Vermeer's Hat (13 page)

Authors: Timothy Brook

The sight of these foreigners stalled the villagers only briefly. Their eyes quickly turned to the chests and barrels floating

ashore with the survivors. They began hauling the flotsam up the beach and scavenging through the cargo. Soon enough the local

militia arrived carrying swords and arquebuses. Their duty was to keep the survivors at the site where they came ashore until

a military commander showed up to take charge. They too were interested in picking up whatever might have washed ashore from

the shipwreck. As the scavengers had beaten them to the cargo, the militiamen turned on the sodden survivors, frisking some

and strip-searching others for the silver and jewels they suspected must be hidden on them. The survivors were at first too

exhausted and frightened to do anything but comply, though a few quietly resisted. Before the militiamen had a chance to find

much, the survivors gathered together and began to walk inland.

Fearing they would be punished for failing to control the crowd, the militiamen began to throw stones and jab their spears

to make them understand that they should remain on the beach. Still the crowd of two hundred foreigners pressed forward. The

Chinese arquebusiers opened fire. One hit his target, a Dwarf Pirate, though the gunpowder charge was so weak that the ball

simply buried itself in the man’s clothing without doing any damage. The militia’s swords were more effective. A Portuguese

sailor named Francesco was stabbed and then beheaded. He was the first of the survivors to die at the hands of their captors.

Then a Macanese by the name of Miguel Xuarez was speared. A priest took Xuarez in his arms, but militiamen hauled him away

and decapitated him.

A military officer finally arrived on horseback with a small retinue. Benito Barbosa, captain of the

Guía

, hurried toward the officer to appeal for mercy for his passengers and crew, but the officer brandished his sword in a show

of intimidation and ordered his attendants to slice a piece off Barbosa’s ear, marking him as a prisoner. There would be no

negotiation; only surrender.

Then the shakedown began in earnest. Militiamen freely moved among the shipwrecked survivors, searching them and grabbing

whatever they could find. Some had managed to come ashore with a little of their wealth, and most surrendered it when accosted—but

not everyone. Ismaël, an Indian Muslim merchant from Goa, had already removed an outer garment and folded it into a parcel.

The parcel attracted the suspicious notice of a militiaman. Ismaël refused to hand it over, and in the tug of war that ensued,

the bundle slipped from his grip. Out fell six or seven silver pesos. Furious at being resisted, the militiaman ended the

tussle by cutting off Ismaël’s head. Budo, another Indian merchant from Goa, got caught in a similar struggle. One of the

militiamen guessed correctly that Budo had hidden something in his mouth. When the militiamen tried to force his mouth open,

Budo spat two rings on the ground and then kicked them into the sand to make them disappear. The disappointed militiaman feigned

indifference, but ten minutes later, slipped up behind Budo and lopped off his head, carrying it aloft as a trophy.

Others perished for reasons besides holding back their wealth. A man named Suconsaba and a Franciscan layman born near Goa

had sustained injuries during the shipwreck and were near death by the time they made it ashore. According to Adriano de las

Cortes, the Spanish Jesuit who wrote a memoir of the wreck of the

Guía

, “several of us suspected that they weren’t yet dead when the Chinese sliced off both their heads.” Masmamut Ganpti, who

may have been a slave of the ship’s owner, Gonçalo Ferreira, made it ashore without incident but got into trouble defending

his master against militiamen who tried to take his clothes. The Chinese responded by grabbing him, chopping off his hands

and feet as punishment for attacking them, then cutting off his head. Ganpti, whom Las Cortes describes as “a Moorish sailor”

and “a brave Black,” died “for no reason and without having given the Chinese the least pretext.” Another of Ferreira’s attendants

suffered the same fate, not for challenging the militiamen but for being too weak to keep up when the Chinese later force

marched the survivors inland.

The list of those drowned and murdered that morning consists of people identified as Moors, Blacks, Goans, South Asian Muslims,

Macanese, Portuguese, Spaniards, slaves, Tagals, and Japanese.

1

The casualty list is in effect a short summary of the

Guía

’s remarkably diverse passenger list. Ninety-one on board were Portuguese. Some of them were born in Macao or lived and worked

there, while others hailed from Portuguese colonies scattered around the globe, from the Canary Islands to Goa and Macao.

The only other Europeans on board were six Spaniards. A mutual agreement between Spain and Portugal restricted the ships of

one from carrying the nationals of the other, but this agreement was ignored as the need arose, especially when the people

involved were priests or Catholic laymen on mission business, as all six were. One of the six had come from as far away as

Mexico.

The Europeans made up slightly less than half the passenger list. The next largest group on the ship were sixty-nine Japanese—the

Dwarf Pirates. The Portuguese in Macao hired Japanese in significant numbers to handle their business dealings with the Chinese.

They could write Chinese characters and therefore do a better job of communicating the details of a business arrangement than

the Portuguese. Their physical features also meant that Japanese were able to move more freely among Chinese than Europeans

were. They even sometimes slipped into the interior, avoiding detection as Portuguese never could. Las Cortes knew one of

the Japanese, a Catholic priest named Miguel Matsuda. It was he who was miraculously saved when his clothing stopped an arquebus

ball. Banished by the Japanese government to the Philippines in 1614 for converting to Christianity, Matsuda trained with

Jesuit missionaries in Manila to become a priest. Now he was on his way to Macao with the plan of returning to Nagasaki on

a Portuguese ship and infiltrating his way back into Japan to spread Christian teachings. It was a dangerous mission, and

would end in Japan with Matsuda’s capture and execution.

Next most numerous, after the Japanese and the Europeans, were the group to which Ismaël and Budo belonged: thirty-four Muslim

merchants from the Portuguese colony of Goa in India, two of whom were traveling with their wives. Finally, Las Cortes mentions

in passing “Indians from around Manila” (Tagals), Moors, Blacks, and Jews, without giving numbers for these people.

The extraordinary cross section of humanity on the

Guía

’s passenger list reveals who was moving through the network of trade that Portuguese shipping sustained. Had Las Cortes not

taken the trouble to write an account of the shipwreck, and had his manuscript not been preserved in the British Library,

we would not know of the extraordinary mix of people traveling on the

Guía

. The ship’s owner and captain were Portuguese, but their passengers were a remarkably international crowd, from as far east

as Mexico to as far west as the Canary Islands. Las Cortes’s memoir thus reveals that the majority of people on what we would

identify as a “Portuguese ship” weren’t Portuguese at all, but people from literally everywhere on the globe. The

Guía

was not exceptional, for other records reveal the same thing. The last successful Portuguese trade vessel to Japan, which

sailed in 1638, consisted of ninety Portuguese and a hundred and fifty “half-castes, Negroes, and colored people,” to quote

from another such record. European ships may have dominated the sea-lanes of the seventeenth century, but Europeans were only

ever in a minority on board.

The villagers on shore were amazed by the microcosm of people from all over the globe, who gathered out of the waves. From

the villagers’ reactions, Las Cortes supposed that they “had never before seen foreigners or people from other nations.” He

guessed that “none of them had ever gone to other countries, and most had never even left their homes.” The two worlds that

encountered each other on the beach that February morning existed at opposite ends of the range of global experience available

in the seventeenth century: at one pole, those who had lived their lives entirely within their own cultural boundaries; at

the other, those who crossed those boundaries on a daily basis and mixed constantly with peoples of different origins, skin

colors, languages, and habits.

As we have no record of how these villagers reacted to the sight of Europeans, we can only fill in the gap with descriptions

from other contexts. This is one Chinese writer’s impression of Spanish merchants visiting Macao: “They have long bodies and

high noses, with cat’s eyes and beaked mouths, curly hair and red whiskers. They love doing business. When making a trade

they just hold up several fingers [to show the price], and even if the deal runs to thousands of ounces of silver they do

not bother with a contract. In every undertaking they point to heaven as their surety, and they never renege. Their clothes

are elegant and clean.” This author then does his best to assimilate these Europeans to a history with which he is familiar.

As these men were from what Chinese called the Great West (Europe), which lay beyond the Little West (India), they must be

linked to India in some way. The writer may have picked up some snippets of Christian beliefs, for he goes on to suggest that

the Spaniards must originally have been Buddhists, but that they had lost their identity and in religious matters now had

access only to corrupt doctrines.

If the white men were a curiosity, black men were a shock. “Our Blacks especially intrigued them,” writes Las Cortes. “They

never stopped being amazed to see that when they washed themselves, they did not become whiter.” (Las Cortes traveled with

a black servant. Are his own prejudices showing through?) Chinese at the time had several terms to name such people. As all

foreigners could be called “ghost” (

gui

), they were simply Black Ghosts. They were also called Kunlun Slaves, using a term coined a thousand years earlier for dark-skinned

foreigners from India, which was a land that lay beyond the Kunlun Mountains at the southwestern limit of China. Li Rihua,

the collector from Jiaxing who recognized the glass earrings his dealer was trying to pass off as ancient Chinese wares, lived

on the Yangtze Delta well to the north and had never seen a black, but he notes in his diary that they were called

luting

(a term for which the etymology is lost), and that they swam so well that fishermen used them to lure real fish into their

nets. Every fishing family in south China owns one, Li was told.

The Chinese geographer Wang Shixing provides a slightly more reliable description. He pictures black men in Macao as having

“bodies like lacquer. The only parts left white are their eyes.” He gives them a fearsome reputation. “If a slave’s master

ordered him to cut his own throat, then he would do it without thinking whether he should or not. It is in their nature to

be deadly with knives. If the master goes out and orders his slave to protect his door, then even if flood or fire should

overwhelm him, he will not budge. Should someone give the door the merest push, the slave will kill him, regardless of whether

or not theft is involved.” Wang also mentions their underwater prowess, echoing Li Rihua. “They are good at diving,” he writes,

“and can retrieve things from the water when a rope is tied around their waists.” The final thing he records about them is

their high price. “It takes fifty or sixty ounces of silver to buy one,” a price calculated to amaze his readers, since that

sum could buy fifteen head of oxen.

Wang includes this information in his encyclopedic survey of Chinese geography to document the variety of places and people

that can be found within China’s borders, which includes Macao. Li Rihua includes his data for a different purpose: to illustrate

his conviction that “within heaven and earth strange things appear from time to time; that the number of things in creation

is not fixed from the start.” Li grasped that he lived in a time when traditional categories of knowledge did not exhaust

everything that existed in the world and new categories might be needed to make sense of the novelties coming into the ken

of seventeenth-century Chinese. Unfortunately, even comically, much of this knowledge was hearsay. Li’s description of Dutchmen—“they

have red hair and black faces, and the soles of their feet are over two feet long”—presents an omnibus stereotype of a foreigner

rather than information that could be called useful knowledge.

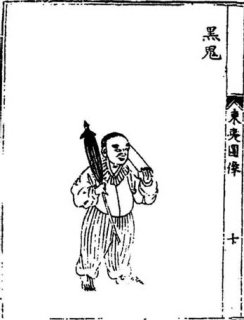

An engraving of a “black ghost,” in the terminology of the time, dressed as a Portuguese servant in Macao, from Cai Ruxian’s

Illustrated Account of the Eastern Foreigners

of 1586. Cai enjoyed the high post of provincial administration commissioner of Guangdong. This may be the earliest Chinese

representation of an African.