Vodka Politics (64 page)

Authors: Mark Lawrence Schrad

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Europe, #General

Alcohol and the Demodernization of Russia

From the outset, Russia’s reformers were in uncharted waters and sinking fast. The received wisdom going back to Karl Marx was that the great challenge of history would be the transition from capitalism to communism, not the other way around. Right up to the collapse of the Berlin Wall, few people thought a reversion to capitalism was even possible. Even fewer thought about

how

to do it. Reformers in the communist satellites of Eastern Europe and the Soviet homeland thought they knew what hardships it would entail—unemployment, dislocation, and economic contraction—but they could only guess how deep the pain would be or how long it would last.

To right the ship, Boris Yeltsin—fresh from victory over the August 1991 hardline coup—pushed for radical reforms. “The time has come to act decisively, firmly, without hesitation,” he declared. Top experts drafted a “500 Days” program that denationalized land and housing, freed fixed prices, abolished subsidies for inefficient firms, and implemented austere fiscal and monetary reforms. “The period of movement with small steps is over.”

1

Yet he too was uncertain about the suffering it would entail.

“I have to tell you frankly: today in the severest crisis we cannot carry out reform painlessly. The first step will be most difficult. A certain decline in the standard of living will take place,” Yeltsin said. In preparing the country for the shock therapy of rapid liberalization he claimed, “It will be worse for everybody for about half a year. Then, the prices will fall and the consumer market will be filled with goods. And toward the fall of 1992… the economy will stabilize and lives will gradually improve.”

2

But things did not improve. Into 1993 Russia was still stuck in a hyperinflationary spiral, which wiped out most Russians’ entire life savings. With consumer prices rising over two thousand percent per year, the ruble became worthless, eroding the real wages of those who still had jobs and plunging millions into abject poverty. The average Russian schoolteacher’s monthly salary during the

1990s was just $34, well below their counterparts in Thailand, and often below the government’s official “minimum subsistence” (i.e., poverty) level. Even after the economy stabilized at the end of the millennium, one study concluded that the minimum monthly income in Novgorod region was barely enough to feed five live cats.

3

Economic indicators were equally frightening: Russia produced two hundred and fourteen thousand tractors in 1990. By 1994 it was fewer than twenty-nine thousand—a collapse of eighty-seven percent. The production of all foodstuffs in 1994 was half what it was under Gorbachev and had still farther to fall. By the late 1990s, Russia’s annual grain harvests were smaller than they were under the tsars before World War I. The Red Cross even mobilized food aid to avert a potential famine.

4

The economic hardships helped unleash a tidal wave of drunkenness larger than anything seen before in Russia’s long, inebriated history. Russia’s heavy-drinking men were dying off at an alarming rate, with deaths from alcohol poisonings, liver and cardiovascular diseases, drunken homicides and suicides all skyrocketing. Russian male life expectancy dropped from sixty-four to fifty-eight—worse even than under Stalin’s tyranny.

5

In many ways it seemed that Russia was not simply in the throes of economic depression but was somehow regressing backward in time—undoing all of the economic and social progress that had been achieved through such tremendous human sacrifice under the Soviets. From the most remote regions to the capitals Russia experienced a “steady retreat of civilization”: citizens were forced into premodern survival strategies as the Soviet-era industrial, commercial, healthcare, and law enforcement systems corrupted, decayed, and collapsed around them.

6

“It’s difficult to talk about the twenty-first century when you’re sitting here reading by candlelight,” confided one teen in Russia’s desolate Kamchatka Peninsula on the eve of the new millennium. “The twenty-first century does not matter. It’s the nineteenth century here.”

7

This was no ordinary economic recession.

From “Transition” To Demodernization

To read the economic literature on Russia’s “lost decade” of the 1990s is to get lost in the technocratic language of “-ions”: stagnation, transition, recession, depression, contraction, liberalization, inflation, stabilization, deregulation, denationalization, privatization, commercialization. Examining developments through such high-altitude, macroeconomic “-ions” conveniently—and perhaps deliberately—blinds us to the true cost of a decade-long turmoil that by some estimates reduced economic output by over fifty percent—far worse even than

the Great Depression.

8

Economists’ estimates of diminishing GDP—even on a per capita basis—tell only one side of the story.

In the wake of Russia’s 1998 default, NYU professor Stephen F. Cohen described the horrific scope of the realities on the ground: “When the infrastructures of production, technology, science, transportation, heating and sewage disposal disintegrate; when tens of millions of people do not receive earned salaries, some 75 percent of society lives below or barely above the subsistence level, and millions of them are actually starving; when male life expectancy has plunged as low as fifty-eight years, malnutrition has become the norm among schoolchildren, once-eradicated diseases are again becoming epidemics, and basic welfare provisions are disappearing; when even highly educated professionals must grow their own food in order to survive and well over half the nation’s economic transactions are barter—all this, and more, is indisputable evidence of a tragic ‘transition’ backward to a premodern era.” Cohen concludes that “so great is Russia’s economic and thus social catastrophe that we must now speak of another unprecedented development:

the literal demodernization of a twentieth-century country

”.

9

Although neither Cohen nor any other scholar have elaborated on “demodernization” as a concept, his underlying claim is most assuredly true: adding social indicators to economic ones, we find that not only was Russia’s “lost decade” worse than either Japan’s “lost decade” or America’s Great Depression in degree, but it was also fundamentally different in kind—a process of destruction and deindustrialization without parallel in the peacetime history of the world.

10

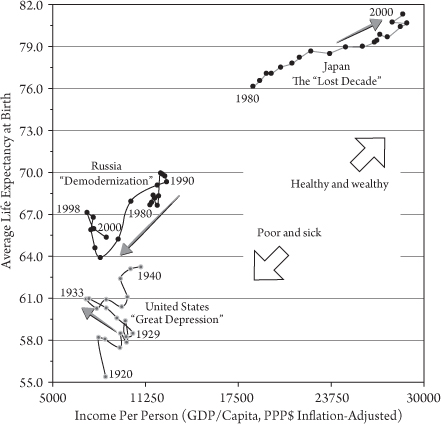

Perhaps the best way to illustrate this difference is to fold social indicators into the conventional economic comparisons. Recently, sword-swallowing Swedish statistician Hans Rosling and his Gapminder Foundation have developed just such an approach. Bridging the “gap” between inaccessible social-scientific data and a broader public utilization, Gapminder is a user-friendly clearinghouse of official health, economic, and social statistics compiled by national and international agencies around the globe, which facilitates comparisons across countries and over time. For instance, by plotting a standard indicator of prosperity (income per capita) on the horizontal axis and social well-being (average life expectancy) on the vertical, Rosling animates over two hundred years of data for two hundred countries to show how, due to industrialization and modernization, all countries have generally moved toward the upper-right quadrant—his so-called “healthy, wealthy corner”—where all modern states aspire to be.

11

Following Rosling,

figure 20.1

presents twenty-year sections of data: Russia and Japan from 1980 to 2000 and the United States from 1920 to 1940. The results are telling: Japan’s “lost decade” was a prolonged recession: economic growth may have slowed, but Japan was still progressing toward the healthy–wealthy corner. By contrast, America’s experience in the Great Depression was movement toward the upper-left quadrant: the economy was contracting, yet the overall health of the population actually improved.

Figure 20.1

H

EALTH AND

W

EALTH

I

NDICATORS DURING

M

AJOR

E

CONOMIC

C

RISES.

Sources: Life expectancy figures derived from the Human Mortality Database,

www.mortality.org

. For notes on Gapminder data collection and standardization of GDP per capita statistics see

http://www.gapminder.org/documentation/documentation/gapdoc001_v9.pdf

. For income per person for Japan and Russia see Angus Maddison, “Historical Statistics for the World Economy: 1–2006 AD” (2008),

www.ggdc.net/maddison/

. For income per person in the United States see Robert J. Barro and José F. Ursúa,

Macroeconomic Crises since 1870

, NBER Working Paper No. 13940 (Cambridge, Mass.: NBER, April 2008). Data are from

http://rbarro.com/data-sets/

.

These experiences were fundamentally different—not only in degree but also in kind—from what Russia endured: moving dramatically away from the healthy–wealthy corner for the duration of the 1990s, becoming both far poorer and more sickly. The only other examples of such dramatic retrograde motion come from countries devastated by war: World War I and the 1918 flu pandemic, Germany in World War II, Bosnia in the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s. To have such dramatic backsliding in peacetime is unheard of.

What happened?

My argument here is straightforward: economic crisis plus the legacies of vodka politics lead to demodernization, which undercut Russia’s long-term potential for both economic growth and successful democratization.

The End Of Autocracy, The End Of Vodka Politics?

Vodka politics has been the central pillar of Russian statecraft since the earliest tsars. Yet so radical was the break with the Soviet past that even the mighty state vodka monopoly fell to liberalization, marketization, and democratization.

In January 1992 the old Soviet vodka monopoly was abolished. The once-fixed price of alcohol would now be set by supply and demand, capped with an eighty percent excise tax. The state maintained some control by monopolizing the necessary raw materials for distillation—ethyl alcohol—which could only be

legally

procured from one of the 162 state-run rectification facilities at a price that reflected the additional taxes levied on it.

12

The old Soviet alcohol producers and importers were reorganized and privatized while private distilleries and

samogon

moonshiners flourished. To evade government taxes and regulations most alcohol production shifted off the books and into the black market. Untaxed imports flooded in from the West, and illegal shipments arrived by the trainload from Belarus and Ukraine. Vodka was everywhere. A half-liter bottle of questionable origins and ingredients could be had for a dollar. Whereas vodka contributed almost a third of the Soviet superpower’s budget, by 1996 that share had plummeted to three percent—with the money that once would have gone to the treasury ending up in the hands of black market producers and bootleggers.

13

“The tradition of drinking oneself under the table,” once quipped Soviet dissident Mikhail Baitalsky, is “the popular tradition most profitable to the state.”

14

Yet just because the state was no longer profiting as it used to did not mean that Russians instantly sobered up. Government policies change quickly; cultures change glacially. So although the Soviet autocracy and monopoly were suddenly gone, they left behind an entire population that for generations had relied on vodka as “the Russian god”—omnipotent and omnipresent, in good times and bad.

15

And times were getting very, very bad.

With their life savings gone, jobs evaporating, the uncertainty of economic calamity, and the lack of steady leadership, is it any wonder that more and more Russians turned to vodka, practically the only product that was both cheaper and more available than under the Soviets?

16

By the time of Yeltsin’s 1996 reelection bid, per capita alcohol consumption approached fourteen liters of pure alcohol per year—returning to the astronomical levels of the Brezhnev era and erasing what little benefits remained of Gorbachev’s well-intentioned anti-alcohol program.

17