Vienna, 1814: How the Conquerors of Napoleon Made Love, War, and Peace at the Congress of Vienna (45 page)

Authors: David King

Tags: #Royalty, #19th Century, #Nonfiction, #History, #Europe, #Social Sciences, #Politics & Government

29. The tsar, the emperor, the kings, queens, and princes—along with an escort of musicians, police, and servants—embarked on a magnificent sleigh ride to Schönbrunn Palace for a banquet and ballet. They returned that evening to the Hofburg for another masked ball.

30. Once ruler of a vast continental empire, Napoleon was now emperor only of the tiny island of Elba. When the original print was held to the light, Napoleon no longer appeared alone, but surrounded by crowds of enthusiastic supporters.

31. After landing at the Golfe Juan in southern France, Napoleon camped in an olive grove outside Antibes (likely near or on the spot of today’s railway station). Napoleon had to move quickly, he knew, before news of his arrival spread, along with knowledge of just how small his army actually was.

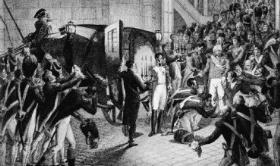

32. News of Napoleon’s flight from Elba struck Vienna, as one put it, “like a flash of lightning and thunder.” Painting captures the excitement of Napoleon’s march to Paris in March 1815.

33. On March 19, only three days after promising to die in defense of his country, King Louis XVIII left the Tuileries for northern France and then slipped across the border into Belgium.

34. Famous ball, hosted by the Duchess of Richmond, on the eve of the Battle of Waterloo, was less grand than the one celebrated in literature. It took place in a coach house or carriage workshop.

35. “Nothing except a battle lost can be half so melancholy as a battle won,” the Duke of Wellington said, surveying the scene of slaughter after the Battle of Waterloo. He hoped that he would never have to fight another battle, and he had his wish.

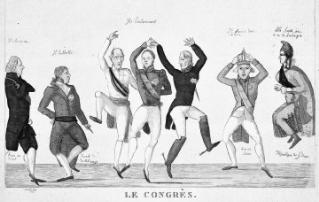

36. The Congress of Vienna, carving up Europe, trades countries like snuffboxes. The large man to the left was the king of Württemberg, the brash “monster” who stormed out of the conference in December 1814.

37. The congress dances. Britain’s Castlereagh serves as the dancing master, while Talleyrand, at the far left, observes from the sidelines no doubt awaiting his entry. The jumping figure represents the unhappy Marquis de Brignole, the delegate from Genoa, who protested the fate of his city. On the far right, the king of Saxony, who was in danger of losing his throne, clutches his crown. The “dancing congress” would be a lasting image of the Congress of Vienna.

Chapter 27

W

ITH THE

S

PRING

V

IOLETS

The fact is, France is a den of thieves and brigands, and they can only be governed by criminals like themselves.

—C

ASTLEREAGH

N

apoleon’s confidence in his success, already high, was growing as he advanced toward the French capital. With expectations of an imminent return to power, he had started appointing his new government: General Armand de Caulaincourt, his former foreign minister, was to be recalled. General Lazare Carnot, “the organizer of victory” in the Revolution, would supervise the Ministry of the Interior, and he wanted his top commander, Marshal Louis-Nicolas Davout, to head the Ministry of War. Fleury de Chaboulon, who had visited him on Elba, was also to find a place as Napoleon’s new secretary.

In contrast to Bonaparte’s spirited veterans, many in their blue coats, red epaulettes, and tall bearskin hats of the Old Guard, King Louis’s men seemed demoralized. Marshal Michel Ney—“the bravest of the brave”—swore to bring Napoleon back in an iron cage. But even he had switched sides. The Paris stock exchange continued its nosedive, the printing of newspapers ground to a halt, and government ministers fled the capital in embarrassingly disorganized retreats.

King Louis XVIII tried to rally his supporters, reaffirming his promise to confront the outlaw Bonaparte. “Can I, at the age of sixty,” the king proudly claimed to the French legislature, the Chamber of Deputies, “better end my career than by dying in defense of my country?” Many cheered the brave words, but three days later, just after midnight on March 19–20, Louis boarded a royal carriage and rumbled away from his capital.

For the sake of safety, six identical carriages left the palace at the same time, separating at the Place de la Concord in different directions. The one with the king headed north. The crown jewels, several millions in the government treasury, and another stash of funds followed in the royal caravan. The king could not be too careful. He did not want to share the fate of his older brother, Louis XVI, whose flight from Paris back in 1791 had ended disastrously with his capture, imprisonment, and eventual execution.