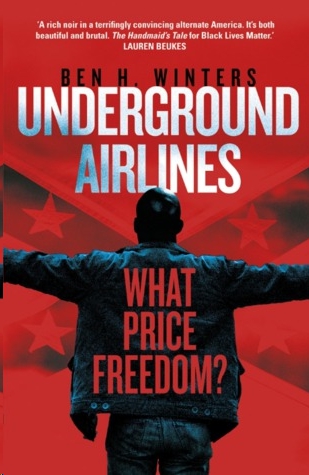

Underground Airlines

Read Underground Airlines Online

Authors: Ben Winters

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

For my kids, and their friends

No future amendment of the Constitution shall affect the five preceding articles…and no amendment shall be made to the Constitution which shall authorize or give to Congress any power to abolish or interfere with slavery in any of the States by whose laws it is, or may be, allowed or permitted.

—From the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. It is the last of six amendments that, together with four congressional resolutions, make up the so-called Crittenden Compromise, proposed by Senator John J. Crittenden of Kentucky on December 18, 1860, and ratified by Congress on May 9, 1861

It is a strange kind of fire, the fire of self-righteousness, which gives us such pleasure by its warmth but does so little to banish the darkness.

—Augustin Craig White, from

The Dark Tower,

a pamphlet of the American Abolitionist Society, 1911

“So,” said

the young priest. “I think that I’m the man you’re looking for.”

“Oh, I hope so,” I said to him. “Oh, Lord, I do hope you are.”

I knitted my fingers together and leaned forward across the table. I was aware of how I looked: I looked pathetic. Eager, nervous, confessional. I could feel my thin, cheap spectacles slipping down my nose. I could feel my needfulness dripping from my brow. I took a breath, but before I could speak, the waitress came over to pour our coffee and hand out the menus, and Father Barton and I went silent, smiled stiff and polite at the girl and at each other.

Then, when she was gone, Father Barton talked before I could.

“Well, I must say, Mr. Dirkson—”

“Go on and call me Jim, Father. Jim’s just fine.”

“I must say, you gave LuEllen quite a start.”

I looked down, embarrassed. LuEllen was the receptionist, church secretary, what have you. White-haired, apple-cheeked lady, sitting behind her desk at that big church up there on Meridian Street, Saint Catherine’s, and I suppose I behaved like a wild thing in her tidy little office that afternoon, gnashing my teeth and carrying on. Throwing myself on her mercy. Pleading for an appointment with the father. It worked, though. Here we were, breaking bread together, the gentle young priest and I. If there’s one thing they understand, these church folks, it’s wailing and lamentation.

But I bowed my head and apologized to Father Barton for the scene I’d caused. I told him to please carry my apologies to Ms. LuEllen. And then I brought my voice way down to a whisper.

“Listen, I’m just gonna be honest with you and say it, sir. I’m a desperate man. I got nowhere else to turn.”

“Yes, I see. I do see. I only wish…” The priest looked at me solemnly. “I only wish there was something I could do.”

“What?”

He was shaking his head, and I felt my face get shocked. I felt my eyes get wide. I felt my skin getting hot and tight on my cheeks. “Wait, wait. Hold on, now, Father. I ain’t even—”

Father Barton raised one hand gently, palm out, and I hushed up. The waitress had come back to take our orders. I can remember that moment perfectly, can picture the restaurant, dusk-lit through its big windows. The Fountain Diner was the place, a nice family-style place, in what they call the Near Northside, in Indianapolis, Indiana. On that same Meridian Street as the church, about fifty blocks farther downtown. Handsome, boyish Barton there across from me, no more than thirty years old, a tousle of blond hair, blue Irish eyes, pale skin glowing like it had been scrubbed. Our table was right in the center of the restaurant, and there was a big ceiling fan high above us, its blades turning lazily around and around. The bright, sizzling smell of something frying, the low ting-ting of forks and knives. There were three old ladies at the booth behind us with thin beauty-shop hair and red lipstick, their walkers parked in a neat row like waiting carriages. There was a pair of policemen, one black and one white, in a corner booth. The black cop was leaning halfway across the table to look at something on the white one’s phone, the two of them chortling over some policeman joke.

Somehow I got through ordering my food, and when the waitress went away the priest launched into a speech as carefully crafted as any homily. “I fear that you have gotten the wrong impression, which of course is in no way your fault.” He was speaking very softly. We were both of us aware of those cops. “I know what people say, but it’s not true. I’ve never been involved in…in…in those sorts of activities. I’m sorry, my friend.” He placed his hand gently over mine. “I am terribly sorry.”

And he

sounded

sorry. Oh, he did. His calm Catholic voice glowed with gentle apology. He squeezed my hands as a real father would, never mind that I was a decade or more his senior. “I know this is not what you wanted to hear.”

“But—wait, now, Father, hold on a moment. You’re here. You came.”

“Out of compassion,” he said. “Compassion compelled me.”

“Oh, Lord.” I leaned away from him, feeling like a damn fool, and dropped my face into my hands. My heart was trembling. “Lord almighty.”

“You have my sympathy, and you have my prayers.” When I looked up his eyes were straight on me and steady, crystal blue and radiating kindness. “But I must be truthful and say there is nothing else that I can offer you.”

He watched me, unblinking, waiting for me to nod and say, “I understand.” Waiting for me to give up. But I couldn’t give up. How could I?

“Listen. Just—I am a free man, as you see, sir, legally so,” I said, then charging on before he could interrupt. “Manumitted years ago, thanks to the good Lord in heaven and my master’s merciful last will and testament. I have my papers; my papers are in order. I got my high school equivalency, and I’m working, sir, a good job, and I’m in no kind of trouble. It’s my wife, sir, my

wife.

I have searched for years to find her, and I’ve found her. I tracked her down, sir!”

“I understand,” said Father Barton, grimacing, shaking his head. “But…Jim—”

“She is called Gentle, sir. Her name’s Gentle. She is thirty-three years old, thirty-three or thirty-four. I—” I stopped, blinking away tears, gathering my dignity. “I’m afraid I have no photograph.”

“Please. Jim.

Please.”

He spread his hands. My mouth was dry. I licked my lips. The fan turned overhead, disinterested. One of the cops, the white one, thick-necked and pink-skinned, reared back and slapped the table, cracking up at something his black partner had said.

I held myself steady and let my eyes bore into the priest’s. Let him see me clear, hear me properly.

“Gentle is at a strip mine in western Carolina, sir. The conditions are of the utmost privation. Her owner employs overseers, sir, of the cruelest stripe, from one of these services—you know, private contractors. And, now, this mine—I’ve been looking, Father, and this mine has been sanctioned half a dozen times by the BLP. They’ve been fined, you know, paid millions in these fines, for treatment violations, but you…you know how it is with these fines, it’s a drop in the—you know, it’s a drop in the bucket.” Barton was shaking his head, gritting his teeth emphatically, but I wouldn’t stop—I couldn’t stop—my words had become a hot rush by then, fervent and angry. “Now, this mine, this is a

bauxite

mine, and a female PB, one of her age and…and her weight, you see? According to the law, you see—”

“Please, Jim.”

Father Barton tapped his fingertips twice on the table, a small but firm gesture, like he was calling me to order or calling me to heel. The compassionate glow in his voice was beginning to dim. “You need to listen to me, now. We don’t

do

it. I know what is said of me and of my church. I do. And I believe in the Cause, and the church believes in the Cause, as a matter of policy and faith. I have spoken on it and will continue to speak on it, but speaking is all that I do.” He shook his young head again, looked quickly at me and then away, away from my frustration and grief. “I feel deeply for your situation, and my prayers are with you and your wife. But I cannot be her savior.”

I was silent then. I had more words, but I swallowed them. This was a bitter result.

I got through our brief supper as best I could, keeping my eyes on my plate, on my fish sandwich and coleslaw and iced tea. God only knows what I’d been expecting. Surely I had not imagined that this man, this

child,

would be so moved by the plight of my suffering Gentle that he would leap to his feet and charge southward with pistols bared; that he would muster up a posse to kick in the doors of a Carolina bauxite mine; that he would take out his cell phone and summon up the army of abolition.