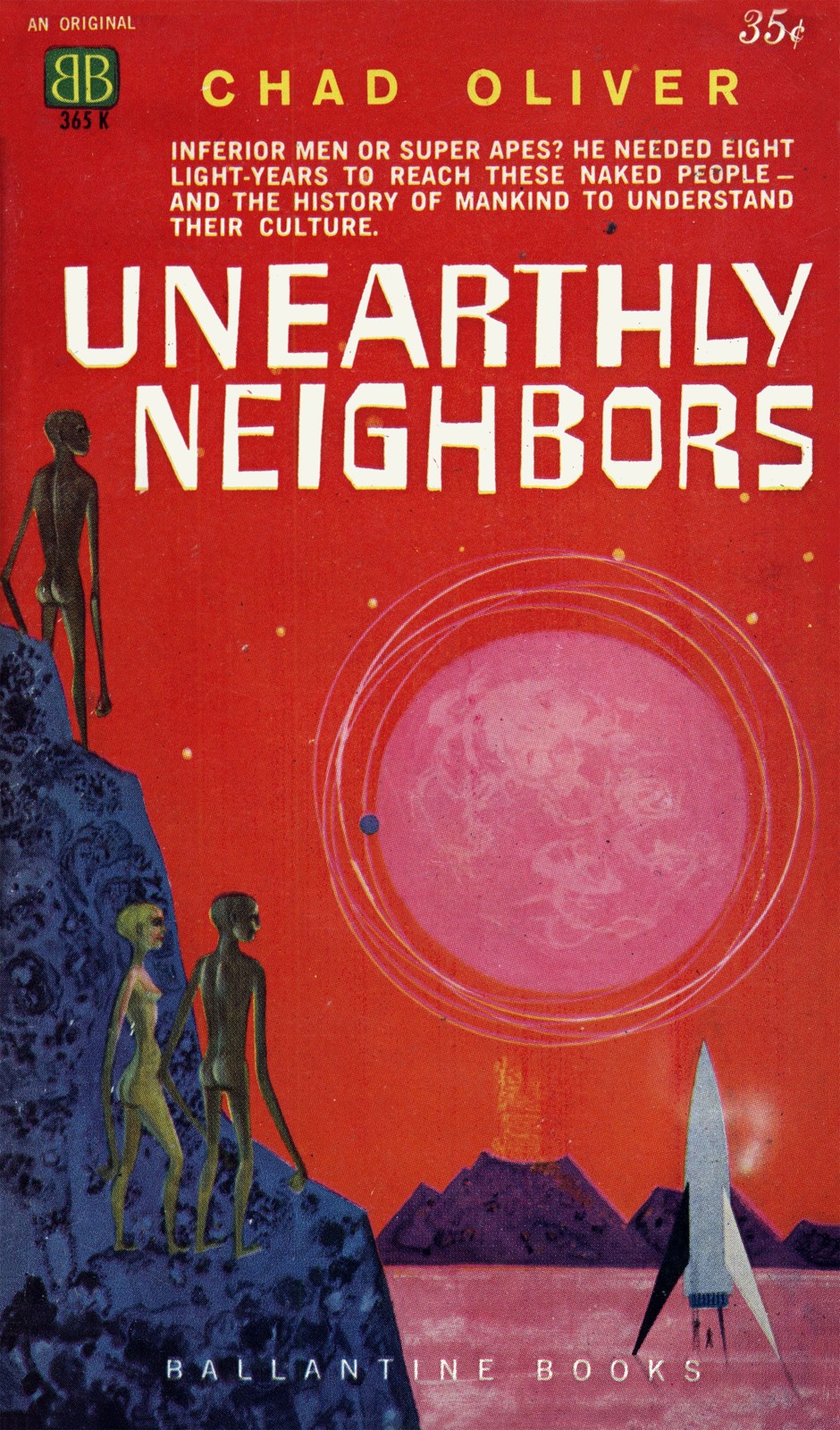

Unearthly Neighbors

Read Unearthly Neighbors Online

Authors: Chad Oliver

IN CHAD OLIVER, anthropology, science fiction and good writing have found a happy catalyst. Mr. Oliver works himself in that field of the sciences which is the study of man (or kinds of man), has the imagination to project anthropological problems into science-fiction terms, and the writing ability to create solid, believable and moving characters, trying to solve problems which man has been tackling since the world began.

In Unearthly Neighbors, Chad Oliver comes to grips with what it might really be like to investigate an alien life-form. He makes it clear that this is not going to be easy. He does not “pretty up” his story. But he demonstrates the reality of courage and despair, of hope and defeat, and in the end, of that imperfection in man which is the saving of the human, and other, races.

Copyright © 1960 by Chad Oliver

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Ballantine Books, Inc.

101 Fifth Avenue, New York 3, New York

Unearthly Neighbors

High above the tossing trees that were the roof of the world, the tierce white sun burned in a wind-swept sky.

Alone in the cool, mottled shade of the forest floor, the naked man sat with his back resting against his tree and listened to the sigh of the woods around him. He was an old man now, old with the weight of too many years, and his thoughts were troubled.

He lifted his long right arm and held it before him. There was strength in Volmay yet; the muscles in his arm were firm and supple. He could still climb high if he chose, still dive for the strong branches far below, still feel the intoxicating rush of the air in his face…

He let the arm drop.

It was not only Volmay’s body that was old; the body mattered little. No, it was Volmay’s

thoughts

that worried him. There was a bitter irony about it, really. A man worked and studied all his life so that one day he would be at peace with himself, all duties done, all questions answered, all dreams explained. And then…

He shook his head.

It was true that he was alone, but all of the People were much alone. It was true that his children were gone, but they were good children and he could see them if he wished. It was true that his mate no longer called out to him when the blood pulsed with the fevers of the spring, but that was as it should be. It was true that he had only a few years of life remaining to him, but life no longer seemed as precious to Volmay as it had in the lost, sunlit years.

He looked up at a fugitive patch of blue sky that showed through the red leaves of the trees. He had walked life’s long pathway as it was meant to be walked, and he knew what there was to know. He had not been surprised—except once—and he had not been afraid.

And yet, strangely, he was not content.

Perhaps, he thought, it was only the weight of the years that whispered to him; it was said that the old ones had one eye in the Dream. Or perhaps it had been that one surprise, that one glimpse of the thing that glinted silver in the sky…

But there was

something

within him that was unsatisfied and unfulfilled. He felt that his life had somehow tricked him, cheated him. There was something within him that was like an ache in his heart.

How could that be?

Volmay closed his dark eyes, seeking the dream-state. The dream wisdom would come, of course, and that was good. But he already knew what he would dream; he was not a child…

Volmay stirred restlessly.

The great white sun drifted down the arc of afternoon. The wind died away and the trees grew still.

The naked man dreamed.

And—perhaps—he waited.

“Free will?” Monte Stewart chuckled and tugged at his untidy beard. “What the devil do you mean by that?”

The student who had imprudently expressed a desire to major in anthropology had a tough time in choking off his flood of impassioned rhetoric, but he managed it. “Free will?” he echoed. He waved his hand aimlessly. “Well—uh—you know.”

“Yes, I know.” Monte Stewart leaned back precariously in his swivel chair and stabbed a finger at the eager young man. “But do

you

know?”

The student, whose name was Holloway, was obviously unaccustomed to having his glib generalities questioned. He fumbled around for a moment and then essayed a reply. “I mean that we have the ability to choose, to shape our own Destiny.” (Halloway was the type that always capitalized words like Fate and Destiny and Purpose.)

Monte Stewart snorted. He picked up a dry human skull from his desk and flapped the spring-articulated mandible up and down. “Words, my friend, just words.” He cocked a moderately bushy eyebrow. “What type blood do you have, Mr. Halloway?”

“Blood, sir? Why—Type O, I think.”

“When did you make the choice, Halloway? Prior to your conception or later?”

Halloway looked shocked. “I didn’t mean—”

“I see that your hair is brown. Did you dye it, or merely select the proper genotype?”

“That’s not fair, Dr. Stewart. I didn’t mean—”

“What didn’t you mean?”

“I didn’t mean free will in

everything,

not in biology. I meant free will in the choices we make in everyday life. You know…”

Monte Stewart sighed. He fished out his pipe from a cluttered desk drawer and clamped it between his teeth. One of his most cherished illusions was that students should learn how to think; Halloway might as well start now. “I notice, Halloway, that you are wearing a shirt with a most admirable tie, a pair of slacks, and shoes. Why didn’t you put on a G-string and moccasins this morning?”

“Well, sir, after all—”

“Your presence in my class indicates that you are technically a student at the University of Colorado. If you had been born an Australian aborigine, you would instead be learning the mysteries of the

churinga.

Isn’t that so?”

“That may be, but just the same-—”

“Have you had supper yet, Halloway?”

“No, sir.”

“Do you think you are likely to choose fermented mare’s milk mixed with blood for your evening meal?”

“I guess not. But I could, couldn’t I?”

“Where would you get it this side of the Kazaks? Have you ever considered the fact that a belief in free will is a primary prop of the culture you happened to grow up in? Has it ever occurred to you that if the concept were not present in your culture you wouldn’t believe in it—and that your present acceptance of it is

not

a matter of free choice on your part? Have you ever toyed with the notion that

any

choice you may make is inevitably the product of the brain you inherited and what has happened to that brain during the time you have been living in a culture you did not create?”

Halloway blinked.

Monte Stewart stood up. He was not a tall man, but he was tough and wiry. Halloway got up too. “Mr. Halloway, do you realize that even the spacing between us now is culturally determined—that if we were members of a different cultural system we would be standing either closer together or further apart? Come back and see me again in two weeks and we’ll talk some more.” Halloway backed toward the door. “Thank you, sir.”

“You’re entirely welcome.”

When the door closed behind Halloway, Monte grinned. Even with his rather formidable beard, the grin was oddly boyish. He had been having a good time. Of course, any moderately sophisticated bonehead could have given him an argument on the old free will problem, but Halloway—although he qualified at present as a bonehead—was not even moderately sophisticated. Nevertheless, the boy had possibilities, if he would just stop coasting and start thinking. Monte had seen it happen before—that startling transition from wide-eyed undergraduate to dogmatically certain graduate and, sometimes, on to the searching questions that were the beginnings of wisdom.

Monte enjoyed his teaching and got a kick out of his reputation as a fearsome ogre. The experience of finding a student with real potential was a rewarding one, second only to the thrill of solving a rough problem in population genetics or probing into the mysteries of the culture process itself. Monte liked his work; which made him practically unique in the modern world.

He walked over to the projector, a surprisingly dapper man despite the hit-or-miss casualness of his suit. His short black hair was neat and trim, complementing the slight shagginess of his jutting spade beard. His clear gray eyes were bright and alert, and although he looked his age—which was a year shy of forty—he conveyed the impression that it was a pretty good age to be.

He flipped on the projector, testing it for tomorrow morning’s freshman class. The three-dimensional picture took shape in the air, without a screen, and there was old Mr. Neanderthal in profile—supraorbital ridges, occipital torus, and all. He turned off the projector, thus effectively returning

Homo neanderthalensis

to the Third Interglacial.

Since his stomach informed him that it was time to be heading for home, he locked up his smoke-hazed office and rode the elevator up to the roof of the Anthropology Building. (It was not one of the larger buildings on the campus, but the status of anthropology in 1991 had improved to the point where it was no longer possible to dump the department into an improvised shack.) The cold Colorado air was bracing, and he felt fine as he climbed into his copter and took off.

He lazed along in the traffic of the middle layer, enjoying the glint of snow on the mountains and the clean golden light of the westering sun. It had been a pretty good day for a Wednesday, and it had been easy. Indeed, if anything, it had been too easy. A considerable part of Monte’s irritation with other people was due to their frequent inability to fire an idea his way that he hadn’t heard fifty times before. Monte needed stimulation; he lived on it. He didn’t give two hoots in a rain barrel for his reputation as one of the four or five top men in his field, but he

did

relish new problems. Once he had cracked a problem to his own satisfaction he tended to lose interest in it. He appreciated new points of view for the simple reason that life was too short to waste it on boredom.

He eased the copter down toward his tasteful rock-and-log home in the foothills of the mountains, and was surprised to see an unfamiliar copter parked on the roof right next to his garage. He landed, climbed out, and took a good look at it. It was an expensive green Cadillac, and it had the official U.N. insignia on its tags.

This, he decided, might be interesting.

The top door of his home opened before him, and Monte Stewart hurried down the stairs to see what was going on.

The man was seated in Monte’s favorite chair in the living room, enjoying what appeared to be a Scotch and soda. Both of these choices, in Monte’s view, indicated a man of intelligence. He stood up when Monte entered the room, and Monte recognized him at once. He had never actually met the man, but his craggy face and silver-gray hair were immediately familiar to any tri-di watcher.

“You’re Mark Heidelman,” he said, extending his hand. “This is an unexpected pleasure; I’m Monte Stewart. Did you send a letter or something I didn’t get?”

Mark Heidelman shook hands with a solid, no-nonsense grip. “The pleasure is mine, Dr. Stewart. No, I didn’t write—I just barged in on you. It’s pretty shoddy procedure for a diplomat, but this visit is on the hush-hush side. I hope you’ll excuse it when you find out why I’ve come. I took the liberty of coming to your home because this concerns your wife as well as yourself. She’s certainly a lovely woman, by the way.”

Monte waved him back to his chair and pulled up another one. “I like her,” he admitted. “This is an official visit, then?”