements of the most voracious appetite.

Besides, the hunters had not lost hope of some fortunate shooting before the return of the formidable polar night. They had even received from Cape Washington the glad tidings of the presence of game as varied as numerous for the guns in the autumn campaign.

There was, therefore, no need to be anxious about the men who were in good health.

Unfortunately they were not all in good spirits. The thought of the deaths occurring so quickly one after the other had clouded their brows and relaxed their energies. They had learnt, on De Keralio’s return, what had been the lot of his two companions in bravery and misery. Besides, a few cases of scurvy had appeared, soon complicated by exhausting diarrhoea, which if it did nothing else, reduced the sufferers to a state of physical weakness and intellectual destitution.

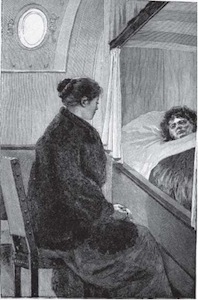

Isabelle had at once begun to look after the sick, and she had enough to do. She was everywhere dispensing medicine and comfort and hope. But she herself wanted all her courage to reanimate that of her companions, in the presence of her own private sorrow concerning the illness of her nurse Tina Le Floc’h.

The poor Breton was lost, and she knew it. With admirable resignation she yielded to the decree which deprived her of the days she might have lived in sunny France. She had not a bitter word,, but her face showed the joy she felt at having near her the child she had nourished, and to whom she had been a second mother.

Painfully she dragged out this doomed existence between the plank walls of this stationary house, in this atmosphere so little favourable for respiration, in the factitious light of electric lamps. The polar night seemed to weigh on her more heavily than on others, but she submitted without a murmur.

The winter was of extreme severity. The great cold of the preceding year was exceeded. On the 20th of November the mercury in the thermometer was frozen. On the 1st of December it was the turn of the acids and alcohols to thicken into a sort of syrup. From that date the temperature remained almost constantly at 40 degrees below zero. In the early days of January it descended to levels, in which the cold was tremendous: 50, 52, 54, 56 degrees below zero. The most careful medical precautions were ordered and taken; the men were forbidden to go out, and kept indoors for an entire week.

Then the coal fires were withdrawn and hydrogen was burnt in the stoves, in the forecastle and cabins; and in this way a constant temperature was maintained of four degrees.

Fortunately, if the winter was terrible it was also relatively short.

On the 15th of January the temperature suddenly mounted to the freezing point of mercury. At the same time an increase of barometric pressure announced the arrival of a storm from the south.

It lasted two days and was terrible. Notwithstanding her sheltered position, the

Polar Star

had a narrow escape.

An enormous piece of rock fell down from the cliff, and smashing the mizen top crashed to the deck. Among the cabins damaged by this accident were those of Isabelle and her nurse. This fall also cost the lives of two sailors. One was killed on the spot, and the other had his legs broken, and died after an amputation which was inevitable. These were causes of grief which the return of the sun was not likely to dissipate.

When February came the cold was not much more than from twenty-five to thirty-two degrees. As a change for the men Captain Lacrosse ordered them out on expeditions. The first detachment, under the command of the valiant Guerbraz, went off to Cape Washington and reached it after six days’ hard work. He left there two of his men and brought back serious news. Lieutenant Remois had succumbed to an internal complaint due to the extreme cold, and with him two sailors, both Canadians, had died.

These three deaths made up the number of the victims of the expedition to twelve.

There remained thirty-one men and two women. A conference took place on board the ship to decide if they should maintain the two stations. It seemed in fact to be more practical and. more prudent to unite the crew either on the steamer or in the house at Cape Washington. That would make it easier to attend to the invalids, and enable the two doctors to work together. And what was a valuable advantage, it would considerably reduce the expenditure of light and fuel.

It was decided to recall the men from the southern station, and bring them as soon as possible on board the

Polar Star.

A consultation also took place with regard to the fate of Schnecker, who had all the time been under guard.

Pronounced guilty unanimously, and condemned to death, the chemist only owed his safety to the prayers of Isabelle, who presented herself with tears in her eyes before his judges.

“Gentlemen,” she said, “I only bring forward one thing to induce you to be merciful. Twelve of us have already died on the field of honour of our enterprise. Others, whose number we as yet know not, will probably die before long, and my heart is already in mourning for a life which is particularly dear to me. I entreat you, by the execution of a sentence as rigorous as it is just, not to add a new means to those by which death has mowed into our ranks. Do not let a stain of blood, however honourable, rest on your hands. I know that the man is a scoundrel, and that he has attempted the lives of us all and of everyone in the ship. I know that through his crime two of our bravest are dead, and that the chief of our expedition, my father himself, has been the victim of veritable attempt at assassination directed against him by this wretch. But I would forget his crimes in the remembrance of the services he has rendered, and above all that this man has been the companion of our sufferings and our efforts. Give him time to realize the greatness of his crime and to repent.”