Vienna, 1814: How the Conquerors of Napoleon Made Love, War, and Peace at the Congress of Vienna (42 page)

Authors: David King

Tags: #Royalty, #19th Century, #Nonfiction, #History, #Europe, #Social Sciences, #Politics & Government

This was, in fact, the first time in history that states had effectively declared war on a single person. Talleyrand returned to the embassy late that night, waving a copy of the document, signed and stamped with red and black seals. His diplomatic team at Kaunitz Palace was thrilled. “I do not think,” Talleyrand concluded in his letter back to Paris, “that we could have done better here.”

O

NE PERSON INTIMATELY

affected by the news of Napoleon’s actions was, of course, his estranged wife, Marie Louise. Despite her promises to join him on Elba, she had not done so. She had instead stopped writing, or even answering his letters, and at the same time continued her love affair with General Count Neipperg.

Marie Louise had not immediately been informed of her husband’s escape. She only learned the news on Wednesday, March 8, when her son’s governess, Madame de Montesquiou, forwarded the information in a letter, before someone else told her. Marie Louise did not take it well. According to agents in the palace, the young former empress “burst into tears,” ran to her room, and cried uncontrollably, “sobbing [heard] all the way out in the anteroom.”

Only a few days before, after months of uncertainty, Marie Louise had finally been assured the Duchy of Parma as promised. She had been thrilled by the prospects of moving there with her lover, Count Neipperg, and leaving behind the bad memories of the Vienna Congress. Unfortunately, however, Napoleon’s flight was threatening to upset her life again. Wouldn’t this act of desperation be interpreted by some as breaking the treaty that guaranteed her right to Parma? Her opponents now had another excuse for handing the territory over to the Spanish Bourbons. “My poor Louise, how sorry I feel for you!” her uncle, Johan, Archduke of Austria, said. “For your sake and ours, I hope that he breaks his neck!”

With Bonaparte the outlaw on the loose and advancing closer to the French capital, it was more important than ever to keep the little Napoleon under close surveillance. The four-year-old boy playing on the parquet floors of Schönbrunn Palace was potentially, once again, heir to the French throne, and the link that could solidify Napoleon’s dynasty.

The French embassy reported hearing a rumor that someone would soon attempt to kidnap the little prince. Vienna’s police chief, Baron Hager, was also worried about this threat. Bonapartist agents were allegedly already in town, and many suspicious people had been seen in the neighborhood of the palace.

By the middle of March, Baron Hager had increased the number of guards patrolling the grounds, and he had planted more policemen in the castle, disguised as servants. In case of emergency, Hager sent a detailed description of the boy to “police stations and customs houses” in the area. Agents were told to be on the lookout for a four-year-old male, tall for his age, with blue eyes, curly blond hair, and a distinctive nose “tip-tilted with wide nostrils.” He spoke French and German, and gesticulated greatly.

On March 19, the night before Napoleon’s son’s fourth birthday, there was allegedly an attempt to kidnap him from his nursery. Rumors of this alleged abduction made their rounds, despite official denials. Soon the culprit was identified as his nurse, Madame de Montesquiou, an ardent Bonapartist. Her son Anatole, who had arrived from Paris just before, was also suspected, and promptly arrested.

It is by no means evident that either one was actually involved, and both would always proclaim their innocence. Madame de Montesquiou was fired the next day, as were many others around her. Spies also stepped up security against another Bonapartist attempt—or even, for that matter, a royalist plot—to seize the heir for their own purposes. Little Napoleon was moved out of Schönbrunn Palace and placed under tight security in the Hofburg.

Photo Insert

1. Twenty-three delegates in the negotiation room of the Austrian Chancellery. Standing, from left to right: Wellington, Lobo da Silveira, Saldanha da Gama, Löwenhielm, Noailles, Metternich, La Tour du Pin, Nesselrode, Dalberg, Razumovsky, Stewart, Clancarty, Wacken, Gentz, Humboldt, and Cathcart. Seated, from left to right: Hardenberg, Palmella, Castlereagh, Wessenberg, Labrador, Talleyrand, and Stackelberg.

2. Kings, queens, and princes, as well as rogues, renegades, adventurers, gamblers, and courtesans flocked to Vienna for the congress—“every person a novel,” the Prince de Ligne said.

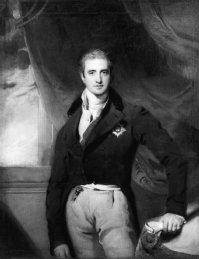

3. Austrian foreign minister and president of the Congress, Prince Metternich—handsome, flirtatious, and seemingly frivolous master of diplomacy.

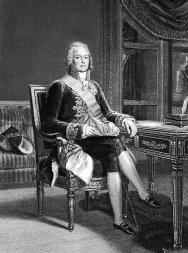

4. France’s foreign minister, the brilliant, unscrupulous “prince of diplomats,” Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand.

5. Francis I, the last Holy Roman Emperor and the first Emperor of Austria. He had once wanted a special clock that would slow down in times of pleasure and speed up in times of trial—a device that would have helped him cope with a palace full of houseguests who never seemed to agree, or leave.

6. Russian Tsar Alexander I, the foremost conqueror of Napoleon, whose sexual escapades and mystical experiences fascinated, wearied and alarmed Vienna. Alexander took offense at the Prince de Ligne’s famous quip about the “dancing congress,” believing that it was aimed primarily at him.

7. King of Prussia, Frederick William III, lived in the shadow of his famous great uncle, Frederick the Great. While he lacked his predecessor’s flair for military strategy, he certainly loved uniforms. “How do you manage to button so many buttons?” Napoleon had once teased him.