Untold Stories (65 page)

Authors: Alan Bennett

Stanley Spencer painted this lovely, blustery picture âbefore the war', as I tend to think of it, because within two years beaches like this would be cordoned off, the shore strewn with tank traps and the sea unreachable behind rolls of barbed wire. That was what the seaside was like when I first saw it, so this painting is for me a carefree vision of what holidays were like between the wars.

In 1925 Spencer had married his wife Hilda in a village not far from Southwold, but in 1937 the marriage had broken up and Spencer came back to Southwold in great distress of mind. None of this sadness finds its way into the picture, painting as much an escape for the artist as the holiday is an escape for the people in the deck-chairs.

Stanley Spencer didn't quite play the artist in the manner, say, of Augustus John; but his odd personality has tended to get in the way of his professional reputation and has somewhat diminished it, much as Lowry's did, both of them too easily caricatured as the artist as eccentric. It's a way the newspapers have of making art palatable, of showing how unpretentious we English are, but it's not much more useful or informative than a view of French art which has the painter wearing a smock and beret and living in a garret. There's no doubt that Spencer was eccentric. His cousin said that he didn't look fit to take a sheep down the street and he was a gift to magazines like

Picture Post

, one minute pottering round Cookham with his paints in a pram, the next doing his stint as a war artist in the Glasgow shipyards.

One is so used to allegory in Spencer's work that when it's absent, as it

is here, one feels a little uneasy, as if the painting is perhaps a detail from something much larger â âChrist and the Miraculous Draught of Fishes', say, with the fishing boat just off the top of the canvas. Or perhaps it's the âCalling of the Disciples', Christ skirting the shoreline off to the right with some of these determined sunbathers blissfully unaware that they're about to be enlisted among the Twelve. But Southwold is not Galilee, just a select, rather refined seaside place which retains much of its gentility today.

The towels deserve a word. I know this kind of towel from childhood, thin, ribbed, the nap long since gone, and only just big enough to do the job. It's the kind of towel, brisk, bracing and comfortless, that would have commended itself to Baden-Powell. Towels for me have always been strong indicators of class, the often smelly towel that hung behind the kitchen door when I was a child firmly putting us in our social place, a pile of thick fleecy towels in the airing cupboard signifying luxury and something that I've never quite attained. When I first went to America in 1962 the first present I sent home were some huge bath towels from Bloomingdale's, the sort of towels I'd always hankered after. Typically, my parents never put them in the airing cupboard, but left them in their cellophane wrappers, feeling they were too good to use. The other thing to be said about towels â and these towels in particular â is that when one used to go swimming as a child to the beach or, more generally, to the municipal baths, one carried the towel under one's arm in a kind of Swiss roll with one's cossy in the centre. Children don't do that now. Why? What happened and when?

Looking at the four paintings I ended up choosing, I can see that three of them have to do with my own childhood, most obviously the Stanley Spencer with its echoes of pre-war summers I was too young to remember.

Lorenzo and Isabella

is also to do with school, where I was quite late growing up, and I was always very conscious of how big some of my schoolfellows were, making the young man with the perfect leg both a bully to be avoided and also someone whose physique I would have envied. Stubbs's

Hambletonian, Rubbing

Down is childhood too, and the

feeling I always had of being shut out of sports and the expertise that went with sports. Only

The Adoration of the Kings

is unconnected with anything I recognise or remember, though it's also the most bewitching painting from a child's point of view.

This is not to say, though, that these are my âfavourite' paintings. I'd find it hard (and not very useful) to determine what my âfavourite' paintings were. Making lists of this kind â the Hundred Best Paintings, the Hundred Best Classics â is a silly game that newspapers and radio stations play. Of course, it's easier to do with music, but I'm sure that if there was a way of putting paintings into some sort of league table, radio and television would not hesitate to do so. So just as one is supposed to wait with breathless excitement to find out whether â

Vissi d'arte

' has dislodged Samuel Barber's Adagio from its position at No. 18 in the Classic Countdown, no doubt with paintings we would be expected to catch our breath on hearing that Paris Bordone has made a surprise entry at No. 47.

Who would have thought that one would one day groan at the name of Albinoni? God forbid that paintings should share such a jaded fate. Art is not a race. And there often is â and probably should be â something clandestine about it. When I was at school, art was a soft option for games and was in consequence looked down on. These days there's nothing so respectable as art, which is fine, except that it makes art somehow official.

All masterpieces are eloquent: not all of them are articulate. And of course it is, rightfully, one of the functions of art history to try and make a painting articulate: to demonstrate its virtues, inform you of its background and history and put it in its context. Some paintings have to be cajoled into speaking when they may have very little to say in words. There's not a lot to be said about the self-portraits of Rembrandt, for instance. âI am' is what they say. Or âHere I am again.' In fact, there are two voices: Rembrandt saying âI am' and the painting saying âI am.' Of the paintings I have chosen, the most eloquent and the least articulate is

Hambletonian, Rubbing Down

. The National Gallery has recently acquired Stubbs's Whistlejacket and that's another wonderfully eloquent but wholly inarticulate picture. And though there's lots to be said about both these

paintings, what can be said about a work of art can never outsay what a work of art says about itself.

Sometimes â and I don't mean to disparage art history, which I've always found fascinating â it's as if paintings were being doorstepped, art historians crowding in on them like reporters from the

Mirror

or the

Mail

, pestering some inarticulate unfortunate about âWhat they really feel', teasing out an inappropriate and inadequate response when the person interviewed would sensibly prefer to say nothing at all. And maybe, hearing what is said about them, some paintings might shrug, saying: âWell, if you say so.' The Mona Lisa's smile is the smile of art.

These notes arise out of a TV documentary

, Portrait or Bust,

which Jonathan

Stedall

and I made about Leeds City Art Gallery in December 1993 and which was first

transmitted on BBC2 in April 1994

.

Other than âThese are the paintings I like' I'm not sure I've much else of consequence to say about the actual paintings. What I did in the programme was to advertise my own ignorance in the hope that it would encourage people with similar feelings of inadequacy where art is concerned to come into the Gallery nevertheless. Leeds after all is not an intimidating collection. To begin with it's relatively small, you're not outfaced by it and anyone with two hours to spare can see most of it. Watercolours apart, it's weighted towards the twentieth century and has some of the best modern British paintings to be seen anywhere in the provinces.

The Gallery is friendly too and (not the least of its virtues) has plenty of seats, often with quite odd or eccentric characters sitting in them. This is all to the good. It bears repeating that people come into an art gallery for all sorts of reasons; some, it's true, because they like paintings, but with a lot of visitors, looking at the pictures is quite low on the list. They come in out of the rain, to keep warm maybe, or to take the weight off their feet; perhaps they're early for a meeting or they're on the look-out for a meeting and have come in hoping to pick somebody up â all of which are perfectly proper and legitimate reasons for being here. An art gallery, after all, is not unlike a park. But the hope is â the

faith

is â that the art will rub

off, be taken in out of the corner of the eye. Because the corner of the eye is a good short cut to the back of the mind.

When I was a boy I used to do my homework in the Reference Library next door, and I'd come down to the Gallery not because I wanted to look at the pictures but because I wanted a break. I got to know the pictures by accident, by osmosis almost; I just absorbed them. And I can see that it's from this experience that I derive my attitude to television, believing as I do that a lot of people switch on at random and with no definite idea of the programme they want to watch, just as they come in here at random and for a variety of reasons; but given good comedy, good drama, good documentaries, they can be diverted and elevated, just as they can be by good paintings.

My appreciation of painting is quite shallow. I find it hard to divorce appreciation from possession, so I know I like a picture only when I'm tempted to walk out with it under my raincoat. However much I like a painting I seldom hang about in front of it, but go and get a postcard instead. Art is hard on the feet. I loathe standing, and get more speedily exhausted in a gallery than anywhere else, except perhaps a second-hand bookshop.

My ideal gallery would be traversed by a narrow-gauge railway where one could be shunted into a siding in front of the pictures one likes. How Bernard Berenson could stand in front of a painting for hours at a stretch, just taking it in, beats me. Give me a postcard any day.

The first visit I paid to the Art Gallery was early in the Second World War when I was aged eight. There was very little to see in the way of art as, in the expectation of air raids, most of the city's pictures had been evacuated to a place of safety. Frantic operations of a similar kind went on all over the country in the early months of the war and famously in London, where the precious contents of the National Gallery were crated up and taken off, to end up eventually in a slate quarry in Wales, there to be hidden in caves.

Lacking metropolitan masterpieces, Leeds chose a handier refuge, Temple Newsam. I like to think the pictures were loaded onto a tram and

taken the little ride along York Road, through Halton and up that leafy incline by the municipal golf course to Temple Newsam House. It was a trip I'd done several times with my grandma. The contrast, though, was revealing: in London a get-away in the nick of time to a remote and romantic haven; in Leeds a twopenny-halfpenny tram-ride. From as early as I can remember, life â or at any rate life in Leeds â never quite came up to scratch.

But now we are in the Art Gallery sometime in 1942 and Standard 3 from Upper Armley National School has been brought into town by our teacher, Miss Timpson, to see an exhibition to do with Ark Royal Week. Miss Timpson is a thin, severe woman with grey hair in a bun and the kind of old lady's legs that seem to have gone out now, which begin at the far corners of the skirt and converge on the ankles. We have looked at the fund-raising thermometer on the Town Hall steps and now Miss Timpson has shepherded us into the back of a crowded hall in the Gallery where a choir of orphans from the Boys' Home and press-ganged into the Sea Scouts are singing and whistling âPedro the Fisherman'.

Entertainment was scarce in those early days of the war but even I knew that this performance was no crowd-puller and it's not long before the attention of Standard 3 begins to wander. Except that there's not much else to look at, just one large picture that hasn't been evacuated, because either it's too big or is of no artistic merit. Merit not really at the top of their list, two of the bolder boys in the class, Rowland Ellis and John Marston, have gone over to take a closer look.

It's a vast work, acres of paint varnished to an over-all brown, and it depicts the aftermath of some great battle, the kind of battle that's always being described in the Bible with mountains of dead and piteous and imploring wounded. Night is coming on and women wander over the field comforting the wounded and searching for their loved ones. Prominent among these is a striking figure (what my mother would have called âa big woman') â bold, scornful, with her many bangles proclaiming her a person of some consequence. She stands astride a wounded warrior, possibly her consort and certainly someone with whom she is on familiar terms,

because she has torn aside her bodice and, standing back from the prostrate figure, displays an ample breast.

Some of the boys in Standard 3 (not me) have begun to nudge and snigger. But I am thought to be a shy child (sly would be nearer the truth) so I hedge my bets, keeping one eye on Miss Timpson while stealing looks at this extraordinary canvas.

The sight of a breast so insolently displayed was, even in the hygienic context of art, not a common sight in 1942 so it was hardly surprising that Standard 3 had started to smirk. But the gallery was gloomy and the picture was gloomy too, so it was only gradually one made out what it was this brazen woman was doing with the breast, and as it became plain Standard 3's mirth turned to awe.

Seemingly without shame, the lady, who may have been Boadicea (though she also bore some resemblance to Mrs Hutchinson, the vicar's wife), was squeezing the contents of her breast into the (presumably) parched mouth of the injured warrior. Novel though this procedure was, what really staggered Standard 3 was the accuracy of her aim. The range was at least three yards. Of course she may have been all over the place before she got it right but certainly at the moment of depiction her perfect lactic parabola was dead on target.

Perhaps I was less surprised at this achievement than the others. I knew boys who could spit as accurately as that and I took this to be a possible female equivalent. I could not spit, at any rate over any distance, and had none of that copious supply of saliva that the more brutish boys seemed always to carry in readiness. I think I knew, even at the age of eight, that not being able to spit would mean not being able to do a lot of other things too (dive, throw a cricket ball, piss in public, catch the barman's eye), that not being able to spit was only the tip of an iceberg so vast that it would float beside and under me all the length of my life. However.

A hiatus before the choir struck up with Bobby Shaftoe brought us back to Miss Timpson's attention and she suddenly caught sight of her class, myself included, clustered round the picture. Now, whereas Miss Timpson would expect nothing better of boys like Rowland Ellis and

John Marston (both of whom could of course spit) than to be found sniggering at rude pictures, this had never been my role. I was not that sort of boy and here I was about to be tarred with the same prurient brush as the rest. But I was a precocious child and no sooner did I perceive the danger than I retrieved the situation.

âMiss,' I asked innocently, âis that what they mean by succouring the wounded?'

âNo, Alan,' said Miss Timpson crisply, âit is what they mean by smut. But very good. Do any of you others know the word “succour”? And what are you smirking about, Rowland Ellis, perhaps you can spell it?'

âS-U-C-K-E-R,' says Rowland Ellis proudly, and is mystified to get a clip over the ear.

âCome along, children,' says Miss Timpson. âNext door there are some ladies demonstrating how to knit sea-socks. We may pick up a few tips. And pay attention all of you, I shall want you to write a composition about this when we get back to school.'

Where that âAfter the Battle' painting is now I've no idea and nor has the Gallery. So utterly has it disappeared that I began to think I had imagined it; but my brother remembers it, several viewers remember it and the Chairman of the Cultural Services Committee, Bernard Atha, remembers it, so I'm not just romancing. Still, I suspect it's no loss to art, or even to memory, because if it did turn up it would probably seem much milder now than it seemed to our eight-year-old eyes then.

For all Miss Timpson's strictures, one of the earliest lessons a child learns in a gallery is the propriety of art, that art and antiquity make it quite proper to peep.

âIt's all right if it's art.' I was once in the Hayward Gallery at an exhibition of Indian painting,

Tantra

, and there was one panel on which a goddess, I suppose, was having everything possible done to her through every conceivable orifice by half a dozen strapping young men and enjoying it no end. Looking at this were two very proper middle-aged, middle-class ladies. Eventually one of them spoke:

âGoodness! She's a busy lady!'

W

ILLIAM

H

OLMAN

H

UNT

,

The Shadow of Death

, 1870

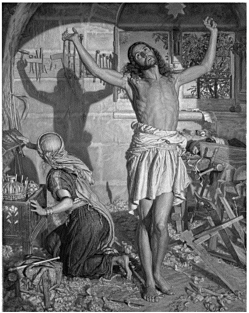

This painting is perhaps the most famous in the Gallery, Holman Hunt's

The Shadow of Death

, in which Mary sees Jesus' death prefigured. There's a larger version of the painting in Manchester but this one was the original, slightly smaller than the other versions so that Hunt could carry it around with him and make alterations as he went.

He painted the picture on location in Palestine and went to elaborate lengths to get the background and fittings right. The body of Christ belonged to one model, the head to another, who was not at all Christ-like, a notorious villain in fact and on one occasion before he painted him Hunt had to go to the local gaol and bail him out.

It's not at all plain what Jesus is supposed to be doing, apart from casting the appropriate shadow; I suppose he's meant to be stretching after a hard day's work, but it hardly looks like that. What always used to puzzle me as a child was that apart from the hair on his head Jesus (I mean not merely this Jesus, but any Jesus) never had a stitch of hair anywhere else. Never a whisper of hair on that always angular chest; God seemed to have sent his only begotten son into the world with no hair whatsoever under his arms. This rang a bell with me, though, because I was a late developer

and at fifteen was longing for puberty. So Jesus' pose here is exactly how I felt, crucified on the wall bars during PE, displaying to my much more hirsute classmates my still-unsullied armpits.

St Cyril and St Justin thought that Christ must have been (or should have been) mean and disgusting, âthe most hideous of the sons of men'. This cut no ice with the powers that be. Louis B. Mayer had nothing on the Early Fathers. They knew that someone with billing and his name above the title couldn't be a slob. So never a fat Jesus or a small Jesus even, and always a dish, though of course we must not say so.

And so serious. Scour the art galleries of the world and you will not find a picture of Jesus grinning. Jesus enjoying a joke. A God who rarely smiled, a man who never sniggered. Did he see jokes, one wonders? And were they ever on him?

There aren't many pictures of Jesus in the Gallery, which suits me as my threshold for Jesus pictures is quite low. The later they get the harder I find them to take, so that by the time we get to the nineteenth century Jesus is uncomfortably close to the only slightly sicklier versions we were given to stick in our books at Sunday School.

R

EMBRANDT VAN

R

IJN

,

Christ Returning from the Temple with His Parents

, 1654