Vodka Politics (68 page)

Authors: Mark Lawrence Schrad

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Europe, #General

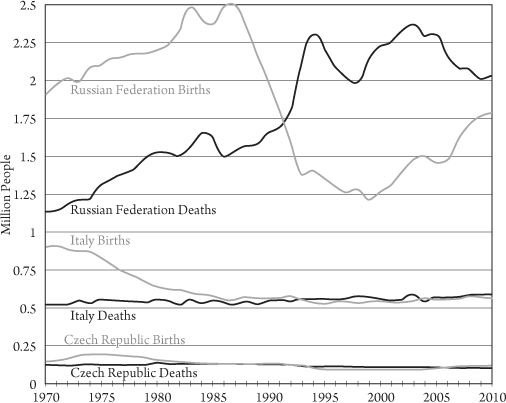

Figure

21.1 T

HE

R

USSIAN

C

ROSS

: A

NNUAL

B

IRTHS AND

D

EATHS IN THE

R

USSIAN

F

EDERATION

, I

TALY AND THE

C

ZECH

R

EPUBLIC

, 1970–2010. Sources: Goskomstat Rossii,

http://www.gks.ru/dbscripts/Cbsd/DBInet.cgi?pl=2403012

; Istat,

http://demo.istat.it/index_e.html

; Czech Statistical Office,

http://www.czso.cz/eng/redakce.nsf/i/population/

.

“We can’t believe what’s become of our country. It’s worse than the war,” said one elderly woman in the hospital ward, choking back tears. For the past eight months she had spent her entire pension on prescriptions that should have been covered under the universal healthcare bequeathed by the Soviets. “Under the communists we were alive,” she says, suggestive of demodernization’s undermining of political values. “Now we are dying with this kind of democracy.”

Over 75 percent of Russian patients have to resort to bribery, the

60 Minutes

narrator explains.

“And they call this ‘free public health’”—Fenton sarcastically puts it to his host.

“Well, if

you

want to call it that, fine,” Feshbach shoots back. “I don’t.”

7

A resource-starved healthcare system alone cannot explain the plummeting statistics. In fact, when compared to Brazil, India, and China (Russia’s other BRIC counterparts sharing a similar level of economic development), Russia not only spends more per capita on healthcare, but it also has more medical professionals. More doctors and more money translates into better health the world over—except in Russia, where life expectancy is still a decade less than models would predict based on healthcare availability and expenditure statistics. Russia’s nagging ailment isn’t so easily “cured,” at least in the epidemiological sense.

8

Russia actually has many ailments beyond its alcoholic affliction. In the 1990s, AIDS entered the former Soviet bloc primarily through drug addicts sharing dirty needles. While an outmoded HIV-screening system has allowed the state to downplay the prevalence of the disease, international organizations warn of a potential AIDS disaster looming just below the surface. Beyond AIDS, there was an explosion in diseases that have been all but wiped out in the West: polio, measles, rubella, and one hundred fifty thousand new cases of tuberculosis annually—half of which are of a mutated TB strain that festers in Russia’s crowded prisons and is stubbornly resistant to all known treatments.

9

Add to that the polluted drinking water that spreads bacterial dysentery, malaria, and diphtheria.

“This is a

huge

catalogue of horrors,” Fenton notes, as they continue to walk through the gently falling Moscow snow.

“I’m sorry,” Feshbach stops, as if to emphasize the point, “that’s why people thought that I spoke in hyperbole. That is, I couldn’t be right about all of this. But unfortunately I feel I am.”

Still, the single greatest cause of this dismal state of affairs is vodka. Soviet medical experts used to call alcohol “Disease #3,” as the third leading cause of death, behind only cancer and cardiovascular diseases. By the 1990s vodka had leapfrogged both, officially becoming “the main killer of Russians.” Alcohol-related mortality in Russia was the highest in the entire world.

10

How could it come to this? Against images of staggering homeless drunks, vodka kiosks, and Yeltsin’s drunken Berlin embarrassment, Fenton narrates: “To quench its sorrows, the average Russian male now guzzles an incredible half-a-bottle of vodka per day. And remember, that’s the

average

.” That’s roughly 180 bottles of vodka per year.

11

Stop for a minute—let that sink in.

With illicit

samogon

and third-shift vodka permeating the market, calculating alcohol consumption is a tricky matter. The best estimates are that in the 1990s Russians quaffed some fifteen to sixteen liters of pure alcohol annually—doubling the eight-liter maximum the World Health Organization deems safe. Making accommodations for nondrinkers (children and abstainers) and how

much men drink relative to women, as well as their drink preference, these abstract numbers mean that the average drinking Russian man downs thirteen bottles of beer and more than two bottles of vodka every week—week in and week out.

12

Not surprisingly, Russia is either at or near the top of every list of the world’s hardest-drinking nations, along with Ukraine, Moldova, the Baltic states, Hungary, and the Czech Republic. Yet even though all of these countries endured post-communist transitions, perhaps only Ukraine has had a collapse in public health indicators similar to that of Russia (see

chapter 20

). How are we to make sense of this?

The answer is that the destructiveness of alcohol depends not just on how much alcohol is consumed, but on what kind and

how

it is consumed. The Czechs, for instance, have long had a beer-drinking culture, with the average man downing only two-thirds of a bottle of spirits per week but sixteen beers and a bottle of wine. In wine-drinking Hungary, the average man quaffs the same two-thirds of a bottle of liquor along with eleven beers and two and a half bottles of wine per week. Each scenario describes a lot of heavy drinking, but the legacy of vodka politics reflected in Russians’ preference for potent, distilled liquors over milder, fermented beer or wine is the difference between a moderate social-health concern and a full-blown demographic crisis.

13

Consider alcohol poisoning. Four hundred grams of pure ethyl alcohol is usually enough to kill you. If you’re a beer drinker, to get that much pure alcohol into your bloodstream, you’d have to down almost an entire keg in one sitting. In the United States, every year there are a few tragic cases—usually college students—who die in such a manner, but a beer drunk usually passes out clutching the toilet bowl long before he approaches a lethal dose. The same thing is true for wine drinkers, who tend to fall asleep well before downing a lethal five and a half bottles at once. Passing out is the body’s defense mechanism—shutting down before you completely poison yourself. Due to vodka’s higher potency, it takes only two half-liter bottles to deliver a lethal dose: an amount that can be more easily consumed before the body can shut itself down.

14

“It’s not just that consumption is high, although it is,” Feshbach explained about Russia’s peculiar drinking culture. “It’s the way they consume. It’s chug-a-lug vodka drinking that starts at the office during the morning coffee break and goes right into the nighttime.”

15

Until recently, instead of twist-off lids, vodka bottles in Russia came with tear-off caps that could not be resealed. Why would you want to put the lid back on? A “real man” would finish off the entire bottle rather than let it go to waste. Moreover, in contrast to the communal drinking culture of the imperial past, Russia’s modern, individualistic drinking culture means that Russians today often drink alone (and without proper nourishment), only compounding their health problems.

16

A further complication, as we found

in

chapter 7

, is the unique practice of

zapoi

: when an individual withdraws from social life—sometimes for days at a time—to go on an alcohol-fueled bender. This binge drinking leads to higher rates of sudden heart failure from acute stress on cardiovascular muscles.

17

This is to say nothing about the quality of vodka. With

samogon

moonshine and unregulated third-shift vodka making up more than half of the market, there was little quality control in the 1990s. To cut costs, some unscrupulous alcohol producers even cut their vodka with toxic technical, medical, or industrial alcohols to save a few rubles.

18

Then come the alcohol surrogates: from antifreeze and break fluid to eau-de-cologne and cleaning compounds. Recent fieldwork suggests that one in twelve Russian men—some ten million people or more than the entire population of Hungary—regularly drinks potentially toxic medicinal or technical alcohols.

19

Not surprisingly, those who turn to such alternatives tend to be desperate men from the poorest socioeconomic groups. Also unsurprisingly, the risk of death among those who regularly drink antifreeze and other toxins is six times higher than even clinical alcoholics and a full

thirty times higher

than men who don’t drink at all.

20

In sum, the individualized culture of tossing back huge quantities of hard liquor—often of low quality or outright poisonous—has produced a level of alcohol poisonings in Russia that is up to

200 times

higher than that in the United States, making vodka the single greatest contributor to Russia’s unparalleled health disaster. When Dr. Feshbach rather nonchalantly explained to the

60 Minutes

audience that over forty-five thousand Russians died from alcohol poisoning in one year, this is how.

21

Alcohol kills in other ways, too. Notably, deaths from liver cirrhosis and chronic liver disease have steadily increased since the collapse of communism, adding another sixteen deaths per one hundred thousand throughout the 1990s. Vodka also contributes to coronary heart diseases and strokes, harms that accumulate gradually over a long period.

22

Indeed, more than half of the increase in male mortality is attributable to cardiovascular diseases in which alcohol and tobacco play a lethal role. As a consequence, in 1995 the rate of deaths from cardiovascular diseases in Russia was 1,310 per 100,000. In Spain, by contrast, it was only 268. Demographer Nicholas Eberstadt has translated these numbers with brutal clarity: “the world has never before seen anything like the epidemic of heart disease that rages in Russia today.”

23

But as Eberstadt explains, deaths from heart disease are compounded by fatal injuries for which Russian men “have no peers.”

24

This is especially true of men who die suddenly in the prime of life. In a survey of a typical city morgue, fifty-five percent of the corpses had dramatically elevated blood-alcohol levels. The majority of murder victims and half of suicide victims were drunk at the time of death. Statistically speaking, alcohol is complicit in the vast majority of

robberies, home invasions, burglaries, car thefts, and hooliganism as well as traffic accidents, drownings, suicides, wife beatings, rapes, and murders.

25

Back in Moscow, CBS journalist Tom Fenton was understandably flabbergasted when a hospital’s chief surgeon matter-of-factly told him that ninety-nine percent of all injuries treated at his hospital were caused by alcohol.

“Ninety nine percent?!” Fenton exclaimed—doubling over with shock as though he had been punched in the gut.

Ringed by patients with rudimentary tourniquets, the surgeon nonchalantly replied: “

Da—99 protsentov

.”

It goes without saying that all of these problems are only made worse by the collapse of the public health infrastructure. Take, for instance, the sixteen percent of working-age men who are problem drinkers or the five percent of the able-bodied population considered to be clinical alcoholics. The vast majority of these unwitting victims of Russia’s autocratic vodka politics go without treatment. The demodernization of the 1990s ravaged the specialized hospitals and outpatient clinics confronting this epidemic alcoholization of Russian society.

26

Taken together—directly and indirectly—vodka claims over four hundred and twenty-five thousand Russian souls every year and is the single greatest contributor to the dismal post-Soviet life-expectancy statistics, especially among men.

27

Consider this: in the nondrinking cultures of the Muslim world, women live on average only four to five years longer than men. In the primarily beer-drinking countries—like those in Western Europe—men die about six years earlier than women. In wine-drinking regions, the difference grows to eight years. But in the liquor-swilling countries of Eastern Europe, men generally die a full decade earlier. Here again Russia tips the scales, with Russian men dying a world-record

fourteen full years

before the average Russian woman.

28

More than any other statistic, the gender gap in life expectancy captures the true scale of Russia’s autocratic

vodkapolitik

legacy.