Village Centenary

Authors: Miss Read

Miss Read

Illustrated by J. S. Goodall

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

Boston New York

First Houghton Mifflin paperback edition 2001

Copyright © 1980 by Miss Read

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from

this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Visit our Web site:

www.houghtonmifflinbooks.com.

Library of Congress Catalogtng-In-Publication Data

Read, Miss.

Village centenary.

I. Title.

PR

6069.

A

42

V

5 1981 823'.914 81-6300

ISBN

0-618-12703-8

Printed in the United States of America

EB

10 9 8 7 6 5

To

Mary and Victor

with love

It was Miss Clare who first pointed out that Fairacre School was one hundred years old.

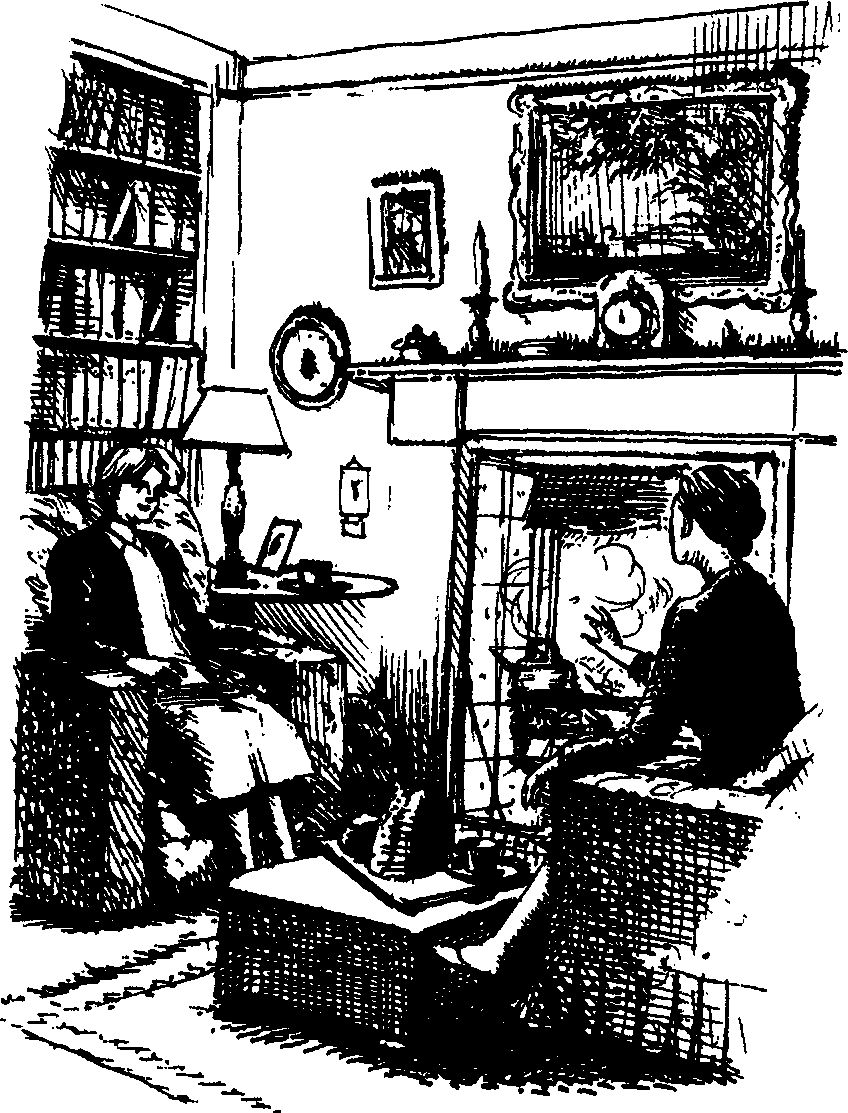

It was a bleak Saturday afternoon, and we were enjoying hot buttered toast by the schoolhouse fire. Outside, the playground, and beyond that the fields and distant downs, gleamed dully white in the fading light. It had snowed every day since term started over a week ago, and from the look of the leaden skies, more was to come.

The leafless trees stood stark and black in the still air. Distant hedges smudged the whiteness, and a flock of homing rooks fluttered by like flakes of blackened paper.

It looked like a sketch in charcoal from the schoolhouse window. The only spot of colour in this black and white world came from the crimson glow of a bonfire in Mr Roberts's field next to the school. During the day the flames had leapt and danced while a haze of blue smoke wavered about them, but now that the men were homeward bound the fire was dying down - the one warm, glowing thing to be seen.

Indoors we were snug enough. Between us, in front of the log fire, stood the tea tray, the cups steaming fragrantly with China tea. The lamp glowed from the bookshelf behind Miss Clare's white head, making a halo of her silver hair. Miss Clare knows Fairacre School well, for she was both pupil and teacher there for many years, and was serving

as infants' teacher when I was first appointed as headmistress, until ill health caused her retirement.

Since she was six years of age she has lived in a small cottage in the next village of Beech Green - a cottage thatched by her father, and later by the young man who inherited her father's thatching tools. She lives alone in her old age. Her childhood friend, Emily Davis, shared the cottage with her until she died some time ago, and although Dolly Clare has adapted herself to solitary living with the courage and sweetness of disposition which has characterised all her life, nevertheless, I know that at times she is lonely and appreciates a few hours in someone else's company.

I suspect that the winter is a particularly solitary time for her. In the summer, she busies herself in the cottage garden, or makes the jams and jellies for which she is renowned. Friends from neighbouring villages or from the market town of Caxley drive out to visit her, enjoying a country outing. There are more calls around Christmas, with visitors bearing gifts and good wishes. But after Christmas, with excitement past and dark evenings, icy roads, and the blight of winter ailments all taking their toll, the long dark nights hang heavily and I try to fetch Dolly occasionally to share my hearth and modest repast, and to give me the inestimable pleasure of her quiet and wise companionship.

'My mother used to say,' said Miss Clare, stirring her tea, 'that once January was over you could look forward to having a walk after tea in daylight.'

'That really is something to look forward to,' I agreed. 'Let's hope we get an early spring. The children haven't had one playtime outside yet, and they are all suffering from the January blues - a horrid disease.'

'It was always so. I expect the first headmistress said much the same thing a hundred years ago. By the way, are you proposing to celebrate the centenary?'

'To be honest, I hadn't realised we were a hundred until you pointed out the date over the door just now. I suppose we'll have to do something to mark such an occasion.'

'We had quite a bustle, I remember, when we were fifty years old in the thirties,' said Miss Clare. 'Mind you, it made a lot of talk. Some people wanted to take the children to London for the day. The Wembley Exhibition some years before had been a great success with the village people, all bowling up in charabancs, and having a marvellous time.'

'Did you go?'

'Indeed I did, and I think the statue of the dear Prince of Wales in butter was the thing that impressed me most!'

'Were there any other suggestions?'

'Oh, plenty! You know what village decisions are as well as I do. There were weeks of discussion -1 was going to say

wrangling -

and dozens of ideas, but in the end we just celebrated with a marvellous tea party, and really everyone was happy.'

'I can see I shall have to start thinking about it. You'll have to let me know what some of those ideas were. One thing sparks off another when it comes to sharing suggestions.'

'No doubt you'll find some help in the log book,' said Miss Clare. 'There were lots of meetings held in the school, and I expect some of the decisions were recorded. And I'll certainly rack my brains for possible ideas. It will be fun to have something to look forward to.'

Her eyes sparkled at the thought, and I could not help feeling that my old friend was more enthusiastic about the village centenary than I was at the moment. No doubt though, I told myself bracingly, once I got down to it I should feel quite as excited about the celebration of our historic century as did my companion.

Later that evening I drove Miss Clare through white lanes to Beech Green. The roof of her cottage was topped with snow. The moon was rising and the sky was pricked with stars. Already the frost had formed, and we crunched our way up to the front door.

We made our farewells and before I returned to the car I turned to her. 'Let's make another date for the first of February,' I said. 'I'll fetch you after school, and we'll have that walk in daylight after tea, as your mother said.'

'That would be lovely,' agreed Miss Clare, and I left her at her door, the light from the cottage streaming out upon the winter garden, and our breath making little clouds before us as we waved farewell.

As so often happens when one's attention is drawn to something, references to the coining centenary came thick and fast.

Mr Willet, who is our school caretaker, church sexton, general odd job man for the village, producer of hundreds of plants for cottage gardens, as well as chief organiser of our village functions, raised the matter one slippery morning when I was approaching the school across the treacherous playground with considerable caution.

'What you needs,' said Mr Willet, holding out a horny hand to steady me, 'is a stout pair of socks over your shoes. No need to teeter along like a cat on hot bricks if you've got summat to foil the ice. Socks is the answer. It's a good tip, miss.'

I promised to remember.

'We doin' anything about us bein' a hundred this year?' he asked.

'I expect so.'

'Well, it ought to be done proper. Stands to reason, us should have a fitting sort of celebration. A hundred's a hundred. Fairacre'll expect summat good.'

I said that I would start thinking about it, and passed through the school door, almost colliding with Mrs Pringle who was advancing with a large wastepaper basket clutched to her cardigan.

Mrs Pringle is our school cleaner, a martyr to unspecified ailments in her leg, particularly severe when asked to undertake extra work, and a thorn in my flesh. While it is always a pleasure to encounter Mr Willet, to come face to face with Mrs Pringle calls for courage, patience and a bridling of one's tongue. Quite often, when my patience is exhausted, as Herr Hitler was wont to say, we have a sharp argument. Mrs Pringle is invariably the victor in these combats as she is quicker-witted, better-prepared and, I like to think, more intrinsically malevolent than I am.

However, she is an excellent worker, and if one can turn a deaf ear to the accompanying grumbles the results of her labours are splendid. I doubt if any other school in the county has such jet-black tortoise stoves, burnished to a satin finish with blacklead and elbow grease. Woe betide any child who is foolhardy enough to sully their perfection, particularly when they have been 'done up for the summer'. In that term, no matter how low the mercury in the thermometer drops, the stoves remain inviolate, and instead we don our cardigans philosophically.

Once a week she switches her attention to my house across the playground. I can't think that I am really much more slatternly than the majority of working women, but Mrs Pringle soon makes me think so. The odd crumb on the carpet, the splash of grease on the kitchen stove, or a day's dust on the mantelpiece, are seen instantly by Mrs Pringle's eagle eye and magnified tenfold. The day that she discovered a small crust of mouldy bread '

behind,

not even in the bread bin' was a red-letter day for the lady, and I have never been allowed to forget it. When Mrs Pringle tells me that she intends 'to bottom the sitting room', I make hasty plans to be away from home for the allotted time. I prefer to be absent when she finds the assorted objects which have hidden themselves at the sides of the armchair cushions. Life is quite complicated enough for a village schoolmistress without seeking further confrontations.

On this particular occasion, Mrs Pringle put the wastepaper basket on the floor and supported herself on her upturned broom. She looked a little like Britannia with her trident, but less elegant.

'Mr Willet tells me there's a lot of talk about us getting to the century. What, if anything, are we doing about it?'

'Oh, something, I hope,' I said airily. 'But of course it will need some thought. I shall have to have a word with the vicar, and the managers. And Miss Briggs,' I added, as an afterthought.

'Humph!' grunted Mrs Pringle. 'A fat lot of

use she'll

be!'

I was inclined to agree, but could not countenance our school cleaner criticising my new infants' teacher, straight from college and trailing clouds of educational theories which were enough to curdle one's blood. She had only been with me since the beginning of term, and I sincerely hoped that she would soon settle down and do a little plain teaching instead of what she was pleased to call 'pastoral counselling'.