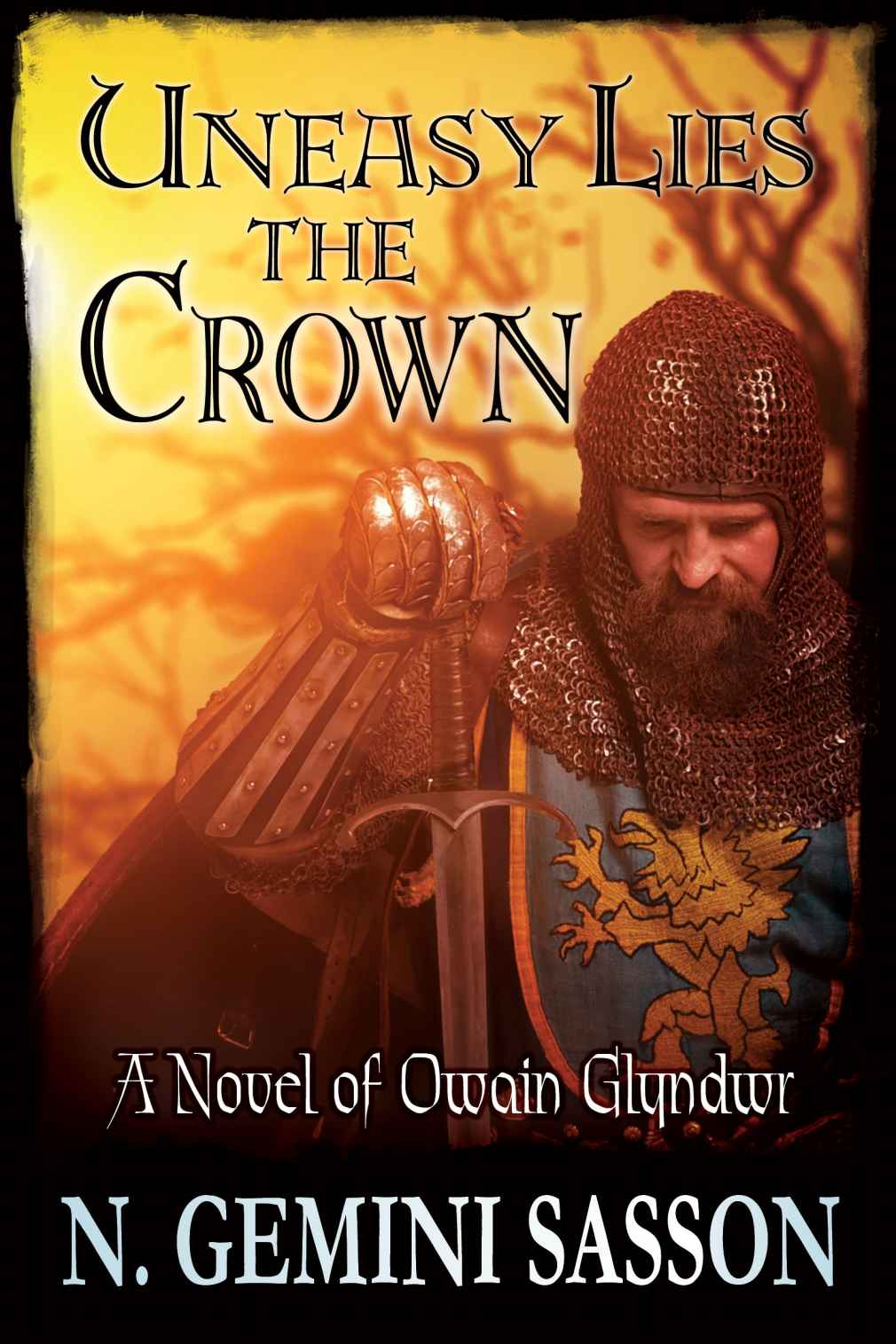

Uneasy Lies the Crown

Read Uneasy Lies the Crown Online

Authors: N. Gemini Sasson

Table of Contents

Some Welsh Pronunciation and Words

UNEASY LIES

THE

CROWN

A Novel of Owain Glyndwr

N. GEMINI SASSON

Cader Idris Press

UNEASY LIES THE CROWN

A Novel of Owain Glyndwr

For centuries, the bards have sung of King Arthur’s return,

but is this reluctant warrior prince the answer to those prophecies?

In the year 1399, Welsh nobleman Owain Glyndwr is living out a peaceful gentleman’s life in the Dee Valley of Wales with his wife Margaret and their eleven children. But when Henry of Bolingbroke, the Duke of Lancaster, usurps the throne of England from his cousin Richard II, that tranquility is forever shattered. What starts as a feud with a neighboring English lord over a strip of land evolves into something greater—a fight for the very independence of Wales.

Leading his crude army of Welshmen against armor-clad columns of English, Owain wins key victories over his enemies. After a harrowing encounter on the misty slopes of Cadair Idris, the English knight Harry Hotspur offers Owain a pact he cannot resist.

Peace, however, comes with a price. As tragedies mount, Owain questions whether he can find the strength within himself not only to challenge the most powerful monarch of his time, but to fulfill the prophecies and lead his people to freedom without destroying those around him.

UNEASY LIES THE CROWN,

A NOVEL OF OWAIN GLYNDWR

(Kindle Edition)

Copyright © 2012 N. Gemini Sasson

This is a work of fiction. The names, characters, and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the Author.

For more information about the author:

www.ngeminisasson.com

For updates on N. Gemini Sasson’s books:

www.facebook.com/NGeminiSasson

Cover art by Lance Ganey:

www.freelanceganey.com

Also by N. Gemini Sasson:

Isabeau, A Novel of Queen Isabella and Sir Roger Mortimer

The King Must Die, A Novel of Edward III

The Crown in the Heather (The Bruce Trilogy: Book I)

Worth Dying For (The Bruce Trilogy: Book II)

The Honor Due a King (The Bruce Trilogy: Book III)

AUTHOR’S NOTE

In the latter part of the thirteenth century, Edward I of the Plantagenet dynasty rose to the throne of England. King Edward I, or Longshanks as he was later known, was determined to secure his borders and bring the whole Isle of Britain under his domain. He subdued the Welsh by hiring the brilliant James of St. George to design and erect formidable castles throughout Wales and he also invaded Scotland innumerable times, finally setting the pliable John Balliol on the throne of that country. While Scotland struggled for its independence, Wales lay in a state of tacit subjugation that was to last for over a century—until Henry of Bolingbroke seized the English throne from Richard II in the year 1399 and circumstances thrust Owain Glyndwr into the forefront of an Anglo-Welsh conflict.

Shakespeare best captured the essence of Owain Glyndwr when he gave him these words in his play, Henry IV:

“... At my birth

The front of heaven was full of fiery shapes,

The goats ran from the mountains, and the herds

Were strangely clamorous to frightened fields.

These signs have marked me extraordinary,

And all the courses of my life do show,

I am not in the role of common men.”

Prologue

Iolo Goch:

Humble and good-hearted was my lord Owain. He loved his wife, his children, and his home. Above all, he loved the land unto which he was born, as any true Welshman does. He wept quietly when the English scorched the crops and razed our towns, as if he had been burned and beaten himself. He smelled the smoke of fired thatch miles before anyone else ever saw the plumes lifting skyward. He sensed storms upon the wind a day before they came. When the rains arrived, he would lift his face and thank God for the gift, as those around him cursed, shivered and complained.

When I first came to his household at Sycharth, it was only as a passing guest, a bard traveling from manor to manor. Like too many, I stayed overlong. I was free and content, trading my love of song and words for my keep.

Myself—Iolo Goch, Lord of Lechrydd—I own a parcel of land which is, more or less, a weedy pile of manure on a scattering of rocks. Scant enough to live on, let alone pay English taxes. Now, I have returned to the home of my childhood—a place forgotten by all but me and one or two others—and here it is that I sit upon my wobbly stool, night after night, wondering if I’ve enough candles to finish what it is I set out to do before my weakening heart gives up the fight. My hands, though—they ache when I hold my quill. My fingers do not always do as I will them and the words come out blotched, looking like flies squashed beneath my fist. Even in the daylight my old eyes strain to see what I have written. I must stoop so low to the parchment at times that the ink smears my chin and nose.

Let me tell you, then, of my lord, his wife, and their children. I will tell you, as well, how fate taunted and beckoned to my lord and set him on a path he would rather never have known, but for which he was destined.

1

Treffgarne, Wales — 1359

On the threshold of heaven lies Wales. Rugged and remote, it is a land more suited to hunting and shepherding than planting crops or building cities; a land of sweeping moors and verdant meadows; of forests deep with shadow and bottomless lakes concealed in deeply cut valleys. Along its jagged spine running from north to south, the rocky earth thrusts upward, parting the clouds as they drift by. Rivers that begin as a trickle from melting snows grow until they are broad and sluggish with silt, finally disgorging their burden into the mouth of an angry sea. Across the water, beyond the setting sun, lies Ireland. To the east, beginning at the fertile, undulating Marches, is England, ever present and ever persistent.

In late May of the year 1359, a gathering wind marched down from the Irish Sea and collided with the Welsh shore. Battalions of marram grass held their ground while nesting terns stood guard over their clutches beneath the hammered blades. A line of thunderheads, dark as death, advanced. Daylong, storm clouds had convened over the cold, restless waters—building, growing and waiting for nightfall just as an army amasses before descending upon the enemy.

There had been no sunrise or sunset, just the slow, subtle change of hue from blackness to shades of gray and back again in a sky without sun or moon or stars.

While nature raged, inland the first drops of rain gently splattered on the roof of a manor near the little village of Treffgarne.

Owain ap Gruffydd Fychan was shoved into the world a bloody mess. His purple fists, balled tight in protest, quavered at the chill air. From between his naked gums a mighty wail issued forth and rent the heavens. In answer, the gods rumbled.

Outside the stone-clad house, daggers of rain slashed at the windows. The sky was a splendid show of terror. In the thin-soiled hills beyond Treffgarne, snowy-faced sheep ran and scattered. The hill cattle, with their sturdy frames and shaggy hides, being of a more obstinate constitution, packed themselves brisket to flank in the windbreak of a craggy cirque.

On that lightning-scoured night—a decade past the purging of the Black Death, which knew neither class nor calling, and less than a century after the exigent Edward I had thrown his stone yoke of castles about the necks of the Cymry—a life was delivered to Wales. A beginning amidst the cataclysm. And a glory, as any child, in the making.

The midwife Enid pinned the wriggling babe under an age-spotted forearm. She blotted at his cheeks with a frayed strip of linen and hoisted him up, unclothed, for his new mother to see. His legs kicked at the air with all his might.

“He has strength, ’tis certain,” she heralded as he gulped in air. Dried blood tinged the creases in her knuckles. She laid him in his cradle. “You’ll not get a wink of sleep till his belly’s filled.”

With a steady hand, Rhiannon helped her lady to bed and moved the peat brazier closer. Elen, wife of Gruffydd Fychan, who was off fighting in France, had delivered the boy straining and squatting upon the planked floor of her parents’ chamber. She had cried out not once, though the pain of birthing had been fierce enough for her to wish herself unconscious. It was only the wooden handle of a spoon, clenched hellishly between her teeth, which rescued her mind from the stony bulging in her loins as the baby had rammed his way out of her.

The old midwife dabbed her wrinkled fingers in a hornmug of water, then caked them with salt from a wooden bowl. After rubbing little Owain’s slimy skin with the paste, she wiped her hands clean and dunked a honey-smeared finger into the infant’s mouth. He sputtered and finally swallowed. Soon, his pink tongue licked at the roof of his mouth and his lips puckered into an ‘o’. She settled the boy onto his mother’s bare stomach, still bloated and tender.