Village Centenary (3 page)

Authors: Miss Read

That evening my old friend Amy rang me. We first met at college, many years ago, and the friendship has survived separation, a war, Amy's marriage and the considerable differences in our views and temperaments.

Amy is all the things I should like to be - elegant, charming, good-looking, intelligent, rich and much travelled. I can truthfully say that! do not envy her married state, for 1 am perfectly content with my single one, and in any case James, although a witty and attractive man, is hopelessly susceptible and seems to fall in love at the drop of a hat, which Amy must find tiresome, to say the least of it.

'Come and have some supper,' I invited when she proposed to visit me one evening in the near future.

'Love to, but I must warn you that I'm slimming.'

'Not

again!

' I exclaimed.

'That would have been better left unsaid.'

'Sorry! But honestly, Amy, you are as thin as a rail now. Why bother?'

'My scales which, like the camera, never lie, tell me that I have put on three-quarters of a stone since November.'

'I can't believe it.'

'It's true though. So don't offer me all those lovely things on toast that you usually do. Bread is

out.

'

'What else?'

'Oh, the usual, you know. Starch, sugar, fat, alcohol, and the rest.'

'Is there anything left?'

Amy giggled.

'Well, lettuce is a real treat, and occasionally a

small

orange, and I can have eggs and fish and lean meat, in moderation.'

'The whole thing sounds too damn moderate for me. What would you say to pork chops, roast potatoes and cauliflower with white sauce, followed by chocolate mousse and cream?'

'Don't be disgusting!' said Amy. 'I'm drooling already, but a nice slice of Ryvita and half an apple would be just the thing.'

'I'll join you in the pauper's repast,' I promised nobly, and rang off.

I remembered my promise to Miss Clare and brought her over to tea on the first of the month.

A gentle thaw had set in and the snow had almost vanished. It tended to turn foggy at night and the roads were still filthy, with little rivulets running at the sides, but it was good to have milder weather during the daytime, and a great relief to let the children run in the playground at break. Under the garden hedge a few brave snowdrops showed. I had picked a bunch for the tea table, the purity of the white flowers contrasting with the dark mottled leaves of the ivy with which 1 had encircled them.

1 was glad that 1 was not slimming like poor Amy, as we munched our way through anchovy toast and sponge cake. After school I am always ravenous, and how people can bear to go without afternoon tea, and all the delightful ingredients which make it so pleasant, I do not understand.

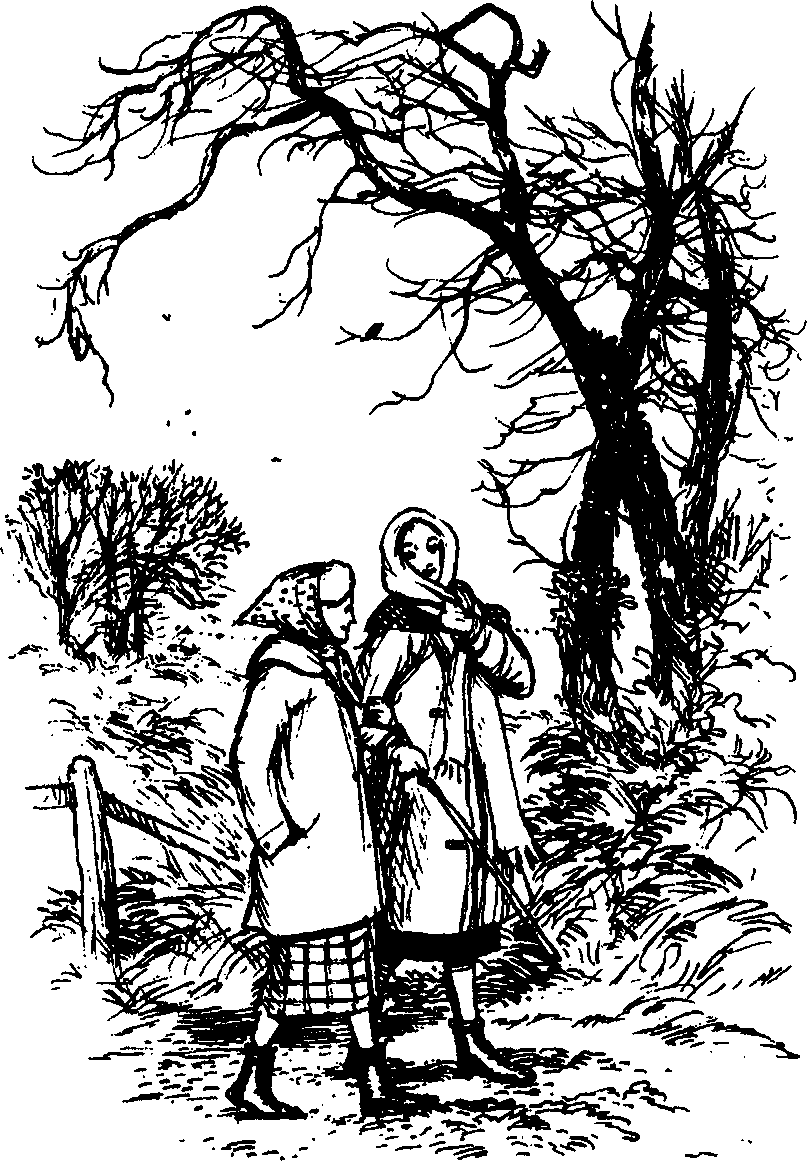

When we had cleared away, we set out on the first after-tea walk of the year. A few early celandines showed their shield-shaped leaves on the banks at the side of the lane, and it was wonderful to see the green grass again after weeks of depressing whiteness.

A lark sang bravely above, and blackbirds and thrushes fluttered among the bare hedges, scattering the pollen from the hazel catkins that nodded in the light breeze. In the paddock near Mr Roberts's farmhouse, sixty or seventy

ewes, heavily in lamb, grazed ponderously upon the newly disclosed grass. There was a wonderful feeling of new life in the air despite the naked trees, the bare ploughed fields and the miry lane we walked.

'I know most people dislike the month of February,' said Miss Clare, as we returned, 'but I always welcome it. With the shortest day well behind us, and the first whiff of spring about, I begin to feel hopeful again.'

'Your mother was quite right,' I told her. 'Everyone should have an after-tea walk on February the first. It's the finest antidote to the January blues I've come across.'

Dolly Clare laughed, and slipped her frail arm through mine. It was sharply borne in upon me how light and thin she had become during the last few years. Her bones must be as brittle as a bird's. Would my old friend survive to see the next spring? Would we share another first-of-February celebratory walk?

I hoped with all my heart that we might.

On the following Friday, I dutifully made my way to the vicarage. 1 had not heard any more about the Caxley Spring Festival which the vicar had mentioned, and wondered exactly how our small downland village, some miles from the market town, would become involved.

There were about twenty people in the Partridges' drawing room, and only two were strangers to me. Diana Hale, wife of a retired schoolmaster, was there. Their house, Tyler's Row, once four shabby cottages, is one of the show places of our village, and she and her husband are tireless in their good works.

I was pleasantly surprised, too, to see Miriam Quinn who came to live in Fairacre a few years ago. She is a most efficient secretary to a businessman in Caxley, likes a quiet life, and is somewhat reserved.

Like most newcomers to a village, I know that Miss Quinn was approached by most of the village organisations when she first took up residence at Holly Lodge on the outskirts of Fairacre, for her qualities of hard work and intelligence had gone before her and everyone said, as I find to my cost as a spinster, that a single woman must have time on her hands and enjoy a nice bit of company. Holly Lodge is the home of Joan Benson, a sprightly widow, and she and her lodger seem very happy together. Joan was not at the meeting, and I wondered how it was that Miriam Quinn had been coralled with the rest of us.

It was soon made clear. The vicar, who was acting as chairman, introduced the two strangers as the organisers of the Festival in Caxley, and Miss Quinn as Fairacre's representative.

We all sat back, sherry in hand, to listen obediently.

The Arts in Caxley, one of the strangers told us with some severity, were sadly neglected, and the proposed Festival was to bring them to the notice of Caxley's citizens and those who lived nearby. Let him add, he said (and who were we to stop him?), that he was not accusing Caxley people of

Philistinism

or

Cruelty to Creative Artists,

but merely of

Ignorance

and

Apathy.

There was a great fund of natural talent in Caxley - and its surrounds, he put in hastily - and there would be two plays by local playwrights put on at the Corn Exchange, several concerts at the parish church, and exhibitions of painting, embroidery and other crafts at various large buildings in the town, and outside.

'What happens to the money?' Mr Roberts, our local farmer, asked bluntly. Farmers are noted for their realistic approach to life, and ours is no exception.

The speaker looked a little surprised by the interjection of such a materialistic enquiry in the midst of his eulogy about Caxley's artistic aspirations, but rallied bravely.

'I was just coming to that. Any profits will go to three local charities so that a great many people will benefit. They are named in the leaflets which we are distributing at this meeting.'

Mr Roberts grunted in acknowledgement, and the speaker resumed his talk. Miriam Quinn's involvement was then revealed, and she gave a sensible description of her part in the Festival.

'I'm really here to get suggestions,' she said. 'One way of helping, particularly for us in the country, is by opening our gardens. The vicar has already offered to have his open, and so has Mr Mawne. We can arrange a date to suit us all, and in May, when the Festival takes place, our gardens here are at their best.'

'What about the schoolchildren having a maypole? Dancing and singing and all that?' called out someone, well hidden from me.

Miriam Quinn looked at me hopefully.

'I'll think about it,' I said circumspectly. What with the centenary, and the skylight waiting to be repaired, I had some reservations about a May Day celebration as well.

'Beech Green had a street fair once,' said somebody.

'And only once,' said her neighbour. 'The traffic was something awful when Mr Miller's tractor broke down where the road narrows.'

The vicar, adept at handling situations like this, suggested that any ideas might be given to Miss Quinn at the end of the meeting. He was quite sure, he added, that she would receive every possible support from Fairacre in the part that the village would play in this excellent enterprise.

Were there any more questions?

At this, as always, silence fell upon the gathering. Sherry glasses were refilled, the guests circulated again, and we all knew, as we chattered of everything under the sun bar the matter in hand, that the Caxley Spring Festival would get plenty of attention once the meeting had dispersed.

Amy paid her visit to me one evening when the wind was scouring the downs, whistling through keyholes and making the schoolhouse shudder beneath its onslaughts.

Out in the garden the bare branches tossed up and down, and dead leaves flurried hither and thither across the grass. Overhead the rooks had battled their way home at dusk, finding it difficult to keep on course.

But my fire burned brightly in the roaring draught and Tibby, on her back, presented her stomach to the warmth, paws above her head. We were pretty snug within, whatever the weather did outside.

Amy arrived in a new suede coat of dark brown and some elegant shoes that I had not seen before. She held a bowl of pink hyacinths in her hands.

'Coals to Newcastle, I expect. I know you do well with bulbs.'

'Not a bit of it! Mine are over, and you couldn't have brought anything more welcome, Amy dear. Come in, out of this vile wind.'

She divested herself of the beautiful coat, and exclaimed with pleasure at the fire.

'I've been trying to do without one. After all, the central hearing should really be enough - heaven knows it costs a small fortune to run - but there's something rather

soulless

about the electric fire which I'm forced to put on for an hour or two, now and then.'

'Well, you know me, Amy. I light a fire at the drop of a hat. I can always console myself with the thought that I have no central heating to make me feel guilty.'

'I've felt the cold far more this winter,' said Amy, stroking Tibby's stomach. 'Whether it's

anno domini

or just this slimming business, I can't tell. A bit of each, I expect.'

'How's the poundage going?'

'Much too slowly. If only I habitually drank gallons of beer, or ate pounds of chocolate, I should find it quite easy to cut down the calories, but I eat like a bird.'

'Not worms, I hope.'

'Don't be facetious, dear. You know what I mean. I'm heartily sick of salad and cold meat.'

'Well, that's what you've got tonight. Unless you'd rather have a boiled egg.'

'Either would be delicious,' said Amy, lying bravely. 'Do you know, as a child, I refused to eat salad, particularly tomatoes. '

'My

bête noir

was beetroot,' I recalled. 'Now I love it, and coffee. I didn't touch it until we went to college. I'm sure tastes change as one goes through life.'

'They certainly do. But perhaps it's simply our aging digestive systems, do you think? I used to adore potted shrimps, but these days they go down like greased nails, and 1 have terrible indigestion.'

'We could have a nice bowl of thin gruel on our laps here,' I remarked, 'if you feel in such an advanced state of decay.'

'Not likely!' said Amy. 'Besides, gruel is fattening.'

'Who was it said that anything one enjoys turns out to be fattening or immoral?'

'No idea, but he knew what he was talking about,' said Amy with feeling.

Over our frugal repast, the conversation turned to Caxley's Festival. I told Amy about Miss Quinn's part in it and our dearth of suggestions in Fairacre.

'Well, in an expansive moment I agreed to have a poetry reading in my house. Do you think anyone will come?'

'The poets will, presumably.'

'That's what I'm afraid of. I mean, shall I be stuck with half a dozen sensitive types, possibly all jealous of each other and with no audience to listen to them? How can I be sure we get a nice, kind, attentive crowd?'

'They'll come,' I assured her. 'Lots of people will simply come to see your house and garden, poets or no poets. Others will be culture-vultures, and game to listen to anything in the cause of Art, and others will feel they can't waste the ticket.'

'And there are bound to be the poets' relations,' agreed Amy, looking more hopeful. 'I wonder if we could organise a group from the evening classes in Caxley? You know the sort doing English Literature? The Beowulf bunch, for instance.'

'"Weave we the warp. The woof is wub" sort of thing, you mean? I don't see why not. English Literature classes should swell the audience nicely, and if you're short, I'll come and sit in the front row.'

'I'm counting on you, anyway,' said Amy, selecting a large stick of celery, 'to pass round the sausage rolls.'

'You'll need something far more spiritual than sausage rolls,' I told her. 'You'll have to have nectar and ambrosia, and lots of "beaded bubbles winking at the brim" for a poetry evening.'

'We'll have lashings of the latter,' promised Amy, and crunched into the celery.