Vodka Politics (51 page)

Authors: Mark Lawrence Schrad

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Europe, #General

Sakharov was long aware of the pervasive liquor problem. His

Memoirs

describe working at a munitions factory during World War II, recalling “with horror the day a roommate of mine came back from his shift after drinking a cupful of the methyl alcohol used in the plant. He became delirious and went berserk. Half an hour later, he was taken away in an ambulance, and we never saw him again.”

15

In addition to the more-or-less conventional stories about rewarding workmen with drink or drunken hotel brawls, he also explained how the prodigious academics involved in the Soviet atomic bomb project gave the straight-laced

Sakharov lessons in drinking pure 100 percent alcohol. He described how in the 1960s government procurement officers flew in helicopter loads of vodka to swindle Siberian trappers hunting in the rugged north. “After a few days the trappers and their parents, wives, and children would all be drunk, and the helicopter would fly off with furs for export.”

16

Following the 1982 death of Leonid Brezhnev, Sakharov straightforwardly condemned Soviet vodka politics.

Drunkenness is our great national tragedy; it makes family life a hell, turns skilled workers into goldbricks, and is at the root of a multitude of crimes. The rise in drunkenness is a reflection of social crisis and evidence of our government’s unwillingness and inability to take on the problem of alcoholism. More recently, cheap fortified wines have become the favored means of turning people into drunkards and siphoning off surplus rubles.

17

It is worth stepping back for a moment to appreciate the bigger picture here. Despite deep philosophical differences between Sakharov and Solzhenitsyn, these two greatest dissidents of the age were both teetotalers.

18

Neither feared confrontation with General Secretary Brezhnev, who—like all the heirs of Stalin—was a drop-dead alcoholic. In a country where few abstained from drink, both understood and condemned Russia’s vodka addiction as central to an autocratic system that denied individuals their basic human rights and hindered their personal fulfillment.

A Surreal Ride

While Solzhenitsyn and Sakharov were the reluctant celebrities of the Soviet dissident movement, many poignant social criticisms were written under assumed names and disseminated through the

samizdat

underground. My all-time favorite is a short 1968 novel by Venedikt Erofeyev called

Moskva-Petushki

, sometimes translated as

Moscow to the End of the Line

. David Remnick, editor of the

New Yorker

, called it “the comic high-water mark of the Brezhnev era” and picked it as his favorite obscure book.

19

It is easy to see why.

Moscow to the End of the Line

may well be the first work of gonzo journalism. A satirical firsthand account steeped in humor, sarcasm, and copious profanity, it is a Soviet

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

written three years before Hunter S. Thompson’s descent into drug-addled hallucinations while searching for the American dream in the desert southwest. In Erofeyev’s counterpart we

follow the vodka-, sherry-, wine-, vermouth-, and eau-de-cologne-swilling alcoholic Venya, who has just spent his last kopecks on a suitcase full of liquor “and a couple of sandwiches so as not to puke” for the train ride from Moscow to his much-embellished childhood home of Petushki some eighty miles distant.

20

Did Venya ever find what he was seeking? We may never know. As reality melts into drunken hallucination, only his blackouts seem definite.

Even before the alcoholic haze sets in, Venya describes getting canned as foreman of a cable-laying crew for playfully charting his comrades’ alcohol consumption. “We pretend to work, they pretend to pay us,” was the unofficial motto of the

zastoi

era, which Venya took to the extreme.

In the morning we’d sit down and play blackjack for money. Then we’d get up and unwind a drum of cable and put the cable underground. And then we’d sit down and everyone would take his leisure in his own way. Everyone, after all, has his own dream and temperament. One of us drank vermouth, somebody else—a simpler soul—some Freshen-Up eau de cologne, and somebody else more pretentious would drink cognac.… Then we’d go to sleep.

First thing next morning, we’d sit around drinking vermouth. Then we’d get up and pull yesterday’s cable out of the ground and throw it away, since, naturally, it had gotten all wet. And then what? Then we’d sit down to blackjack for money. And we’d go to sleep without finishing the game.

In the morning, we’d wake each other up early. “Lekha, get up. Time to play blackjack.” “Stasik, get up and let’s finish the game.” We’d get up and finish the game. And then, before light, before sunrise, before drinking Freshen-Up or vermouth, we’d grab a drum of cable and start to reel it out, so that by the next day it would get wet and become useless. And, so, then, each to each his own, for each has his own ideals. And so everything would start over again.

Erofeyev’s satire wasn’t much of an exaggeration. In a fitting epitaph to the entire era of Brezhnevite stagnation, a loaded Venya utters his sodden tribute: “Oh, freedom and equality! Oh, brotherhood, oh, life on the dole! Oh, the sweetness of unaccountability, Oh, that most blessed of times in the life of my people, the time from the opening until the closing of the liquor stores.”

21

The

samizdat

underground didn’t just disseminate trenchant works of fiction—much nonconformist literature was academic: historical, economic, social, and political critiques of the autocratic system in which alcohol played a major role.

Lies, Damned Lies, And Soviet Statistics

The official position of the Communist Party on any question of significance was articulated in the

Big Soviet Encyclopedia

. When it came to its drinking problem, the official line was that the Soviet Union was a largely temperate nation, steadily working to eliminate the alcoholism that was a remnant of the capitalist past: “In Soviet society alcoholism is considered an evil, and the fight against it is carried on by the state, Party, Trade-Union, and Komsomol (Communist Youth League) organizations and health agencies. Great importance is attached to measures of social influence, to raising the cultural level of the population, and to overcoming the the so-called alcoholic traditions which exert an influence on the youth.” Apparently they were making great strides: the official Stalin-era consumption figure of 1.85 liters of pure alcohol per person annually was far below the 5.1 liters in the United States or the 21.5 liters in France.

22

When it came to the central paradox of vodka politics, namely, the state’s profiting from the alcohol trade: “vodka prices are fixed by the Soviet state at a level which facilitates the struggle against alcoholism,” if we are to believe the official line. “In the USSR the production of vodka is not governed by fiscal purposes and the income obtained from selling it accounts for an insignificant proportion of the state’s revenue.”

23

Well, if the first step in Khrushchev’s thaw was his “Secret Speech” of February 1956, perhaps the second came three months later with the publication of the Soviet annual statistical handbook,

The National Economy of the USSR

. This statistical digest stood on the reference shelf of virtually every research library in the Soviet Union and abroad. They were flawed and incomplete, but for those who knew where to look, these figures told a dramatically different tale from the official narrative.

24

Samizdat

researchers in the Soviet Union and a small cadre of foreign specialists used these government data to highlight the gaping chasm between image and reality in social well-being.

The most detailed study was undertaken by a shadowy academic known only as A. Krasikov, who wrote a series of underground articles declaring vodka “Commodity Number One” in the Soviet Union. As it turns out, A. Krasikov was a pseudonym of former

Izvestiya

reporter Mikhail D. Baitalsky—whose true identity was only revealed after his death in 1978. “The late M. D. Baitalsky may rightly be considered one of the most talented publicists of contemporary, nonconformist, native literature,” declared his

samizdat

obituary.

25

A Trotsky devotee, he secretly chronicled efforts to oppose Stalin’s rise in the 1920s. In the Great Purge of the 1930s Baitalsky was fired from

Izvestiya

, denounced by his wife, and sent to the notorious forced-labor camp at Vorkuta. Following a brief “respite” to the Eastern Front in World War II, he was sentenced to work in the

scientific institute described in Solzhenitsyn’s

First Circle

before being released in 1956 during Khrushchev’s thaw.

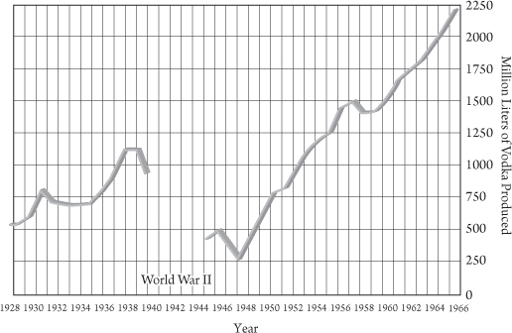

Like Solzhenitsyn and Sakharov, Baitalsky was a teetotaler who was alarmed that instead of combating alcohol as state propaganda claimed, the Kremlin was ramping up production to unprecedented levels. By 1960 vodka output was already double prewar levels, while beer production had quadrupled—and this according to the government’s own statistics!

26

The official State Statistical Commission (Goskomstat) abstracts showed the upward march not only of alcohol production but also of a whole raft of related social indicators that did not bode well for the Soviet public—crimes, suicides, abortions, and even infant mortality numbers were actually increasing rather than decreasing.

When Khrushchev was ousted in 1964, the thaw in Soviet statistics ended as well. With vodka factories running full tilt, and Goskomstat chronicling the consequences, Brezhnev simply halted the publication of such embarrassing statistics. But that did not deter Baitalsky.

Unlike the unflattering statistics on infant mortality that simply vanished without a trace, Baitalsky noted that as soon as the statistical column on “alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages” disappeared, a separate column for “other foodstuffs”—which typically included spices, soybeans, mushrooms, and vitamins—suddenly expanded tenfold. If the state statistical handbooks are to be believed, by 1970 Soviets were spending 27 billion rubles every year on these “other foodstuffs,” of which he estimated that 23.2 billion was spent on vodka.

27

Baitalsky also noted a staggering rate of growth in this miscellaneous category in contrast to the usually stable expenditures on spices, soybeans, and the like. Comparing these estimates with the other consumer expenditures—from household furniture to printed publications—he deduced that, at some twenty-three billion rubles spent per year, “Alcohol is, indeed, the leading commodity among all those purchased by our people. It has become Commodity Number One, with Number Two (‘clothing and underwear’) and Number Three (‘meat and sausages’) lagging behind not by half a length, not by half a billion rubles, but by 9 and 12 billion respectively.”

28

Somehow, Baitalsky got his hands on an in-house report from Glavspirt, the chief administration of the alcohol industry. Even omitting beer, wine, illicit home brew and poisonous surrogates, these government figures on per capita vodka consumption (

figure 16.1

) show a dramatic—and damning—expansion of state alcohol production interrupted only by the horrors of total war. Against the Kremlin’s data blackout, even such fragmentary figures demonstrate both the staggering increase of alcohol consumption and the government’s role in promoting it. Back in the tsarist era in 1913, Russians drank an average of 7.75 liters of pure alcohol per year. While the Soviets claimed that alcoholism—as a remnant of the capitalist past—would wither away under communism, even after fifty years of “withering,” in 1967 the Russians were quaffing up to 9.1 liters of pure alcohol per person annually from state vodka factories alone.

29

Figure 16.1

L

EGAL

V

ODKA

P

RODUCTION IN THE

S

OVIET

U

NION

, 1928–1966. Source: Mikhail Baitalsky [A. Krasikov], “Tovar nomer odin,” in Roy A. Medvedev, ed.,

Dvadtsatyi vek: Obshchestvenno-politicheskii i literaturnyi al’manakh

, vol. 2 (London: TCD Publications, 1977), 118.

Baitalsky further underscored vodka’s centrality to the autocratic state, estimating that more than ninety kopecks from every ruble spent on vodka went directly into the treasury, making vodka both the single largest and most lucrative sector of the entire Soviet economy.

30

For the government, vodka is the perfect commodity.