Untold Stories (67 page)

Authors: Alan Bennett

I came backwards to French painting. I like Vuillard's interiors but it was Harold Gilman's I knew first so that I came to Paris via Camden Town. There is no patriotism involved but I think it's a pity that so many modern English painters are ranked a poor second to their French contemporaries. The reasons are as much commercial as artistic; their prices remain relatively modest because few Americans know much about English twentieth-century painting, though a notable exception was Vincent Price, who had several Camden Town pictures, picked up for what in international terms was a song. Leeds owes most of its splendid Camden Town pictures to the taste and foresight of Frank Rutter, who was Director here from 1912 to 1924 and who said of Gore, âHe was the most lovable man it has been my privilege to know.' In some ways the most refined painter of the group, Gore died quite young from pneumonia just when his paintings were beginning to be flooded with sun and light.

G

WEN

J

OHN

,

Portrait of Chloe

Boughton

-Leigh

, 1910â14

Gwen John was the sister of Augustus John â or perhaps one should say that Augustus was the brother of Gwen, because whereas since her death in 1939 her reputation has continued to grow, his is now rather patchy. She was the opposite of her brother in almost every respect, by nature diffident and retiring and painting with restraint and delicacy but with great strength. She was a friend of Rodin and an admirer of Whistler and a few years ago she was vividly (and bravely) portrayed on television by Anna Massey.

In her dedication and asceticism and her lack of concern for her reputation (she seldom exhibited her work) Gwen John conforms to one

notion of what an artist should be just as her more flamboyant bohemian brother conforms to another.

R

OGER

F

RY

,

Portrait of Virginia Woolf

,

c

.1910

Portrait of Nina

Hamnett, 1917

D

UNCAN

G

RANT

,

Still-Life

, 1930

Roger Fry is represented in the collection by a small and not very interesting landscape. He was more influential as an aesthetic theorist than as a painter but I've always found his portraits particularly satisfying. The portrait of Nina Hamnett which is in the University of Leeds' art collection is an excellent example.

The portrait of Virginia Woolf is on loan to the Gallery and must have been painted about 1910. The strained expression and hunched shoulders suggest that it may have been done on the verge of one of her frequent breakdowns. But she didn't like having her portrait painted so maybe that's where the tension arose.

Duncan Grant was married to Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf's sister, and this still-life was painted in 1930.

Painters seem an altogether nicer class of person than writers, though they often make good writers themselves. They're less envious of each other, less competitive and with more of a sense that they are all engaged on the same enterprise. I once met Duncan Grant when he was very old and asked him if he was envious of other painters. There was a pause, then he said, âTitian, sometimes.' It was a good remark because besides being a joke it was also a rebuke to me for being so shallow-minded.

Seeing the little boy when we were making

Portrait or Bust

laboriously spelling out the label under Barbara Hepworth's

Dual Form

then looking up at it, grinning and saying, âIt's good is that!' makes me realise that there comes a point, particularly in music and the visual arts, where one's taste stops developing â or at any rate falters. Thus in English music I never got much beyond Walton and Vaughan Williams, and in English painting, though I don't quite stop, I certainly slow down in the late 1950s and

begin to settle for what I know already. Thus I like the smoother, suppler forms of Henry Moore and dislike (or don't feel easy with) the pointy-headed figures that come later. And, unlike the little boy, don't go much for Barbara Hepworth.

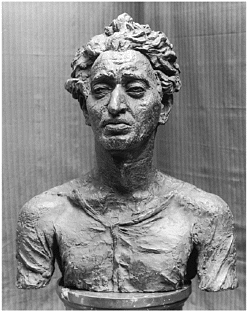

J

ACOB

K

RAMER

,

The Day of Atonement

, 1919

J

ACOB

Epstein,

Bust of Jacob Kramer

,

c

.1921

Tramps are, I suppose, an occupational hazard of art galleries, particularly these days, but I should be sorry to see them turned away, their right to look at the pictures (or not look at them) every bit as inalienable as mine.

Still, I can see they can pose problems. I wrote a television play once in which there was a scene in a provincial art gallery with a conversation between a down-to-earth attendant and a casual visitor:

VISITOR

: Now then, Neville. Not busy?

ATTENDANT

: Ay. Run off us feet. (

The gallery is empty

)

VISITOR

: I could do with your job.

ATTENDANT

: It carries its own burdens. We get that much rubbish traipsing through here I feel like a social worker. This is one of their

regular ports of call, you know. Here and the social security. Mind you, they don't come in for the pictures.

VISITOR

: No?

ATTENDANT

: No. They come in for the central heating. Genuine art lovers you can tell them a mile off. They're looking at a picture and what they're looking for are the effects of light. The brush strokes. Economy of effect. But not the lot we get. Riff-raff. Rubbish. Human flotsam. The detritus of a sick society. Shove up half a dozen Rembrandts and they'd never come near. Turn the Dimplex up three degrees and it's packed out. (

He stops another visitor

) You're not looking for the Turner?

VISITOR

2: Sorry?

ATTENDANT

: No. Beg pardon. That's generally what they all want to see. Anybody who has any idea. âWhere's the Turner?' Flaming Turner. I can't see anything in it. Looks as if it's been left out in the rain. We had Kenneth Clark in here once. Same old story. âWhere's the Turner?' I've never seen a suit like it. Tweed! It was just like silk. Then some of them come in just because we have a better class of urinal. See the Turner, use the urinal and then off. And who pays? Right. The ratepayer.

(

Afternoon Off

, 1979)

There was often a tramp in here in the late forties, hanging about the gallery or slumped over an art book in the corner of the Reference Library. Except that he wasn't a tramp; he was quite a distinguished painter, Jacob Kramer, and his bust by Epstein is one of the most powerful pieces of sculpture in the Gallery. Kramer was Jewish, his family from the Ukraine, one of many thousands of Jewish families who came to Leeds at the end of the nineteenth century. As a young man he was a Vorticist and an associate of Wyndham Lewis and William Roberts. I'd find it hard to say what Vorticism is; I think of it as the jagged school of painting, Cubism with an English slant, but both Kramer's Jewishness and his Vorticism can be seen in

his

The Day of Atonement

, which was unveiled in the Gallery in 1920 to a storm of anti-Semitic protest.

There was still a lot of anti-Semitism in Leeds even after the Second War, and I can remember Jewish boys in my school being regularly bullied, one boy in particular, Alan Harris, always coming in for it. The masters used to turn a blind eye and even collaborate, one master catching him a terrific slap across the face for very little reason. Years later when I was in Harrogate I ran across this master, now tranquilly retired, in a tea shop and as he came up to me I thought, Oh yes, you're the one who hit the Jew. Nowadays Asians have replaced the Jews in the front line, living where the Jews used to live, the difference being that nowadays we talk about prejudice, whereas in those days one never mentioned it.

Kramer himself died in 1962 indistinguishable from a lot of the tramps whom you'll see outside. Except that in 1966 Leeds College of Art was, briefly, renamed after him, so he was more respectable in death than he ever was in life.

Though the collection is particularly strong on twentieth-century British pictures there are inevitably gaps. There are only two watercolours by Eric Ravilious, for instance, one of my favourite painters, who caught the atmosphere of wartime Britain better than anyone. Though there are two paintings by Duncan Grant there's nothing of any great interest by his long-time associate, Vanessa Bell.

Another absentee is Hockney (except for several etchings), though with the glut of his paintings at Saltaire the region isn't exactly going short. Perhaps some of the ancient rivalry between Leeds and Bradford still persists. I'm sure one of his paintings would be better placed here than on the wall of some Californian millionaire.

In the documentary

Portrait or Bust

I told the story of how I was mistaken for Hockney in a tea shop in Arezzo. It continues to happen. A few months after the programme went out I was marooned in Nice airport with two or three hours to wait for a plane. Unless I'm being paid for I travel economy but my travel agent, who has an exalted view of my status, has VIP put on my tickets, a largely futile gesture which seldom ever gets me

upgraded. However, rather than sit on a hard bench for three hours I thought I'd use my notional status to wangle my way into the Club Lounge.

A stone-faced stewardess barred my way and I laboriously stated my case, whereupon she grudgingly undertook to make a telephone call. As she was phoning there was a tap on my shoulder. It was an English woman who, judging by her luggage and general demeanour, had a hereditary right to be in the Club Lounge and had been in Club Lounges from the cradle. âCould I', she said kindly, âcongratulate you on your designs for the

Rake's

Progress

?'

At which point the stewardess put the phone down and said, âNo. You can't come in here.'

The English have never been entirely comfortable with art and are happiest thinking of pictures as decor; I certainly prefer paintings in settings, feel easier with a picture in a room than when faced with it on a blank wall. Twentieth-century paintings in particular benefit from a domestic surrounding. I liked the mixture of paintings and furniture in the recent exhibition about Herbert Read, for instance, and the intimate galleries at Kettle's Yard in Cambridge carry that mixture further. The paintings can benefit too, and the shortcomings of the Bloomsbury painters become virtues when one sees their pictures as part of a comprehensive (if haphazard) decorative scheme as one does at Charleston. And of course this applies to much grander artists too. How many old master paintings, now seen in splendid isolation in galleries, were once part of rich and complex decorative and devotional schemes that we can now scarcely imagine?

Which makes me feel less frivolous five centuries later for liking to see a vase of flowers, say, beside or even in front of a painting.

The focus of this selection has been unashamedly retrospective, concentrating on the pictures I got to know in this Gallery when I was young. What my generation had then, which I think has weakened since, was a powerful sense of the city. I've mentioned that Atkinson Grimshaw's painting of Park Row reminded me of Genoa or Florence. I don't think it's fanciful to take that further and say that in the forties and fifties one

had a sense of belonging to Leeds that can't have been unlike the feelings of someone growing up in a fifteenth-century Italian city-state.

There were the arms of the city for a start. Everywhere in Leeds in those days one was confronted with the owls and the lamb in the sling and the motto â

Pro Rege et Lege

'. One could not escape those arms. They were on my schoolbooks and they were at the tram stop; they were on the market; they were over the entrance to the Central Library (where, rather battered, they still survive). At every turn there was this reminder that you were a son or daughter of the city.

Its relics persist and in unexpected places. Staying at the Metropole Hotel while we were making the TV programme on which this selection is based, I happened to go down the side of the hotel and there, for no particular reason and seemingly over the kitchen door, was the familiar coat of arms, the stamp of Leeds.

I'm sure this sense of place survives but in a different form. The West Yorkshire Playhouse will centre some people's sense of identity. Leeds United (never much of a team when I was a boy) will centre others'. And I would not be so foolish as to say things were altogether better then or worse; they were different. Of one thing, though, I am sure.

My affection for this collection began in the late 1940s and it's coupled in my memory with other formative experiences of that time, with the books I borrowed from the public library next door, for instance, or with the concerts by the Yorkshire Symphony Orchestra that I heard every Saturday night in the Town Hall. The pictures were free, the library was free and the concerts (at 6d a time) were virtually free. And I was being educated at Leeds Modern School, which was, naturally, free and in due course went off to university, at first on a scholarship from Leeds, then on one from my college, free again.