Vietnam (20 page)

Authors: Nigel Cawthorne

'I believe the napalming of villages is an immoral act,' he declared, holding a match to the corner of the card. 'I hope this is a significant act – so here goes'.

He lit it and was arrested by the FBI. At the end of October, he became the first American to be arraigned under a new law that made draft-card burning a federal offence with a maximum penalty of five years in jail and a $10,000 fine. The pacifist Terry Sullivan was sent to jail for a year for destroying his draft card. Millar was certainly right in one respect – it was a significant act. Draft-card burning became a regular feature of anti-war demonstrations and the nightly news. The cameras would also capture infuriated onlookers attacking the protesters or dousing the flames with water or fire extinguishers. The leading ranks of a New York march were drenched with red paint; in Chicago and Oakland, demonstrators were pelted with eggs. In Detroit marchers chanting 'Hey, hey, LBJ! How many kids did you kill today?' were drowned out by pro-war protesters singing 'The Star Spangled Banner'. When leading pacifist David Dellinger visited North Vietnam in 1966, he was denounced as a traitor.

Despite the opposition of a great many ordinary people, the protests continued. In New York and Chicago, students seized university administration buildings in protest. At New York University, 130 students and members of the faculty walked out when Defense Secretary Robert McNamara turned up to collect an honourary degree. Although attitudes towards the war often split along generation line, teachers soon began to support their students, whose leaders were calling for an end to the draft. In June 1966,

The New York Times

ran an anti-war ad signed by 6,400 academics, and on 13 November, 138 prominent Americans signed a document urging 'men of stature in the intellectual, religious, and public service communities' to withdraw their support for America's policy in Vietnam, although five days later the American National Conference of Catholic Bishops confirmed its support of US actions in Southeast Asia.

By 1967 American society was becoming increasingly divided. The anti-war movement now embraced a broad coalition of radical groups. The anti-war intellectuals, notably Dr Spock, the novelist Norman Mailer, and MIT linguistics professor Noam Chomsky, had been addressing 'teach-ins' at colleges organised by Students for a Democratic Society. This caused problems among pro-war parents. One mother asked for her son's college scholarship to be revoked after he was shown Vietcong propaganda movies at school. But in 1967, these leading anti-war activists began to appear on television. Even on Johnny Carson's

Tonight

show, guests openly expressed anti-war sentiments, though Carson kept his views to himself.

Television played a key role in the war. Vietnam was the first televised war. As well as giving the protesters voice, it showed vivid scenes of the fighting every evening on the nightly news. Unlike wars before and since, in Vietnam the military had no chance to restrict TV crews' access to the war zone or censor their coverage. American viewers could witness every mistake and reverse. They could see grunts zippoing hootches, or Americans bombing and shelling Vietnamese homes in Saigon after the Tet Offensive. The American custom of shipping their dead home in body bags also damaged domestic morale. The British, by contrast, like to bury their dead on the battlefield – it is considered an honour so 'that there's some corner of a foreign field that is forever England'. In America, consignments of coffins arriving at airports and endless hometown funerals made their losses very public.

In January 1967, the US Court of Appeal ruled unanimously that local draft boards could not punish anti-war protesters by reclassifying them 1-A. On 31 January 2,000 clergymen marched on Washington, DC, demanding an end to the bombing of North Vietnam. In February, there was a three-day 'Fast for Peace' by Christians and Jews and, in March, Martin Luther King told 5,000 demonstrators in Chicago that the war in Vietnam was a 'blasphemy against all that America stands for'.

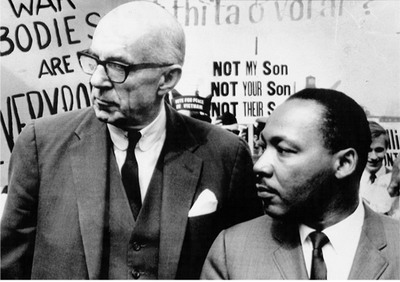

Dr Benjamin Spock and Dr Martin Luther King lead a 3000-strong anti-war demonstration in Chicago, 25 March 1967.

On the weekend of 15–16 April 1967, 125,000 anti-war demonstrators gathered in New York, with another 5,000 in San Francisco as part of the 'Spring Mobilisation to End the War in Vietnam'. At a demonstration in Central Park, protesters in bizarre costumes carried placards that said: 'Draft beer, not boys' and 'I don't give a damn for Uncle Sam'. One African-American held a sign that pointed out: 'No Vietcong ever called me Nigger'. Dr King delivered a statement to the United Nations, accusing the US of violating its charter. However, protesters outside the UN building still had to be protected from pro-war demonstrators by mounted policemen. These protests were condemned by the House Un-American Activities Committee, who claimed that they were inspired by Communists. Their report was, in turn, condemned by Reverend James L. Bevel, a prominent anti-war cleric and King's adviser. Senator Robert Kennedy spoke out defending 'the right to criticise and dissent' and said that those donating blood to North Vietnam were maintaining 'the oldest tradition of this country'.

The anti-war protests were already having an effect. Nixon, who was criticising the Johnson administration for taking a soft line on Vietnam, claimed on a visit to Saigon that 'this apparent division at home' was 'prolonging the war'. Westmoreland said that anti-war activity in the US 'gives him [the enemy] hope that he can win politically that which he cannot accomplish militarily'. He went on to say that his troops in Vietnam were 'dismayed, and so am I, by recent unpatriotic acts at home'. And on a visit home in April 1967, he addressed Congress in an attempt to stiffen the resolve of the American people.

'Backed at home by resolve, confidence, patience, we will prevail in Vietnam over the Communist aggressor,' he said. Johnson agreed that 'protest will not produce surrender'. But on 27 September 1967, an advertisement appeared in the press, signed by 300 influential Americans, asking for funds to support an organisation helping young men dodge the draft. Johnson could not help but acknowledge that the war was becoming unpopular. Speaking in Washington on 7 October 1967, he said that he was not going to court cheap popularity 'by renouncing the struggle in Vietnam or escalating it to the red line of danger'.

Former President Dwight D. Eisenhower said, 'America doesn't have to apologise for her part in the war. She can be proud of it'. But the youth of America were far from proud of what was being done in their name. On 21 October 1967, some 50,000 demonstrators marched on the Pentagon. It was the biggest anti-war demonstration to date. In a televised showdown, they faced 10,000 US Army troops and National Guardsmen drawn up to defend the building. The soldiers had rifles though no ammunition, but were authorised to break up the demonstration by force. At first the confrontation was peaceful. Demonstrators came up to the soldiers and poked flowers down the barrels of their guns, while another group attempted to mystically levitate the building. But as night drew on it was broken up with considerable brutality.

The March on the Pentagon was the idea of the National Mobilisation Committee to End the War in Vietnam (MOBE), formed in 1966 to coordinate anti-war demonstrations. In the spring of 1967, they decided to hold a protest in Washington, DC, aiming to attract one million protesters. But MOBE director James Bevel fell ill and their chairman David Dellinger was abroad, so former Berkeley Vietnam Day Committee organiser Jerry Rubin was called in. However, he had changed since his VDC days and MOBE members were shocked to find he was now into hallucinogenic drugs and Native American religion. He also asserted the five-sided pentagon was a symbol of evil that had to be 'exorcised'. Nevertheless, on 26 August 1967, MOBE agreed to hold a protest at the Pentagon.

Two days later, at a press conference in New York, Rubin announced that protesters would shut down the Pentagon by blocking its entrances and halls on 21–22 October. This was perfectly feasible as, in those, days there were no security checks and anyone could walk into the Pentagon. Then Rubin's sidekick, former civil-rights activist Abbie Hoffman, told the nation that they were going to 'raise the Pentagon 300 feet in the air'. Dellinger urged protesters to attack other federal buildings.

'There will be no government building unattacked,' he said.

Many of MOBE's more conservative supporters were put off by these outspoken tactics, but Dellinger said that it marked the anti-war movement's transition 'from protest to resistance'.

The administration was frightened that the demonstration might turn violent and threatened to ban it unless MOBE leaders renounced their threat of civil disobedience. This would prove counterproductive, as the threat of a ban was regarded as political repression and many disparate groups rallied to MOBE's cause. The administration was forced to let the demonstration go ahead, but confined the route to narrow side roads and the Pentagon's parking lot, over a thousand feet from the building.

On 20 October protesters began pouring into Washington. Washington reacted as if it were facing a full-scale revolution. Access to all government buildings was restricted. The speaker ordered the House of Representatives locked and Congress passed a bill to protect the Capitol from armed intruders. Wire barriers were erected down Pennsylvania Avenue outside the White House, with tours being limited to VIPs. The president's wife, Lady Bird Johnson wrote in her diary that it was like being in a state of siege.

Six thousand soldiers were at hand. Shortly after dark on 20 October, troops in full kit, carrying rifles, C-rations and teargas, moved into the Pentagon. Jeeps and trucks of the First Army sat bumper to bumper in four underground tunnels, the lead vehicles draped with beige cloths to conceal their identity. Across the country another 20,000 troops were put on alert in case there was an uprising in the ghettos. Two thousand National Servicemen were mobilised to support Washington's 2,000 policemen, 800 of whom were protecting the Capitol. More 'special policemen' were hidden in the Executive Office Building. Blankets were concealed along the route of the march to snuff out anyone who might try and set themselves on fire. However, arrests were to be kept to a minimum, in order to avoid attracting more national and international attention to the protest.

On the morning of the 21st, over 100,000 gathered at the Lincoln Memorial. Placard slogans ranged from 'Negotiate' to 'Where Is Oswald When We Need Him?' – a reference to Lee Harvey Oswald, the accused assassin of President Kennedy. Then, with helicopters buzzing overhead, they headed off towards Arlington Bridge. Meanwhile, with a secret service helicopter hovering over the White House, President Johnson invited journalists to watch him working in the Rose Garden. He made a show of being unconcerned, believing the demonstration would be broken up too late to get much coverage in the Sunday papers.

Once the march reached the other side of the bridge, a group carrying a Vietcong flag peeled off and made a dash through the woods to the Pentagon, where they were surrounded by MPs and US Marshals. Another group tore down a barrier and got into the building, only to be beaten up by waiting troops.

When the main group reached the building they appealed to the troops guarding it to come and join them. A protester from Berkeley put flowers down the barrels of their guns. Abbie Hoffman and his wife, high on acid and wearing tall Uncle Sam hats, made love in front of the troops. Others followed suit shouting, 'We'd rather f*** than fight'.

Young women clawed at the zippers of the soldiers and offered to take them into the woods if they changed sides. One reportedly accepted the offer, but was bundled away by officers. More than 200 draft cards were burnt.

Sharpshooters lined the Pentagon roof and, watching from their office windows, were Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who by that time was regularly seen weeping in his office, and defence analyst Daniel Ellsberg, the man who leaked the 'Pentagon Papers'. Many Pentagon officials were unnerved by the situation, knowing their own children were among the demonstrators.

As dusk fell, most protesters began to drift away, but around 400 stayed. Shortly before midnight, a V-shaped phalanx of troops came out kicking and clubbing the protesters. Women were beaten in the face with rifle butts. Rubin urged the protesters to fight back and they began setting fire to pieces of wood and hurling them at the Marshals. Though more moderate voices spoke up and some protesters withdrew, others who had been camping out in the woods returned. The following day some 2,000 protesters were still besieging the Pentagon. Rioting continued sporadically for two days. TV viewers saw coverage of the 82nd Airborne's action on the Potomac interspersed with the 1st Air Cavalry's action in Vietnam on the nightly news.

In all 683 people were arrested, including two UPI reporters and the novelist Norman Mailer who immortalised the event in his book

The Armies of the Night

. Fifty-one were given jail terms ranging up to 35 days and fined $8,000 in all. There were numerous injuries but no deaths. Mailer's presence in the anti-war movement was important. He was no pacifist and had come to prominence with his first novel

The Naked and the Dead

, based on his experiences in the Pacific, hailed as one of the finest novels to come out of World War II. With the death of Ernest Hemingway in 1961, Mailer had inherited his macho mantle. But instead of celebrating this war he became deeply pessimistic about it. In 1967, he published the novel

Why Are We in Vietnam?

. Strangely, it is not set in Vietnam at all. The action takes place on a hunting trip in Alaska. However, the book explores men's quest to prove their masculinity and the relish that human beings take in killing – issues that seemed to be possessing America as a nation in its attitude to the war at the time.