Voices from the Dark Years (10 page)

Read Voices from the Dark Years Online

Authors: Douglas Boyd

Understandably, Freeman and Cooper were hazy about exact dates by this time in their odyssey, so this destroyer may have been the same one that rescued the Legrands from Moulleau, in which case the supernumerary commander was Ian Fleming. After casting off, the White Ensign was hailed with loud cheers of

‘Vive l’Angleterre!’

from the crews of French warships at their moorings. Then followed a nail-biting few hours’ being piloted between the shifting sandbanks of the Gironde estuary on constant lookout for magnetic mines. Passing at dusk the Le Verdon memorial on the tip of the Médoc peninsula to the first ‘doughboys’ who landed there in 1917, Freeman thought it looked like a beacon whose flame had gone out, for he had seen no evidence of the ‘resistance’ of which de Gaulle had spoken on 18 June.

In the darkness of German-occupied Royan on their starboard bow, Pablo Picasso was preparing to leave his top-floor studio in a typical turn-of-the-century seaside villa built there by the city-dwelling middle classes when the railway arrived at the end of the nineteenth century. A refugee from civil war in Spain, he had been painting at Antibes in September 1939 and fled from there to Paris. The German advance had panicked him and his mistress-model Dora Maar into heading with his secretary Jaíme Sabartés and dog Kasbec for the south-western resort, where his daughter Maïa and her mother were already staying, in the belief that they would be safe there. Now that the Wehrmacht had caught up with him, he decided to take his complicated

ménage

back to Paris, where life was more amusing.

Taking refuge with friends in the Loire Valley after fleeing the capital, Simone de Beauvoir wrote of the German arrival there: ‘To our general surprise, there was no violence. They paid for their drinks and the eggs they bought at farms. They spoke politely. All the shopkeepers smiled at them.’

5

Further north, Gen Erwin Rommel was writing to his wife: ‘The war is turning into a peaceful occupation of the whole of France. The population is calm and in some places even friendly’ – as they were in the British Channel Islands, where the Wehrmacht landed on 30 June without opposition, the islands having been demilitarised a week earlier as impossible to defend.

Casualties of the German advance included one of the first tax exiles. P.G. Wodehouse, creator of Jeeves and Bertie Wooster, had arranged for himself and his wife to be warned of the German advance by British troops near their home in Le Touquet but were caught out by its speed, having refused to return to Britain earlier because their Pekinese dog would have been put in quarantine for six months. Like all male citizens of enemy powers under 60, Wodehouse was taken hostage and confined in a former mental hospital at Tost in Upper Silesia to await his 60th birthday.

One of the most bizarre jobs handed out by Pétain’s government at this time landed on the desk of Gen de la Porte du Theil, whose 7th Army Corps had fought well in Alsace and retreated in good order successively to the Marne, the Seine and the Loire, before withdrawing for regrouping at Bourganeuf near Limoges, safely inside the Free Zone. On 2 July he was CO of 13th Military Division, based in Clermont-Ferrand. Summoned to nearby Royat, where Gen Weygand’s War Ministry was in temporary accommodation, de la Porte du Theil was informed of his new posting. While all else failed in the débâcle, the bureaucracy of conscription had continued running impeccably: 70,000 20-year-old men had been called up for military service on 8 and 10 June, since when they had been without uniforms, weapons, NCOs or training. Since, under the Armistice agreement, it would have been illegal to issue them with uniforms or weapons, de la Porte du Theil asked Weygand what exactly he was supposed to do with so many useless mouths. The answer: anything that would occupy these bored and rightly angry young men.

‘And where do I get the officers to train them?’ he asked.

‘You can have the pick of the cadet schools,’ was Weygand’s reply.

He had chosen the right man for a near-impossible job. In 1928, aged 44, de la Porte du Theil had grown bored with peace-time soldiering and since alternated between his chair at the War Academy and being a sort of Baden-Powell for the French Scout movement. Raised as the son of a forestry inspector, he was a great outdoorsman, first-rate hunter and good horseman. Two days later he was back in Weygand’s office, having acquired a small staff and core of NCOs, to explain his plan for dividing the unemployed conscripts of the Free Zone into regiment-sized formations of 2,000 and sending them into remote areas where they could perform useful work like logging, road-making and re-afforestation. In lieu of the obligatory military service traditional in France, each conscript on reaching the age of eighteen was to serve eight months of a healthy back-to-nature life, living under canvas until the work-teams had constructed themselves more permanent accommodation.

When Weygand told Pétain, the marshal thought it was a wonderful way of stiffening the moral fibre of the nation’s dissolute youth by removing them from the temptations of city life and inculcating a respect for manual labour and a sense of patriotic duty against the day when military conscription was resumed. On 30 July he announced the inauguration of the Chantiers de Jeunesse, or youth work camps, placed under the aegis of the Ministry of Youth and the Family, so that the Germans would not be alarmed by thinking it a clandestine army, although privately when appointing de la Porte du Theil Commissioner-General of the Chantiers, he said unequivocally, ‘Make me an army.’ Whatever the two men took that to mean at the time, it is unlikely that either foresaw the mission ending with the Commissioner-General’s arrest and deportation by the Germans, while his enemies accused him of supplying a ready-made source of manpower for the German compulsory labour programme, despite evidence that men from the Chantiers made up less than 2.4 per cent of forced workers, partly because they had learned self-reliance and were prepared to risk the alternatives.

This unknown general is very much a man of his time. To evaluate him is difficult today. Modelled on the army that he knew well, the Chantiers were organised in six regiments: five in the Free Zone and the other in French North Africa. In each, approximately 2,000 men were to be deployed on public works, divided into companies and platoons. To avoid military nomenclature, the largest units were called

groupements

and each was divided into ten

groupes

of 200 men each – roughly equal to a company – with each

groupe

divided into

équipes

or light platoons of fifteen men.

The first intake eventually numbered 87,000 conscripts issued green and khaki military-style uniforms, in which they served until February 1941. Their duties were decided by unit commanders, with the proviso that they be kept busy! The day began with a salute to the colours, followed by a pep talk and the morning devoted to work, with the afternoon for physical training and technical instruction. In practice, the unwilling conscripts found pay of 1 franc and 50 centimes per day and campfire singsongs in the evening a poor compensation for money in their pockets, girls, bars and billiard halls. They made this plain by stealing, fighting, drinking when they could and sabotaging state property most of the time. The propaganda posters likening them in battledress and beret to the warlike ancient Gauls were treated with due derision, and they showed little enthusiasm for planting trees, making roads and digging ditches under quasi-military discipline. In the Occupied Zone, young men were offered a different adventure: to go and work in the Reich. Figures are unreliable, but between 40,000 and 72,000 volunteered and joined the 1.5 million foreign workers already replacing German manpower in factories and on farms.

On 6 July all foreigners’ visas were cancelled and non-residents were made subject to travel restrictions. That month, acts of open hostility to the occupation forces were swiftly punished to serve as lessons to the general population. In Rouen, Épinal and Royenne lone protesters cut German telephone lines and were executed by firing squad. The only violence in Bordeaux came when a distraught Polish refugee shook his fist at a military band, for which he too was shot on 27 August.

By then, Baboushka’s family had filled their villa with refugees to avoid it being requisitioned when the first German troops, watched by silent crowds wondering what was going to happen next. Renée and her mother told the children not to look at the Germans, but just pretend they were not there. It was all rather English. François Mauriac put it more poetically. ‘Have eyes that see nothing,’ he advised his compatriots. However, it was very hard for a Frenchwoman not to thank a polite, smiling soldier who lifted her heavy suitcase onto a train, as it was for Renée to refuse a seat on a bus when a German politely stood up for her.

The empty de Rothschild villa next door to the de Monbrisons’ was requisitioned for a German general and his staff. Renée’s sons were fascinated by the two armed sentries goose-stepping at the bottom of their driveway, day and night. A thirsty sentry who asked them to sneak him a bottle of lemonade from a nearby shop rewarded the boys with cigarettes. When their mother found out, they were sent to bed without supper.

They watched an anti-submarine net being strung from the beach below their villa to Cap Ferret on the far side of the entrance to Arcachon lagoon. Thus protected, the Wehrmacht rehearsed Fall Seelöwe or Operation Sealion, its planned landing in Britain. Soldiers were pushed overboard from landing barges to test how well they could swim with full pack and weapons and trucks were driven ashore towing a dozen bicycle-soldiers on a rope, most of whom fell off in the soft sand. Forbidden to have anything to do with the unwelcome neighbours, the boys took a dangerous pleasure in hiding by the roadside and pelting the last trucks of German convoys with pine cones.

6

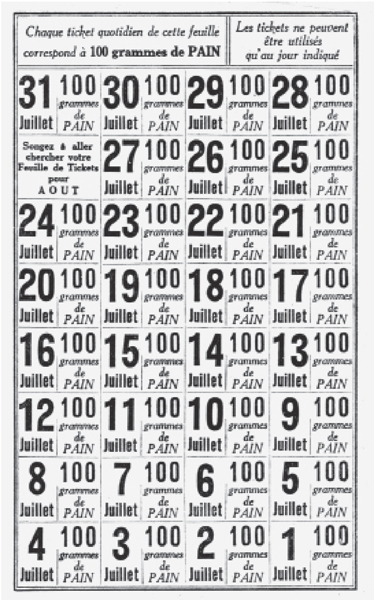

Motor fuel becoming unobtainable for civilians, bicycles came into their own. Like many others, Renée rarely went out without a trailer tied behind her bike – not that there was very much to buy, apart from locally caught fish, artichokes, root vegetables and horse meat once a month. Bread rationing was already in force. Coupons for 100g per person were usable only on the date printed on them, to prevent stockpiling.

People spent hours every day in the long queues outside the few bakeries and food stores still open. The problem at this early date was not so much shortage of food as disruption to food production and distribution caused by 8 million refugees being far from home, butchers, bakers and other shopkeepers among them. In many areas under no military threat, the population had been

ordered

to leave their homes, taking only three day’s provisions with them. In their deserted villages and towns it was often the German army that replaced the French infrastructure by setting up a soup kitchen or by distributing bread for stay-at-homes and returnees. German railwaymen were already driving trains that enabled some refugees to return home. On the bandstands in public parks, Wehrmacht musicians played afternoon concerts to calm the population. On the hoardings, the tattered general mobilisation notices from the previous September and later posters warning of a mythical fifth column stabbing the army in the back were swiftly covered by new ones showing a valiant Wehrmacht soldier holding a grateful small child in his arms above the message: ‘Abandoned by your leaders, put your trust in the German soldier!’

7

That there were rapes and some armed robberies was inevitable with over a million armed men in areas populated by old men, women and children. In some places, soldiers in German uniform demanded food and drink at the point of a gun when their own supplies had run out, but this tended to occur in the country and small villages. In the towns policed by the

Feldgendarmerie

they were on their best behaviour and insisted on paying for what they wanted. True, they used German money, but from 20 June onwards that was declared legal tender at the very favourable rate of exchange imposed by Berlin: one Reichsmark equalled 20 francs. Indeed, the Wehrmacht was mostly so well behaved that many bewildered French refugees wondered why they had been ordered by the authorities to flee their distant homes.

A rigid curfew was imposed from 10 p.m. to 5 a.m. – the start being put back on 7 July to 11 p.m. and midnight in November as a reward for the population’s good behaviour. It was decreed that householders were now responsible for cleaning the space in front of their houses, as in Germany. Similarly, peasants must clear weeds and tidy up their farms. Clocks must be put forward an hour, to Berlin time. The French

tricolore

flag must be removed from town halls and war memorials. The first wave of German orders seemed a small price to pay for the end of the bloodshed to a population fed up with the vacillations and ineptitude of their own authorities and elected representatives. And Marshal Pétain was the hero of the hour, for it was he who had achieved this miracle.