Vodka Politics (50 page)

Authors: Mark Lawrence Schrad

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Europe, #General

Liquor And The Thaw

In February 1956—three years after the death of Stalin—his successor Nikita Khrushchev took the first step in confronting Stalin’s totalitarian legacies by delivering the so-called “Secret Speech” to the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party. Before a closed session of party elites, for four hours past midnight, a sullen and tempered Khrushchev criticized Stalin’s personality cult, the wholesale deportation of national minorities, and his ruthless purges of the party and military. The speech began a decade-long thaw in Soviet society, culture, and even foreign policy. Censorship was eased, consumer-based economic reforms were enacted, and millions of political prisoners returned from Siberian gulags.

One exonerated former prisoner was an aspiring writer, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. A twice-decorated military commander, Solzhenitsyn was arrested in 1945 during the Red Army’s German offensive for making derogatory comments about comrade Stalin. After being beaten and interrogated by the NKVD at the Lubyanka Prison, he was convicted for counterrevolutionary activity under the infamous Article 58 of the penal code and sentenced to eight years hard labor—the brutality and senselessness of which he would describe in a string of scathing, historically based novels. His first—

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

—was published in 1962 with the personal blessing of Khrushchev, who defended it before the Politburo as social catharsis: “There is a Stalinist in each of you,” Khrushchev railed, “there’s even some of the Stalinist in me. We must root out this evil.”

2

Ivan Denisovich

was a hit—not only in the West, where it highlighted the severity of Soviet human rights violations, but in the Soviet Union, too. Just as during Russia’s literary golden age of the nineteenth century, government censorship still prevented direct criticism of the state and its leaders, but literature still provided a veil for political discussions. And just as under the tsars, critics seized upon vodka politics as a way to confront the Soviet autocracy.

If the 1960s were the new 1870s, then certainly Solzhenitsyn was the new Tolstoy: beyond their similar physical stature, both were war heroes-turned-historical dramatists, both were prolific writers, both wrote biting condemnations of the ruling autocracy that made them influential moral authorities, and—notably—both were teetotalers whose rejection of alcohol fundamentally conflicted with the autocratic political system. Even battling Nazis in the trenches, where “vodka consumption was second only to battlefield courage as a mark of valor,” Solzhenitsyn still refused to drink.

3

Like Tolstoy, Solzhenitsyn’s social criticisms are drenched in vodka. One of his earliest novellas,

Matryona’s House

, describes Soviet rural life in the 1950s but is strikingly reminiscent of imperial days. The hero, Matryona, reluctantly

consents to give up part of her tiny hut to her relatives, who want to use the wood for their house in a village twenty miles away. While the men tear down part of the house, the women distill

samogon

—as women traditionally did—as payment for the ten men hauling the wood on a borrowed tractor. After a boisterous evening of drinking, even Matryona joined the men on their ill-fated, drunken escapade. In the middle of the night, the narrator staying in Matryona’s humble cottage is visited by police, demanding to know whether the group had been drinking. Knowing “Matryona could get a heavy sentence for dispensing illicitly distilled vodka,” the narrator lies to the officers at the door, even while the foul stench of half-drunken bottles of moonshine wafted in from the kitchen. As the police leave, they let it out that Matryona and the drunken men were killed by a train as the tractor got stuck on a railroad crossing.

4

Beyond the usual array of drunken characters and drinking parties, Solzhenitsyn’s

Cancer Ward

(1968) also highlights the use of poisonous alcoholic surrogates—as intoxicant or folk medication—for inmates facing terminal cancer.

5

He also uses vodka to take jabs at the systemic corruption. While lamenting that officials always expected bribes simply to perform their assigned duties, one worker worried that if they did not “‘come across’ with a bottle of vodka,” the bureaucrats “were sure to get even, to do something wrong, to make her regret it afterwards.”

6

(Solzhenitsyn wasn’t alone in linking vodka and Soviet corruption: when referring to

khrushchoby

—the shoddy four- or five-story tenements hastily built during the Khrushchev years—the popular joke was that some only have four stories because the fifth was stolen and sold for vodka.)

7

All the same, like those of Tolstoy, virtually all of Solzhenitsyn’s works use drunken tragedy to both expose the autocracy and share the author’s disdain for drinking.

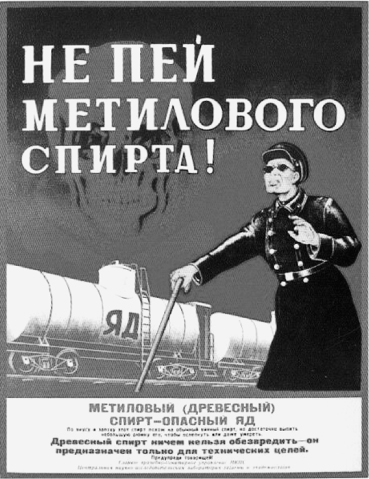

D

ON’T

D

RINK

M

ETHYL

A

LCOHOL

! (1946). “Methyl alcohol (wood spirits) is a dangerous poison.”

Unfortunately the cultural, political, and social openness of the Khrushchev era was doomed by the bombastic premier’s domestic gaffes and foreign policy fiascoes. To Mao Zedong in China, Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech” was a sell out, and his de-Stalinization was misguided, and this disagreement drove a wedge between the two communist giants.

Détente

with the Americans was sidetracked by one crisis after another: the downing of an American U-2 spy plane in 1960, the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961, and finally the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, which pushed the world to the brink of thermonuclear war. Meanwhile, Khrushchev’s domestic reforms went nowhere. His vaunted campaign to transform the arid Kazakh steppe into rich farmland turned to dust. All this, when added to his brash and erratic behavior, such as his embarrassing shoe-banging incident at the UN, culminated in Khrushchev’s forced retirement in October 1964. His replacement, Leonid Brezhnev, put a quick end to the “thaw”—clamping down on expression and opposition. The eighteen years of Brezhnev’s rule, from 1964 until his death in 1982, was an era of

zastoi

, or stagnation, in the economy, arts, and society.

Brezhnev embodied the corruption, decay, and drunkenness that mushroomed in Soviet society under his tutelage. Dour and stodgy, he had none of the in-your-face exuberance of Khrushchev. Some of his closest associates depict Brezhnev as an unstable and increasingly senile alcoholic who, in failing health, stumbled into such disastrous decisions as the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979.

Anatoly Dobrynin—the Soviet ambassador to the United States—seemed particularly irked by Brezhnev’s incessant drinking, especially since he was usually on the receiving end of the general secretary’s drunken, late-night, prank calls on the Kremlin’s hotline to the Soviet embassy in Washington. After Brezhnev’s death, his longtime foreign minister Andrei Gromyko was asked whether Brezhnev had a serious drinking problem. “The answer,” he replied after a reflective pause, “is Yes, Yes, Yes.” Gromyko admitted “It was perfectly obvious that the last person willing to look at this problem was the general secretary himself.”

8

Brezhnev’s alcoholism was a product of his rise through the military under Stalin. The morning after Brezhnev’s extremely well-lubricated seventieth birthday celebration in 1976, advisor Anatoly Chernyaev remembered how—still

visibly intoxicated—Brezhnev waxed nostalgic for getting drunk during the Stalin years. Brezhnev reminisced how, as a Red Army hero, he got so hammered at Stalin’s World War II victory banquet that he stopped in the Kremlin courtyard and carried on a meaningful conversation with the

tsar-kolokol

—the world’s largest brass bell, which was cast in the eighteenth century but dropped and broken before it could ever be rung.

9

For dissident writers like Solzhenitsyn, tightening censorship under Brezhnev not only forced their writings underground; it also sharpened their criticisms. The KGB kept him under close surveillance and routinely seized his manuscripts, and the world-famous writer could no longer find a willing publisher. In 1969 Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Union of Writers. The following year he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, which he could not accept for fear of not being allowed to return home to the USSR. Sheltered by a secretive circle of underground friends, Solzhenitsyn secretly worked on his magnum opus, the three-volume

Gulag Archipelago

. Completed in 1968,

Gulag

was a bombshell—chronicling not only the unimaginable hardships in the camps but also the entire system of political repression from arrest, detention, and interrogation to transportation and incarceration. Smuggled out of the country to be published abroad (

tamizdat

—literally “publishing over there”) in late 1973, it was hailed by America’s foremost Kremlinologist-diplomat George F. Kennan as “the greatest and most powerful single indictment of a political regime in modern times.”

10

On September 5, 1973, Solzhenitsyn candidly wrote to Brezhnev, articulating what he saw as the most pressing challenges for the Soviet leadership both at home and abroad. With surprising audacity, Solzhenitsyn described the malaise in the economy, dilapidated collective agriculture, outdated military conscription, the exploitation of women, the lack of societal morality, and a destructive corruption that pervaded the entire Soviet system. “But even more destructive is vodka,” continued Solzhenitsyn’s Tolstoyan indictment of the state’s complicity in the alcohol trade.

So long as vodka is an important item of state revenue nothing will change, and we shall simply go on ravaging people’s vitals (when I was in exile, I worked in a consumers’ cooperative and I distinctly remember that vodka amounted to 60 to 70 percent of our turnover). Bearing in mind the state of people’s morals, their spiritual condition and their relations with one another and with society, all the

material

achievements we trumpet so proudly are petty and worthless.

11

Solzhenitsyn was a nationalist and Slavophile who viewed the alien, European ideology of Marxism–Leninism as the root cause of all of Russia’s ills—corrupting the spirituality and the morals of the people through “that same old vodka.”

12

Brezhnev never wrote back, but the Kremlin responded in other ways. In February 1974—five months after penning his letter—Solzhenitsyn was arrested, stripped of his citizenship, and deported. He ultimately settled in the secluded hills of Cavendish, Vermont. Though Solzhenitsyn was persona non grata in the Soviet Union, his works were published to greater acclaim abroad and were often smuggled back in to the Soviet Union where his—and other dissidents’—banned works were circulated and reproduced by hand through underground networks in a process known as

samizdat

—or self-publishing.

With Solzhenitsyn in exile, the main dissident voice in the USSR belonged to Andrei Sakharov—nuclear physicist and father of the Soviet hydrogen bomb. Sakharov’s early warnings of the dangers of nuclear holocaust gave way to a broader criticism of the oppressive Soviet system itself. Like Solzhenitsyn, he was denounced as a traitor by his government. Like Solzhenitsyn, Sakharov wrote brazen letters to the Kremlin leadership—and also like Solzhenitsyn, Sakharov took particular issue with Soviet vodka politics. “Our society is infected by apathy, hypocrisy, petit bourgeois egoism, and hidden cruelty,” Sakharov wrote in a second letter to Brezhnev in 1972. “Drunkenness has assumed the dimensions of a national calamity. It is one of the symptoms of the moral degradation of a society that is sinking ever deeper into a state of chronic alcohol poisoning.”

13

Increasingly famous for advocating democracy and human rights, Sakharov understood alcohol’s centrality to the system of repression: trapped in fear, unable to emigrate, and deprived of a voice in politics, the dissatisfied Soviet people turned to “internal protest” that takes on “asocial forms”: drunkenness and crime. “The most important and decisive role in maintaining this atmosphere of internal and external submission is played by the powers of the state, which manipulates all economic and social control levers. This, more than anything else, keeps the body and soul of the majority of people in a state of dependence.”

14

That the state itself profits from this dependence, while the people grapple with the social, health, and criminal consequences only compounds the tragedy. Accordingly, in his letters and statements, Sakharov railed not only against the death penalty and torture but also for education and healthcare reform and remedying the alcohol problem.